By John Helmer, Moscow

No ambition in Russia runs wider and higher than that of Igor Sechin, 58, chief executive of Rosneft.

To help fill the Venezuelan treasury, deter attacks on President Nicolas Maduro, reinforce his army, and show the world he’s the Russian who can defeat both types of war the US is waging against the world – sanctions war and regime-change war – no bill would be too expensive for Sechin to pay. And if he can do that, he will show that he’s the natural successor of President Vladimir Putin. In point of cost for Rosneft, the Venezuelan strategy is relatively cheap.

For the Russian military, who have created the most powerful army in South America (also a match for Canada ), with a decade of deliveries of air and ground weapons, the Venezuelan front is a fresh tester of American warmaking at low money cost and little risk of Russian casualties. The combination of Sechin and the Russian General Staff to defend Venezuela is a potent weapon to demonstrate to the world that US threats are bluff.

So, win or lose on the battleground of Venezuela, at home Sechin is showing his Russian allies that he’s their winner in the presidential power contest ahead.

Not everyone agrees. “Yes, the presidency is a matter of Sechin’s ambition; it’s also a condition for his survival,” comments a source who has known Sechin well. “As to who his allies are, I am not able to tell because he has managed to come into conflict with everyone around Putin. But if Sechin becomes the Kremlin’s lead on Venezuela, then Sechin will lose his battle for the Kremlin.”

In wartime it can’t be expected that Venezuela and Russia are going to reveal publicly the balance-sheet of the debts between Caracas and Moscow; certainly not how the two plan to evade the sanctions imposed on arms deliveries, introduced by the European Union in November 2017, or the US sanctions and asset seizures which the US (and the Bank of England) introduced on January 28, 2019.

The Russian Finance Ministry refuses to say exactly how much Venezuela currently owes Russia. However, on January 29, Deputy Finance Minister Sergei Storchak (right) confirmed that semi-annual interest payments of $100 million on sovereign debt of $3.15  billion were agreed in November 2017, and are continuing; repayment of the principal is postponed until 2023. “We have payments due in September [30] and March [30]. There are no overdue amounts. The last time the amount [paid] was more than $100 million; the upcoming payment, the same. We have a fixed interest rate. When the loan repayment period begins [in 2023], along with interest, part of the debt is extinguished, this is a classic scheme of repayment of the state debt.” Storchak conceded that following the escalation of US sanctions last month, “there will probably be problems. Everything now depends on the army, on the servicemen, how true they will be to their duty and oath. Another assessment is difficult to give — impossible.”

billion were agreed in November 2017, and are continuing; repayment of the principal is postponed until 2023. “We have payments due in September [30] and March [30]. There are no overdue amounts. The last time the amount [paid] was more than $100 million; the upcoming payment, the same. We have a fixed interest rate. When the loan repayment period begins [in 2023], along with interest, part of the debt is extinguished, this is a classic scheme of repayment of the state debt.” Storchak conceded that following the escalation of US sanctions last month, “there will probably be problems. Everything now depends on the army, on the servicemen, how true they will be to their duty and oath. Another assessment is difficult to give — impossible.”

Russian reporters have been claiming that Venezuelan debts to Russia currently total $17 billion. This is guesswork; it started last year in reports by the Reuters news agency in Caracas. The officially agreed numbers comprise the debt between Rosneft and Venezuela’s state oil company group, Petroleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA) of about $5 billion; about $4 billion owed for Russian arms deliveries; $1.5 billion in loan collateral which Rosneft holds in CITGO, the US refinery and retail gasoline subsidiary of PDVSA; and $5.8 billion in obligations which the Maduro Government began negotiating with the Paris Club of government creditors starting last June. These numbers don’t add up to $17 billion, and the Paris Club number isn’t broken down by creditor country claims. It’s known that the Paris Club aggregate includes $263 million owed to Brazil. How much of the balance — $5.573 billion — is owed to Russia and to China is not reported by the Paris Club. Nor are details of the off-budget financing of some Russian arms deliveries which may make the debt to Russia larger.

Rosneft was asked to clarify how much money it has paid out in loans to the PDVSA group, investments in joint oilfield development projects, and cash advances for future deliveries of Venezuelan oil. The company refuses to answer.

Rosneft CEO Igor Sechin (left) presents a sword to President Nicolas Maduro (right) in Caracas on July 26, 2016.

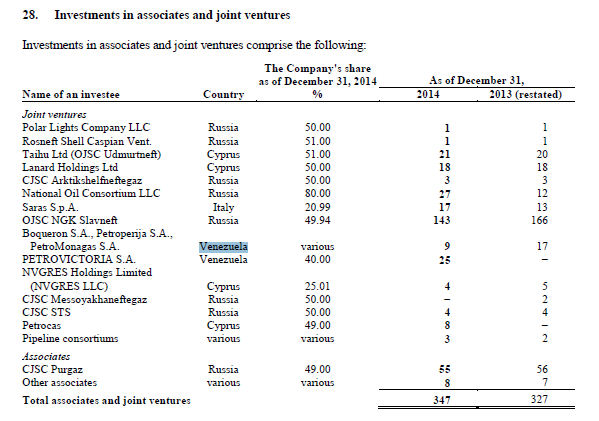

The published financial reports of Rosneft tell part of the story. Beginning in 2014 Rosneft reported it had taken over oilfield projects in Venezuela from TNK-BP, when the latter was acquired by Rosneft in 2013. The Venezuelan subsidiaries are shown in the 2014 report of Rosneft’s subsidiaries and project investments.

“As a result of the TNK-BP acquisition… the Company obtained equity interests in certain assets in Venezuela. The most significant of these investments is in PetroMonagas S.A. in which the Company holds a 16.7% interest. The investment in Venezuela of RUB 17 billion [in 2013, equivalent to $515 million; in 2014 $304 million] is accounted for as an investment in joint venture using the equity method. PetroMonagas S.A. is engaged in the exploration and development of oil and gas fields in the eastern part of Orinoko Basin. In 2014 PetroMonagas S.A. produced 53.4 million barrels of oil equivalent. PetroMonagas S.A. is an integrated project involving the extra-heavy crude oil extraction and the upgrading, production and export of synthetic crude oil.”

“On May 23, 2013 the Company entered into a joint venture agreement with Corporacion Venezolana del Petroleo, a subsidiary of Petróleos de Venezuela S.A. (“PDVSA”), Venezuelan state oil company. On November 14, 2013 the Petrovictoria S.A. joint venture was incorporated to effect the exploration of heavy oil of Project Carabobo-2 in Venezuela. On August 27, 2014 the Company paid a 40% of bonus in the amount of $440 million (RUB 16 billion at the CBR official exchange rate at the transaction date) for participation in Petrovictoria S.A. as a minority partner.”

In addition, Rosneft reported that it had increased its stake in the National Oil Consortium LLC (NOC) to 80%; NOC “provides financing for the exploration project at Junin-6 block in Venezuela jointly with a subsidiary of PDVSA”.

By the end of 2014, Rosneft reported adding another Rb34 billion ($696 million) to its investment in PetroMonagas and Petrovictoria.

Source: https://www.rosneft.com/

In May 2016 Rosneft reported that it had “increased its stake in the Petromonagas joint venture with the state oil company of Venezuela Petróleos de Venezuela SA… from 16.7% to 40%. The share of PDVSA was reduced to 60%. The cost of the additional share acquisition was US$ 500 million (RUB 33 billion at the CBR official exchange rate at the date of the transaction).”

These investments were reported to be generating profit dividends in the years following – Rb8 billion ($138 million) in 2017; Rb19 billion ($302 million) in 2018. Subtracting the reported profits of $440 million from the reported cost of investments since 2014 indicates a net investment by Rosneft in its PDVSA ventures of a little less than $1 billion.

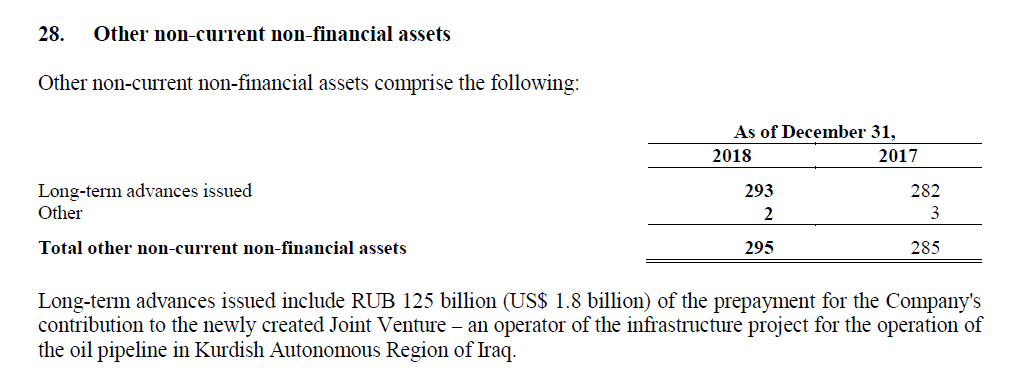

Cash advances by Rosneft for oil deliveries by PDVSA started in 2016. That year they amounted to Rb83 billion ($1.4 billion). In 2017 the advances jumped more than threefold to Rb282 billion ($4.9 billion). Last year Rosneft says it advanced a total of Rb293 billion ($4.7 billion), but only $2.7 billion of that sum went to PDVSA. The aggregate comes to the equivalent of $9 billion.

Source: https://www.rosneft.com/

Rosneft discloses little of its exposure to Venezuela in the latest financial report for 2018.

“The Company continuously monitors projects in Venezuela realized with its participation. Commercial relations with the Venezuelan state oil company PDVSA are carried out on the basis of existing contracts and in accordance with applicable international and local legislation.”

What is missing from the accounts is how much oil PDVSA has shipped in repayment of the advances, and what the pricing of this oil has been in relation to the international trade price, and in relation to PDVSA’s cost of production. It isn’t known, for example, if Rosneft has been making a profit on the PDVSA delivery price, and PDVSA a loss, or vice versa. Also, it is uncertain what the debt balance was that PDVSA owed to Rosneft at the end of each of the last three years, or now. When questions like this were asked early this month by investment analysts at Rosneft’s presentation of its 2018 financials, it was claimed that PDVSA has repaid $2.3 billion. This suggests an outstanding debt to Rosneft at the moment of $6.7 billion.

Here is the current list of 28 analysts accredited by Rosneft to cover the company for the investment markets. Each one of them is frightened that if he or she issues information Sechin does not want published, he will pressure their employers to sack them. None will agree to say what they calculate to be the current net value of Rosneft’s exposure to PDVSA.

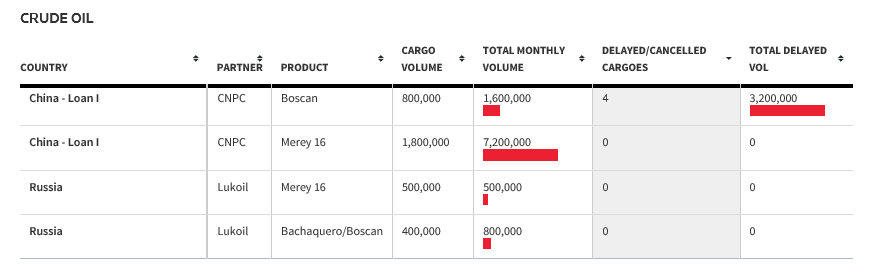

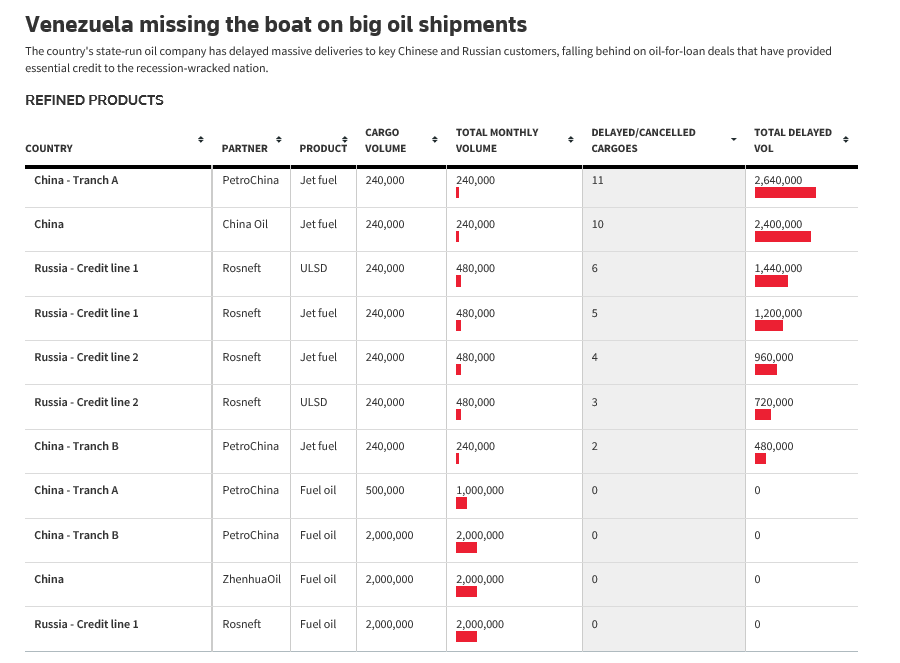

There is speculative reporting by Reuters and the oil media on how much Rosneft has been earning from the PDVSA shipments delivered to US and Indian refineries, and by how much PDVSA has been slowing down deliveries in order to keep more cash from its oil sales to cover the state’s import requirements and domestic budget obligations. Similar production problems and delays in deliveries for repayment of the cash advances have been reported by Chinese oil companies.

In these two tabulations, Reuters estimated the volume of delayed deliveries between Venezuela and Russia, Venezuela and China as of February 9, two years ago. The news agency claimed its source then was “internal company documents reviewed by Reuters”. In time PDVSA, Rosneft and the Chinese staunched these leaks, but now there is nothing current and credible from any source.

CLICK ON IMAGE TO ENLARGE

Source: http://fingfx.thomsonreuters.com/

Last November, two Caracas-based reporters for Reuters claimed to have anonymous sources for a story that Sechin had met secretly with Maduro to complain that PDVSA was shipping more of its pre-paid oil to Chinese companies than to Rosneft. “According to Reuters calculations based on PDVSA data, the Caracas-based group “delivered around 463,500 bpd [ barrels per day] to Chinese firms between January and August, a roughly 60 percent compliance rate. That compares with around 176,680 bpd to Russian entities, or a 40 percent compliance rate.” There is no telling if this is true. During November of 2018 Rosneft reported that Sechin visited Beijing, but not Caracas.

Russian press reporting last week indicated that an early impact of US sanctions against PDVSA has been to stimulate the market price of the types of heavy (high-sulphur) crude which PDVSA produces at its Venezuelan oilfields. Because of the added refining cost of removing sulphur from this oil, it has usually been priced at a discount to the lighter, lower-sulphur Brent blend of crude oil moving in and out of Europe. This has meant the Sokol, ESPO and Urals blends which Rosneft produces and exports are usually cheaper than Brent. However, in the weeks since the US commenced its attack on PDVSA, threatening shortages of this type of oil worldwide, the market prices of Sokol and ESPO have shot up; they are currently above the Brent price of $66.25.

CLICK ON IMAGE TO ENLARGE

Source: https://oilprice.com/ Sokol crude is produced by the Sakhalin-1 project in the Russian Fareast; it is a light crude with an API gravity of 36.0° and 0.30% sulphur content; API stands for American Petroleum Institute; its measure of gravity compares the density of oil to water. The East Siberia-Pacific Ocean (ESPO) pipeline delivers overland to China and at the Pacific port of Kozmino a blend with an average API gravity of 35.6° and 0.48% sulphur content. By contrast, Brent has an API of 38.06° and sulphur content of 0.37%. The question of what export price for Venezuelan crude oil represents break-even draws controversy, depending on how break-even is calculated in relation to the cost of extraction and refining; and the value of oil taxes to the state budget surplus or deficit. Eric Zuesse makes the case that Venezuelan oil cannot rise above break-even at current market pricing; click to read. For the break-even point of the international oil price in order for the Russian state budget to run a surplus, read this.

The US-backed opposition in Caracas has attacked Rosneft; the Reuters bureau in Caracas has amplified their claims. “Rosneft is definitely taking advantage of the situation,” reported Reuters, quoting Elias Matta, vice president of the energy commission at Venezuela’s elected National Assembly. “They know this is a weak government; that it’s desperate for cash – and they’re sharks.” Masking a US Embassy source, Reuters added: “Rosneft is making the opposite play – using Venezuela’s hard times as a buying opportunity for oil assets with potentially high long-term value. ‘The Russians are catching Venezuela at rock bottom,’ said one Western diplomat who has worked on issues involving Venezuela’s oil industry in recent years.”

Until recently, the career rise of Sechin, a native of St. Petersburg, has had next to nothing to do with the Defense Ministry or the General Staff; the Venezuelan conflict with the US is the first to draw him into military policymaking. Asked what relationship he has cultivated with Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu or General Staff chief Valery Gerasimov, a source from St. Petersburg responded sceptically. Shoigu, he said, is a weak figure, and “the whole ministry is supervised by the FSB. So I don’t think Sechin has bothered to build any kind of relationship with the Ministry and the generals. There are too many of them and they are replaceable.”

Sechin’s first deal with Venezuela was announced in 2012 with President Hugo Chavez, but he had been prominent in the talks in the Kremlin in October 2010, when Chavez and then-President Dmitry Medvedev signed an action plan for the period, 2010 to 2014. This set out “cooperation priorities in politics, economic and financial relations, energy, military technical cooperation, nuclear energy, telecommunications, agriculture, fisheries, transport, healthcare, tourism, sports, culture, and disaster relief. “

President Dmitry Medvedev (2nd from left) and Igor Sechin (3rd from left) meet President Hugo Chavez (3rd from right) at the Kremlin, October 15, 2010. Source: http://en.kremlin.ru/

Missing from this list was defence, security and military cooperation. Four years earlier, in July 2006, Russian arms deliveries had commenced with an order for Kalashnikov rifles; they accelerated quickly to include 24 Sukhoi-30 fighters and 53 attack helicopters.

At first, US military analysts thought the Russian effort to sell arms was just as commercial in motive as the investments in oil and gas exploration. “Russia’s return to Latin America was boosted by its economic and political recovery over the years 2000-2008, which validated [former Prime Minister Yevgeny] Primakov’s idea of a multipolar world. In addition, it should be noted that, in contrast to Chinese activities in Latin America, Russia’s engagement is focused on a limited number of countries and economic sectors—such as oil exploration, mining, some technology sectors, and the purchase of food products. In light of this, the evidence does not seem to support the idea that Russia is encroaching on the United States’ historical influence zone, but instead points to the way Latin America and the Caribbean are forging new opportunities for international cooperation with countries other than the United States.”

In Moscow on December 6, 2018, left to right, Chief of the Russian General Staff, General Valery Gerasimov; Venezuelan Defense Minister Vladimir Padrino Lopez, and Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu.

Military analysts in Moscow refuse to discuss how Russian strategy towards Venezuela has changed since Chavez died in 2013 and Maduro succeeded him. A Washington Post assessment of last December quoted Moses Naim, an ex-trade minister before Chavez’s time and a US-based journalist, as saying the inability of Venezuela to service its Russian arms debt encouraged Sechin to expand into energy sector investment and oil trading. “After the first stage, [Naim] said, when Venezuela was among the ‘best clients of the Russian arms industry,’ Russia found it was getting harder to collect on debts owed by Caracas, and the purchases turned into loans. ‘That changed the main actors in the relationship,’ Naím said in an interview. ‘It was no longer the Russian arms salesmen and warlords but the financiers.’ As Venezuela struggled to manage its debt, IOUs were gradually converted to bonds and other instruments that could be used to acquire state assets.”

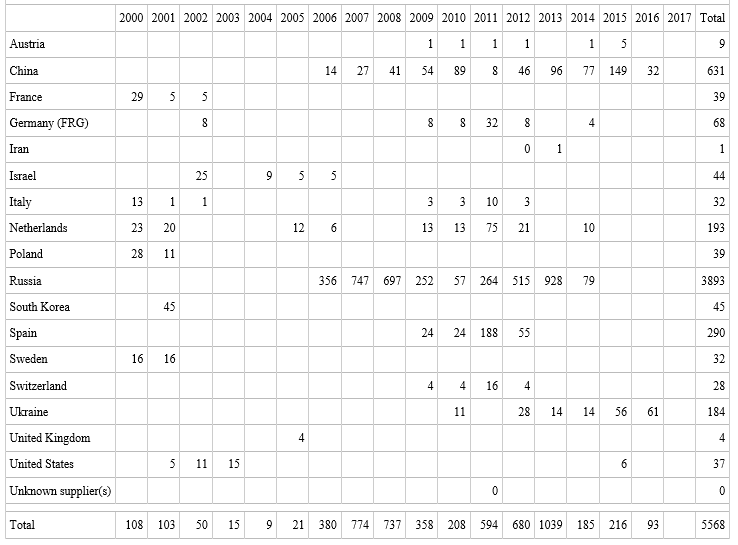

Naim is wrong, at least through 2010. Data collected by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) indicate that Russian arms deliveries to Venezuela started in 2006, doubled in value in 2007 and 2008, and peaked in 2013. Altogether, according to SIPRI, the value of Venezuela’s arms purchases from Russia totalled $3.9 billion to the end of 2017.

The European Union embargo which began in November of that year stopped new contracts from being signed by the EU states, but not ongoing contracts and deliveries of naval vessels; the embargo did not apply to Russia and China.

VENEZUELA’S IMPORTS OF ARMS, 2006-2017 BY VALUE & COUNTRY OF ORIGIN

(in millions of US dollars)

Source: http://armstrade.sipri.org/ Note that the total for Spain, the leading arms exporter to Venezuela from the EU, is significantly less than the total published by the EU.

By value, the most costly arms imports have been missiles and anti-aircraft systems, followed by tanks, armoured cars, and naval vessels.

TYPES OF MILITARY EQUIPMENT IMPORTED BY VENEZUELA, 2000-2017

(in millions of US dollars)

Source: http://armstrade.sipri.org/

SIPRI analysts have reported that because state budgets are not the only source of money to pay for arms, the data in these tables may fall short for the biggest military spenders in South America, such as Chile, Peru and Venezuela, where income from natural resources such as oil, gas and copper has been used to directly finance a major share of weapons purchases.

“In the case of Venezuela…SIPRI’s military spending figures are drawn from official budgetary documents. Because a large proportion of arms purchases are funded through off-budget mechanisms, however, this data does not capture the full extent of the state’s military expenditure. Thus, although SIPRI’s current military expenditure data does not include off-budget funds, this does not mean that SIPRI was unaware of this form of financing. The main concern until now had been the lack of information and process transparency in these off-budget spending documents, which complicates efforts to create a consistent and reliable time-series for Venezuelan military expenditure. In many South American counties, such as Chile, Ecuador and Peru, and particularly Venezuela, the majority of off-budget funding comes from natural resources. In the case of Venezuela, its armed forces benefited tremendously from increased oil revenues. It has been reported that not only did the country’s official defence budget receive increases, but such revenues were also the main source of funding for off-budget weapon purchases.”

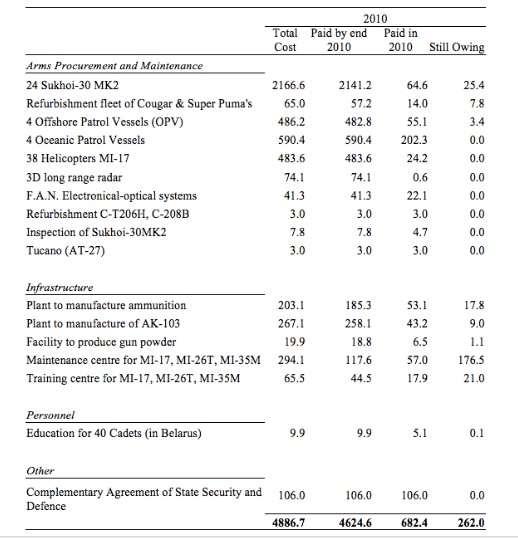

For Venezuela this also meant that before the oil price crash of 2014, growing oil revenues allowed for prompt repayment of arms imports. SIPRI has reported comparing the announced cost of Venezuela’s arms purchase with the announced repayments between 2006 and 2011. This table shows that by the end of 2010 Caracas had repaid Moscow $4.6 billion of the $4.9 billion bill for arms delivered by then; that was 95% of the contract amounts, with a balance owing of just $262 million.

VENEZUELAN ARMS IMPORTS FROM RUSSIA, COST AND PAYMENT BY END-2010

Source: https://www.sipri.org/ The total value of Russian imports in this table is more than $2 billion larger than the value of arms imports reported by SIPRI from the state budget figures.

From 2011 to 2017, as SIPRI’s tabulation of the official inter-government figures shows, Russia and Venezuela agreed on arms for a total of $1.8 billion, the most important of which were S-300 anti-aircraft missile systems. Adding this sum to the unpaid balance at the end of 2010 indicates a figure of $2.1 billion. However, the state debt owing when the two governments agreed in November 2017 on a five-year rescheduling of payments came to $3.15 billion. The difference suggests that between 2015 and 2017 Maduro requested, and Putin agreed to deliver another $1 billion in military goods.

No new arms contracts or deliveries have been announced by either Russia or Venezuela since 2017. Russian press reporting has identified only shipments of spare parts, maintenance of weapons already delivered, troop training, command-and-control testing, and construction of a much delayed factory for production of Kalashnikov rifles. There has been no major new arms contract since the domestic opposition to Maduro escalated, but Russian military planning has intensified to deter and counter the expected lines of US attack.

Early this month there have been reports that Maduro has requested, and the Kremlin is considering, new missile defence systems against ground attack, including rocket launchers of the Smerch type. These are described as battlefield artillery with a “lethal footprint of… about 70 hectares, and firing range varies from 20 and 90 km. According to experts, the volleys of six Smerch units launching simultaneously is comparable in destructive power to that from a tactical nuclear explosion.”

A unit of the BM-30 Smerch rocket launcher in Venezuela. For background, click to read. First orders and deliveries of this weapon were reported by US and British sources in 2012.

Last week, the Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov responded: “I will leave this without comment.”

The Kremlin has announced the last direct contact between President Putin and President Maduro was a telephone call on January 24. Putin, according to the published communiqué, “expressed support for the legitimate Venezuelan authorities amid the worsening of the internal political crisis provoked from outside the country. He emphasised that destructive external interference is a gross violation of the fundamental norms of international law. He spoke in favour of searching for solutions within the constitutional framework and overcoming differences in Venezuelan society through peaceful dialogue.”

Putin and Maduro reportedly also agreed “to continue Russian-Venezuelan cooperation in a variety of areas.”

A review of Venezuela’s capability to combat a ground attack by US-backed ground forces from Colombia and direct US air and missile attacks was published on January 29 by Andrei Kotz. “The most powerful side of the Venezuelan Armed Forces”, he reported, “is considered to be a deeply layered system of air defence. It is air defense that acts as a deterrent and can seriously cool the ‘hot heads’ among the supporters of a military invasion. Organizationally, the air defence of the country consists of five ranks. Long-range anti-aircraft missile systems are represented by two divisions of S-300VM (a total of eight batteries, each with three or four launchers). This SAM allows you to effectively deal with aerodynamic targets at distances up to 250 kilometres and at altitudes from 25 metres to 30 kilometres. Its advantages include radar with phased array antenna; good protection from electronic warfare measures; a high degree of automation. According to the developer, the S-300VM is effective against stealth aircraft and is even capable of hitting ballistic targets.” Kotz elaborates on the shorter-range and low-altitude BUK and Pechora missile systems now installed in Venezuela which have proved in Syria their capability to counter cruise missiles fired by the US.

The Pechora 2M missile at a Venezuelan military parade in 2012. The missile is for close-in defence against aircraft and cruise missiles.

An analysis of Russian military thinking on the Venezuelan war front appeared on February 12 by Yevgeny Krutikov, a reporter who has served as a military intelligence (GRU) field officer in the Balkans. In this assessment, the US priority is to avoid a direct military clash with the Russian weapons by inducing the Venezuelan officer corps to defect and by demoralizing the troops. “Speculation about a possible military solution to the Maduro government on the part of the United States is mostly psychological. The generals have clearly spoken in favour of the legitimate government, and attempts to persuade the lower-ranking officers to their side have not yet had an effect. But there is a danger of direct US military intervention, with the help of neighbouring countries Colombia and Brazil. The cover-story for this may be the situation around the so–called humanitarian [aid] convoy, frozen in anticipation at the Colombian border facing Cúcuta, another historically important Venezuelan city located right at the frontier. It also houses the largest base of the Venezuelan army, which Maduro visited as one of the first in preparation for the [current military] exercises.”

Guardian video from the Colombian side of the border at Cúcuta on February 7. On the Venezuelan side of the frontier, the highway is blocked.

Russian Foreign Ministry spokesman Maria Zakharova dismisses the convoy as a tactic to justify military intervention. “We know what goals the Americans are pursuing in handing out their cookies,” Zakharova commented on February 14. “We categorically object to any attempts to politicise the issue of humanitarian aid to Venezuela and to use it to cover up the manipulation of public opinion and to mobilise anti-government forces for a coup… The Red Cross openly announced that the planned action has nothing in common with humanitarian aid and publicly distanced itself from participation in this more than dubious project. It has refused to take part in what it does not consider humanitarian aid.”

In the GRU assessment, the US military attack on Venezuela may follow either the “Iraqi” or the “Yugoslav” scenarios. In the first, “when a part of the Venezuelan Army can stand on the side of the ‘aggressor’, and internal clashes in the country can be interpreted in the media space as the power actions of the ‘bad dictator’ against the ‘freedom advocates’. In such a case, a ground invasion by Colombia could follow against the background of unfolding stories of the ‘humanitarian crisis’ in Venezuela and of assistance to the ‘suffering people’. This is how reports from Kosovo about ‘hundreds of thousands’ of Albanian refugees were used. Direct support for such an invasion should be provided by the Colombian Army, which is completely dependent on the United States.”

The second American scenario, as judged from Moscow, is the Yugoslav war option. “The US Army, using its virtually unlimited resources of strategic aviation and cruise missiles, [would] suppress the resistance of the remaining loyal Maduro parts of the Venezuelan army, its headquarters and warehouses, thereby bringing discord into the psychological state of the army. The purpose of such an attack would not be so much to cause irreparable damage to Venezuela’s infrastructure, as it did in Yugoslavia, but rather to reduce the psychological readiness of the Venezuelan army and militia to resist the forces of invasion and internal reaction. A massive missile and bomb attack on the staffs and loyal units of the Venezuelan army should lead to a sharp drop in the psychology of resistance and emotional collapse.”

“Of course, South America is not Yugoslavia.”

Leave a Reply