By John Helmer, Moscow

In the programme for the special form of Russian governance which Vladislav Surkov (lead image, right*) calls Putinism for the next hundred years, there is no power-sharing with businessmen (oligarchs or merchants), social classes, intelligentsia, the Russian Orthodox Church, political parties, parliaments, the Constitution or the civil and criminal courts. Rule will be by the military, the security services, and the state corporations advising the supreme leader. He in turn will be trusted by Russian people to convey their wishes, settle disputes, balance rights from wrongs, and check the state from corruption. Mostly, he will be trusted to listen.

To those whom Surkov, a Kremlin adviser since 1999, removes from power, in order to make Russia combat-ready against the US and the NATO alliance, this is a revolutionary manifesto.

“In the new system,” Surkov wrote in a Moscow newspaper last week, “all institutions are subordinated to the main task – trusting communication and interaction of the Supreme ruler with citizens. The various branches of government converge on the identity of the leader, considering their value not in itself, but only to the extent that they provide a connection with him. Besides them, informal ways of communication work at bypassing formal structures and elite groups. But when stupidity, backwardness or corruption interfere in the lines of communication with people, energetic measures are taken to restore audibility.”

Nezavisimaya Gazeta, February 11, 2019: “Vladimir Surkov: The long-lasting state of Putin: About what, in general, is happening here”

“Putinism as the ideology of the future”, Surkov declares. It’s already, and will continue to be, “a new type of state” for Russia. In Surkov’s version of the historical precedents, those he ignores are as telling as those he includes. There’s no Ivan the Terrible; no tsar after Peter the Great; no woman like the Empress Catherine; not even Joseph Stalin leading the fight against the German invasion.

Putinism is the successor of Leninism, Surkov believes, although “the real Putin is hardly a Putinist, just as Marx was not a Marxist, and we can’t be sure he would have agreed to be one had he found out what that’s like.” The new Russian system of state power Surkov is pitching can do without both of them. This, he concedes, “looks, of course, not particularly elegant, but more honest…suitable not only for the domestic future, but also with significant export potential — the demand for it or for its individual components already exists; its experience is studied and partially adopted, it is imitated by both the ruling and opposition groups in many countries.”

This is Surkov’s job application for the time when he intimates the Kremlin must be staffed by Russians capable of fighting Americans. Naturally, those sore at the prospect of losing their power, influence, and money are angry. To them, Surkov is, in the words of Alexei Venediktov, the pro-American director of Radio Ekho Moskvy, a fascist of 1930s vintage. “Proto-fascism in watercolours”, comments Gleb Pavlovsky, a political tactician who was once on the Kremlin payroll, but no longer.

Surkov’s manifesto can be read here in the Russian; and here in an English translation.

By exclusion, Surkov reveals who is losing in the contest for the presidential succession. “Businessmen, who consider military pursuits to be of lesser status than commercial ones, have never ruled Russia (almost never; the exceptions were a few months in 1917 and a few years in the 1990s). Neither have liberals (the fellow travelers of businessmen) whose doctrine is based on the negation of anything the least bit police-like. Thus, there was nobody in charge who would curtain off the truth with illusions, bashfully shoving into the background and obscuring as much as possible the main prerogative of any government—to be a weapon of defence and attack.”

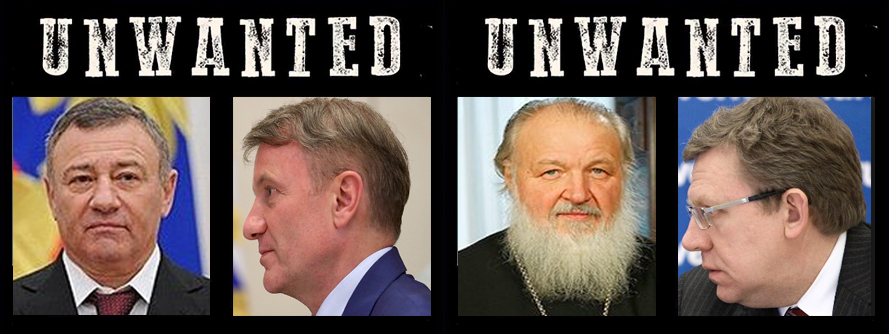

Left to right: sanctioned oligarch Arkady Rotenberg; German Gref, Chief Executive of Sberbank; Patriarch Kirill (Vladimir Gundyayev); Alexei Kudrin, Accounting Chamber Chairman and pro-American candidate for the presidency. Days before Surkov’s piece appeared in Nezavisimaya Gazeta, Gref gave a lengthy press interview in which he set out his view of the future; it is the opposite of Surkov’s. Gref concludes with an imprecation. “Russia is governed directly by the Lord God, otherwise it is impossible to understand how Russia still exists.” Gref’s God may not be a Christian one, if his patronage of the Indian Sadhguru is anything to go by; for details of Sberbank’s connection to God, click to watch. For more on the contrast between Gref and Surkov, click to read.

Defence from whom by whom?

Surkov’s enemy is the US; his Russian model is the Stavka – the combination of the General Staff and the security ministries under the commander-in-chief. “The need to control huge, heterogeneous geographic areas, and constant participation in the thick of geopolitical struggle make the military and policing functions of the government the most important and decisive. In keeping with[Russian] tradition, they are not hidden but, quite the opposite, demonstrated…There is no deep state in Russia—all of it is on display.”

If there will be no Russian resistance, Surkov warns, Russians are doomed to be casualties and victims. “Who are we in the worldwide web – spiders or flies?”

Surkov is the first Kremlin official to attack Putin’s alliance with Patriarch Kirill in reviving the 19th century doctrine, Orthodoxy, Autocracy, Nationality. They are ideologists for passivity and defeat, Surkov responds — who claim that power in Russia is “the executor of God’s will.” The only ideological precursors he names – de Gaulle, Ataturk, Marx, Lenin – were determinedly secular; three of them famously anti-Christian.

“It would be an oversimplification to reduce this theme to the often-cited ‘faith in the good tsar’. The deep [Russian] nation is not the least bit naïve and definitely does not consider soft-heartedness as a positive trait in a tsar. Closer to the truth is that it thinks of a good leader the same way as Einstein thought of God: ingenious but not malicious.”

Subordinating Kirill to Einstein is radical talk from a Kremlin apparatchik. If meant for Putin’s ears, it requires the President to change the way his mouth moves. Moscow press reporting of Kremlin rumours suggests that Anton Vaino, chief of the president’s staff, didn’t know of Surkov’s plan to publish, and didn’t approve the article in advance. Head of media for the presidential administration, Alexei Gromov, did know and approved, it’s claimed. So, too, the deputy chief of staff, Sergei Kirienko.

Left to right: Anton Vaino; Alexei Gromov; Sergei Kirienko.

Putin’s spokesman, Dmitry Peskov, told reporters that Putin is “prioritizing preparations for [his address] to the Federal Assembly. This is exactly what he has been doing.” Peskov claimed Putin knew about the article, but didn’t know if he had read it. “Surkov has experience in domestic politics, in party politics and in state-building that is hard to overestimate,” the spokesman added in endorsement.

Surkov is not addressing those who make their living on US Government or NATO stipends. They in turn have misheard and misunderstood what Surkov is saying. “Kremlin Puppet Master Surkov Distracts Public with Putin Panegyric” is the headline from a British academic. “To the system insiders around him,” claims another British think-tanker, “Surkov’s peers and superiors, the people who have much to gain but potentially all to lose from change, the message is that they too need not worry.”

Among Russians, no one has counted how many of Putin’s constituencies Surkov is proposing to liquidate. A former Moscow newspaper editor, now a Bloomberg writer in Germany, sees complacency in the status quo – “nothing needs to change and no new ideas are necessary…” The US-based Orthodox zealot Anatoly Karlin resents Surkov stripping the Church of its power. “Without Orthodoxy, what can autocracy plus…nationality, with no higher ethical superstructure, be other than your typical tin pot populist regime?…The problem with Surkov is that he evidently fancies himself to be a very clever, sophisticated…philosopher whereas in reality he is quite mediocre.”

Radio Ekho Moskvy is a well-known megaphone for critics of Putin and for opposition to the Stavka. The radio has been running almost daily broadcasts attacking Surkov. According to one of the commentators, Vladimir Kornienko, “the independent Surkov in an independent newspaper wrote an independent text on which nothing depends…” According to Abbas Gallyamov, a former Kremlin speechwriter, “the very fact that it is being discussed speaks of the colossal ideological vacuum that has arisen in society, in Russian politics. It is obvious that it sorely lacks some great sense.”

The radio’s correspondent in the US, Karina Orlova, has taken to a virulently anti-Russian publication, The American Interest, to report that Surkov’s piece “give[s] us a glimpse of the sorry state of intellectualism in Russia today”. She means to exclude herself.

Orlova diagnoses Surkov’s essay as a symptom of his psychopathology as a courtier. “As Surkov’s then-boss Leonid Nevzlin [Mikhail Khodorkovsky’s partner at Menatep Bank] told me in an interview last year, Surkov didn’t know how to work with people. He could do it ‘either from the bottom, or from the top. . .he could either give orders to people, or look at them from the bottom and bootlick.’ Surkov left Menatep in 1996 to join Mikhail Fridman’s Alfa Bank and, subsequently, the [Yeltsin] Family, which he has been part of ever since. Maybe Surkov never learned his lessons from Leonid Nevzlin, and his essay simply reflects his longstanding talents as a fawner.”

Left: Karina Orlova claims she fled to the US for safety after she was threatened in Moscow in 2018. Right: Gleb Pavlovsky.

To Pavlovsky, Surkov means to be ironic; his publication is a false front. “Here you can find a few hidden sub-texts… For me it is clear that Vladislav Yurievich is himself ironic in relation to what he describes. Surkov tries to gently, imperceptibly criticize, but to criticize without looking like a critic, making all these passes in front of the nose of his reader – the first Putinist.”

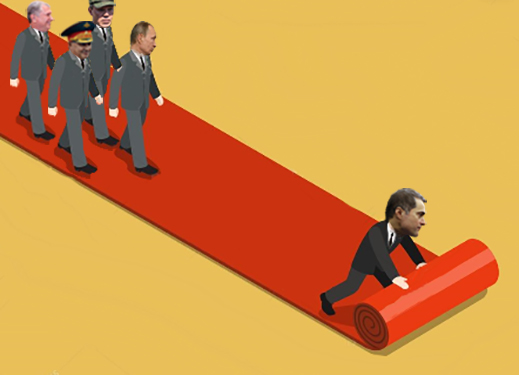

[* ] From left to right: Igor Sechin, chief executive of Rosneft; Sergei Shoigu, Defence Minister; Valery Gerasimov, Chief of the General Staff; Vladimir Putin; Vladislav Surkov.

Leave a Reply