By John Helmer, Moscow

United Company Rusal, the state aluminium monopoly run by Oleg Deripaska (lead image), has announced a third-quarter profit of $25 million, its first bottom-line in the black for three years. The company’s report explains the result by pointing to production cuts, the decline in costs of production, and a rise in the market price of aluminium.

In theory, the reason for the profit is that demand for Rusal metal is growing, and supply falling. “Healthy consumption growth,” Deripaska said on the company website last week, “coupled with production curtailments, have led to a deficit in the global market, ex-China, of 0.9 million tonnes of aluminium in the first nine months of the year. This, together with falling LME inventories, which have dropped below 4.5 million tonnes, means the deficit is continuing to widen. These positive market developments and our continued focus on cost controls and increasing margins through value added production have enabled UC RUSAL to report significantly improved third quarter results.”

In fact, Zug, London, and New York traders report, demand for physical metal is uncertain, especially inside China, while supply outside China is being restricted in warehouse by producers like Rusal, and traders allied with them. It remains more profitable to finance aluminium in storage than to sell to metal users and consumers. This is market manipulation, the traders say, pointing to Glencore, a minority shareholder in Rusal and Rusal’s principal trader. The fix isn’t stable and the revenue benefit for Rusal is neither certain nor predictable, the traders warn.

According to a London trade specialist, Rusal and Glencore are restricting the supply of metal out of warehouse storage by stretching the queue of buyers waiting to take delivery, and prolonging the time and cost of the warehousing. The extra buyers are paying to get aluminium out of warehouse is known as the premium, which must be added to the quoted London Metal Exchange (LME) price.

Between Rusal and Glencore, says the London trade source, “there is a participation split on premiums. I’d be surprised if it were 50:50.” The premium, and the secret division between Deripaska and Glencore’s chief executive Ivan Glasenberg (below left), have been the target of shareholder Victor Vekselberg’s (right) lawsuit at the London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA) between 2012 and 2014.

The LCIA settlement this past January, reported here, compensated Vekselberg for the way in which Deripaska and Glasenberg had kept the premium split out of shareholder hands. How much compensation was paid; what new premium split the shareholders have renegotiated since January; and how much premium income is now paid to Rusal’s account – there have been no answers to these questions from Rusal, Glencore, or the international banks which have been rolling over Rusal’s debts on assurances they know where the aluminium revenues are going. For more on the shareholder settlement, read this.

According to a London trade source, “producers like Rusal will tell you that metal leaving the LME is going to fill the supply-demand deficit in the market. That’s possible. But if it were all going straight to consumers, you’d expect some reaction in physical premium levels. Since these have simply continued rising, my inference is that little if any of the metal leaving the LME is going anywhere near a fabricator.”

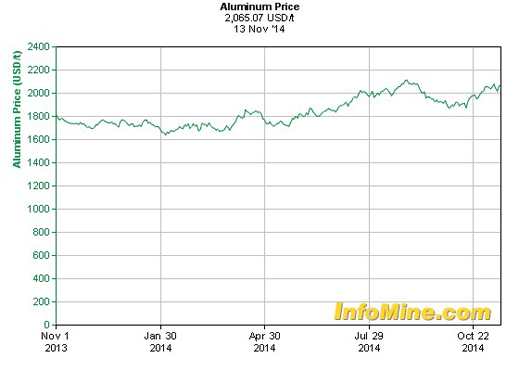

In its November 12 report, Rusal says the premium it received on the LME price for sales of its primary aluminium in the third quarter averaged $422 per tonne. That was up 55% over the same period of 2013. On sales of 904,000 tonnes, the premium revenues ought to have been $381.5 million. That’s 15.4% of Rusal’s declared revenue for the quarter of $2.5 billion. A year ago, premium revenue amounted to 11.2%. A year earlier, 9.2%.

Between the second and third quarters of this year, Rusal reports, the LME spot price grew by 10.5% to $1,798 per tonne. But at the same time the premium grew much faster – by 19.2%. The difference between the attributable premium revenue in the September quarter ($381.5 million) and in the June quarter ($316.1 million) is $65.4 million. If the premium had not moved as fast or as high, the profit would not have materialized — Rusal would stay in the red.

Source: http://www.infomine.com

Sources report from inside Rusal that “everything is fine — the current sentiments and expectations are high.” Deripaska said last week in Beijing he expects the premium to continue rising into 2015.

The London Metal Exchange has recognized that the problems of warehouse queuing, delivery delay, premium fixing, and lack of transparency in aluminium pricing make the metal market susceptible to easy manipulation by a handful of large producers of the metal and traders. A month ago, on October 8, the UK Court of Appeal acknowledged that Rusal was engaged in a form of price rigging with an “unreal complaint” against new LME rules aimed at reducing warehouse delay and the profitability of metal premiums. Rusal, according to the court, was prejudicing “the integrity of the market by an unsustainable legal challenge.” Rusal was also accused by the court of stalling the court proceedings to prolong the period in which it could exploit the premium before new LME warehousing regulation might take effect. Rusal says it is applying to the Supreme Court for a review of the case.

Meanwhile, the premium has been rising while LME stock levels have been dropping; they are now down 17% since April:

Source: http://www.kitcometals.com

Does this mean that nothing the LME has done to date, including its London court win, and nothing it proposes or plans to do to curb the premiums by regulating the flow of metal in and out of its warehouses, will make any difference at all to the premium’s upward trajectory?

Geoff Sambrook, (right) a London metal trader, says: “the real price [of aluminium] is not LME plus premium. The LME price is at a discount to reality. In other words, the LME is not currently fulfilling its role as the market of last resort. The ‘real’ price of any commodity is the one at which that physical commodity changes hands. So in aluminium at the moment, the true price is (give or take) $2,400. That’s what consumers pay to producers, and whatever may be shouted by some, the producers are able and willing to fulfil consumer needs at that price. So, the LME price is lower. It’s lower, because if you buy LME, you can’t have it for a year or so, so clearly it is a less valuable item.

Geoff Sambrook, (right) a London metal trader, says: “the real price [of aluminium] is not LME plus premium. The LME price is at a discount to reality. In other words, the LME is not currently fulfilling its role as the market of last resort. The ‘real’ price of any commodity is the one at which that physical commodity changes hands. So in aluminium at the moment, the true price is (give or take) $2,400. That’s what consumers pay to producers, and whatever may be shouted by some, the producers are able and willing to fulfil consumer needs at that price. So, the LME price is lower. It’s lower, because if you buy LME, you can’t have it for a year or so, so clearly it is a less valuable item.

“Playing with load-in/out rates, and creating layers of complexity with premium contracts, is, in my view, unlikely to work. You probably could say Rusal is making a monkey out of them, but then the economic circumstances are on Rusal’s side. If we didn’t have interest rates where they are, Rusal would have had to shutter more production and would be stressed.

“It’s all about money, obviously. So long as the price Rusal (and others) can realise by selling metal into warehouse is more attractive than reducing production and letting the excess global stock be absorbed, they will continue to take the former course. And while the interest rate and forward price make a sufficient and risk-free return for the financiers — that’s traders, banks, investment funds — they will also continue to play the game.

“So Deripaska is right when he says the situation will continue into next year. LME stocks are declining, but it is my firm belief that the largest part of what is leaving LME is simply heading for private storage. So the overall total in warehouse is probably not changing significantly, it’s just less visible. And any LME rule changes can only apply to LME warehouses. So, for as long as storage remains the most profitable destination for metal, the game will continue. I guess you could describe that as a situation where Rusal, Glencore et al. are able to control the flows of metal.”

According to Andrew Home , an aluminium specialist and senior metals columnist for Reuters, “the core trade when it comes to aluminium is the stocks financing trade (aka the cash-and-carry trade). With LME aluminium in contango – that’s when the forward prices are higher than spot prices – the trade makes money by buying spot and selling forward. The costs are storing the metal, insuring the metal and borrowing the money to buy the metal. For a major bank the cost of the latter is a big zero. Insurance is fixed and relatively marginal. The profit of the whole thing, therefore, depends on how much storage costs. LME storage is exponentially higher than non-LME storage, which is why everyone is queueing to get their metal out of the LME system.

According to Andrew Home , an aluminium specialist and senior metals columnist for Reuters, “the core trade when it comes to aluminium is the stocks financing trade (aka the cash-and-carry trade). With LME aluminium in contango – that’s when the forward prices are higher than spot prices – the trade makes money by buying spot and selling forward. The costs are storing the metal, insuring the metal and borrowing the money to buy the metal. For a major bank the cost of the latter is a big zero. Insurance is fixed and relatively marginal. The profit of the whole thing, therefore, depends on how much storage costs. LME storage is exponentially higher than non-LME storage, which is why everyone is queueing to get their metal out of the LME system.

“Right now the profits from the stocks finance trade are pretty slim, even if you are storing the stuff in cheaper non-LME sheds. But then, if you’re earning, say 2% to 3% per annum equivalent from the trade, it’s still a lot better than just about anything else in the fixed income sector. And there’ s very little risk. You know exactly in advance your costs and your profits. There are a lot of banks doing this, and, I suspect, there are a lot of their customers doing it as well.”

Home notes the aluminium trade has made bad miscalculations. “One of the reasons premiums shot up at the start of this year was because investment banks had taken short positions in the market on the assumption that premiums would fall. When they moved sharply higher in the last week of December 2013, those banks had to scramble to buy physical metal to back off their paper positions. That shows you how even the ‘illuminati’ have been caught off-guard in this market.”

There is no consensus among aluminium traders over how large the volume is of metal in stock at non-LME warehouses. Ed Meir, (right) a New York trader, estimates there are “3 to 4 million tonnes off exchange, 4.5 million on exchange. I don’t know what is held as working producer stocks or in the Chinese Government’s stockpile.” According to Meir, the trend for all stocks “is decreasing. The overall balance of supply and demand seems to be a deficit.”

There is no consensus among aluminium traders over how large the volume is of metal in stock at non-LME warehouses. Ed Meir, (right) a New York trader, estimates there are “3 to 4 million tonnes off exchange, 4.5 million on exchange. I don’t know what is held as working producer stocks or in the Chinese Government’s stockpile.” According to Meir, the trend for all stocks “is decreasing. The overall balance of supply and demand seems to be a deficit.”

Home thinks differently. “High physical premiums tell us that metal is not readily accessible and that if you need some, you will have to pay richly for it. Rewind a year or so, and everyone would have linked that lack of availability to the amount of metal waiting load-out in LME queues. But with around 7,000 to 9,000 tonnes leaving the LME system every day (under new accelerated load-out rates), that’s not a good enough explanation. So, the inference is that metal is moving off the LME to a non-LME shed (much cheaper) to generate a better return for stocks financiers. It is no more available to a physical market buyer than it was sitting in an LME load-out queue. The only thing that has changed is that we have lost statistical visibility on that metal.”

“I would say that until a year or so ago, there were around 5 million tonnes in LME storage and most people assumed there were about the same in off-market storage. China doesn’t count, because no-one has any idea whatsoever of stock levels in that country. All other things being equal, which they never are, off-storage stocks should be rising as LME stocks fall.”

Pani Klikis, a London aluminium trader for Minimet, Mitsui, Trafigura and now LN Metals, estimates the off-LME warehouse stocks may be as much as double the LME volume. “My estimate [of the non-LME stock volume] is anywhere between 5-10 million. Both LME warrant and Western physical off warrant stocks are decreasing, and will continue to do so. The metal holders’ objective is to put money in the bank and one can only achieve that by selling.”

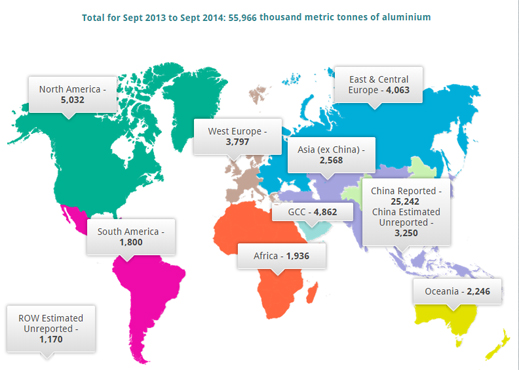

The World Aluminium Organization estimates that in the year to the end of September 2014, China produced 25.2 million tonnes, dwarfing the rest of the world, including Rusal. But another 3.3 million tonnes (12%) is estimated to have been produced in China, unreported. How much of the combined total has been sold, how much stockpiled isn’t known outside China. Rusal’s annual production was 3.9 million tonnes in 2013; it is likely to be 3.6 million tonnes this year.

WORLD PRODUCTION OF ALUMINIUM, SEPT 2013 TO SEPT 2014 — TOTAL 56 MILLION TONNES

Source: http://www.world-aluminium.org

Consultants to the Chinese mining industry, who ask for anonymity, say they won’t hazard a guess about the Chinese stock level. But they believe the trend is for that volume to be decreasing.

“China is a mystery,”Klikis says. “they must have stock but I have no idea how big it is. China has started to split in two with additional capacity in the northwest, and reduced capacity in the northeast and southeast of the country. An imbalance has been created whereby China is long and the rest of the world is short.” Klikis acknowledges that the western aluminium trade has little idea of Chinese intentions. “LME stocks will continue to decrease and in the face of continuing reduction in stocks, the premiums will continue to rise. Unless Western producers will start up capacities. Or China start leaking metal.”

Home of Reuters also warns: “the main threat to this new market optimism comes from China. Production there is still rising. More disconcertingly, so too is the stream of semi-manufactured products leaving the country…. The danger, of course, is that Chinese surplus metal moves in sufficient quantity to fill any evolving Western deficit… the tensions between Chinese surplus and Western deficit are only likely to become more acute, as long as the underlying respective trends of rising and falling production continue.”

Leave a Reply