By John Helmer in Moscow

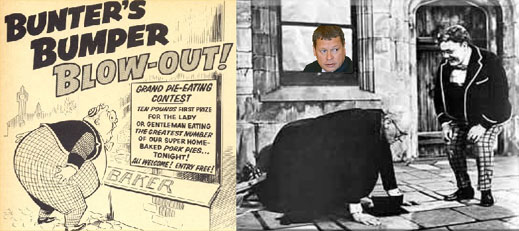

Billy Bunter was a fictional schoolboy character well-known to British and colonial schoolboys of my generation. Like most of us, his eyes were bigger than his stomach. Unlike many, by the age of ten Bunter had grasped the concept of leverage — to feed himself he was always borrowing against the legendary postal order that was in the mail from his Pater. To assist in his cons, Billy was also a gifted ventriloquist, making voices appear to come from everywhere but himself. This was always amusing even though — maybe especially because — Bunter was usually caught out, and either caned by his school masters, or kicked by his classmates. (You can have a Russian empire if naughty boys get away with their japes, but not a British one.)

Igor Zyuzin is an equally talented ventriloquist, when it comes to promoting the market prospects and share price of the Mechel steel and mining group, which he owns and also runs. He also has a famously large appetite; extreme leverage at the moment; and a soreness on the backside, where Prime Minister Vladimir Putin gave him a dozen of the best in front of the nation, fifteen months ago. Unlike Bunter, Zyuzin has no sense of humour, not in public at any rate. He even denies the most obvious of his strategems.

Still, with the rise in the global price of his principal moneymaker, coking coal, and the promise of a very large postal order from China in the mail, Zyuzin is feeling confident that soon he will be able to revive his plan to spin off the group’s coalmining assets into a separately listed company, and sell the shares to someone else. At least, this is what Zyuzin’s ventriloquism appeared to be saying last Friday.

According to Zyuzin’s deputy, Mechel senior vice president Vladimir Polin, “we plan to sell shares of Mechel Mining as soon as financial markets recover.” The earliest that could be would be next year, Polin added in an interview with Moscow reporter for Bloomberg, Ilya Khrennikov. Polin also said that Mechel is looking at stock exchanges like Hong Kong, and its choice will depend on investors’ preferences. Hong Kong is being considered, according to Polin, because of the increasing dependence of Mechel’s exports on the China market. More than 30% of the group’s exports — mostly of coking coal — will go to China this year, up from about 5% in 2008, Polin said.

Mechel spokesman Ilya Zhitomirsky responded by telling CRU Steel News: “It is wrong, Bloomberg was mistaken”. Khrennikov told CRU Steel News that Polin had been quoted accurately.

Polin’s remark was followed by a brief rally in Mechel’s Moscow and New York listed share price on Friday. By the end of trading, however, the share had fallen almost 3% to $20.50, with a current market capitalization of $8.5 billion.

The embarrassment apparently caused to Zyuzin by the premature announcement stems from the reaction of the Russian government when he first proposed the spinoff last year. Mechel sources initially told CRU Steel News in February of 2008 that they were considering a listing of the coal-mining division on the Frankfurt stock exchange, with the sale of a 15% to 20% shareholding. Three groups of coalmining assets were reportedly to be included in the spinoff company and separate listing — Yuzhkuzbass, Yakutugol, and Elgaugol. Excluded was Mechel’s nickel mining operation, which supplies nickel for the company’s stainless steel division. It was also unclear whether Mechel’s iron-ore mine, Korshunovsky, would be included in the spinoff, or retained in the steelmaking group. Three months later, in May of 2008, Mechel announced that its mining division would include the iron-ore unit, along with the coal mines, and it began to buy out minority shareholders in the assets. The company allowed speculation that it would go to London for the IPO.

Then in July, Putin launched a stinging attack on Zyuzin, and followed with a government investigation of coal price rigging and restrictive supply tactics. The change in public sentiment caused a sharp decline in Mechel’s share price, even before the global crash of steel and coal demand and trade began in September. Putin’s caning took about $13 billion off Mechel’s market capitalization.

Since then Zyuzin has sought to repair his relationship with the government, and secure the company’s indebtedness and forward investment commitments by a combination of state bank loans and state financing guarantees. As part of the quid pro quo for state support, Zyuzin has also agreed to Mechel’s steel division taking over operational and financial management of four bankrupt steelmills formerly owned by Vadim Varshavsky’s Estar group. As potential liabilities on the balance-sheet, Zyuzin isn’t comfortable with the Estar assets, but he hasn’t been given any choice in the matter. That’s the principal reason he and the Mechel spokesman will not agree to talk about the terms of the takeovers and the financial exposure to Mechel’s profit line.

A morning report from Unicredit Equities in Moscow believes the IPO for the coalmining division is also being backed by Mechel’s banks as a way to reduce the group’s heavy indebtedness. The report by metals analyst George Buzhenitsa estimates that in the present coal market, the coal company spinoff could reach a market valuation of from $8 billion to $10 billion. The sale of a 20% stake would thus generate up to $2 billion in cash to set off against the aggregate debt at present of $5.5 billion. According to Buzhenitsa, ” we note, however, that the IPO process may be complicated by pledge agreements with the company’s lenders (35% of the shares in Yakutugol and Southern Kuzbass Coal Company are used as security for a USD 1bn loan with Gazprombank).”

The Billy Bunter way of looking at the problem isn’t so cautious. Because Zyuzin is believed to have pledged much of his 70% stake in the group to secure his foreign bank lenders — ABN AMRO, BNP Paribas, Calyon, Natixis, Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation Europe Limited, Société Générale Corporate & Investment Banking, and Commerzbank Aktiengesellschaft — he must generate some quick cash to clear their debt, and release his own shares. But he can’t get away with that, unless the Russian government orders the state banks (including Gazprombank) to agree. And that hasn’t happened yet. So Zyuzin threw one voice to announce what he’d like to do, in the expectation of raising appetite for his coalmining shares. Then he threw a second voice to deny anything like that had ever been said.

Leave a Reply