By John Helmer, Moscow

![]() @bears_with

@bears_with

If Russian money talks, there can be no doubt it is telling President Vladimir Putin to give Russia’s relationship with Turkey a priority comparable, almost, with China and India. The message eliminates Greece from the Kremlin’s consideration; it also diminishes Cyprus.

But does this mean there is a powerful Turkish lobby working inside the Kremlin? Does it mean that Russia’s shift on the economic front towards Turkey is causing a strategic switch, reversing the three-hundred year history of tsarist, imperial and Soviet military and security strategy? Can the Turkish Air Force ambush of a Russian Su-24 fighter and murder of one of its pilots in November 2015; the assassination by a Turkish policeman of Ambassador Andrei Karlov in December 2016; eighteen months of embargo on Turkish imports to Russia, December 2015 to June 2017; and the failure of the Idlib pact of September 2018 have all been erased from Russian memory, to be replaced by the trust Russian officials now insist they have towards their Turkish counterparts?

As the Turkish military begin deploying their newly delivered Russian S-400 missile batteries, first around the capital Ankara, and then in southwestern Turkey covering the airspace and territorial waters of Cyprus and Greece, Greek sources believe Russian strategy has broken with Russian memory, and will now side with Turkey in the expansion of its claims to the seabed oil and gas of Cyprus and around the Greek islands of the Aegean.

Eight Russian experts on Turkey, the eastern Mediterranean and the Balkans, employed by Moscow think-tanks, government consultancies, and the press were asked to assess this view, and also to say if they believe there is a Turkish lobby influencing Putin and the Security Council. The questions are so sensitive, however, not one agreed to respond either on or off the record.

“I find it hard to believe that the Russian ‘deep state’ relies on Turkey as a long-term ally”, a retired Russian official and veteran of many years of policymaking with Greece, Turkey and other Black Sea states, says. “Historical memory is also there — we have many reminders.”

The Russian source adds that the Greek prime ministers have only themselves to blame for Russia’s re-calculation. “In the case of [former prime minister Alexis] Tsipras, it was easy — he was a fake, and many people suspected that from the outset. So why should Russia have tried to strike a deal with a fake that would yield nothing. With or without Russian interaction with Turkey, Tsipras would have acted in exactly same way on practically all issues: Russian-Turkish relations were just his excuse. Nea Demokratia and the families in the Greek hereditary political establishment, such as Karamanlis or Mitsotakis, might be slightly more reliable partners than the Syriza clowns.”

“I think that Greeks are making a mistake. Early or later, Turks will come for their throat – for example, to reclaim the islands adjacent to Turkey, paying no mind to the American bases in Souda, Larissa, etc., because they know that the Americans will not intervene militarily, just as they didn’t in the past. It is just a matter of time. A country like Turkey can afford waiting a century or two. The Albanian expansion which the Americans endorse and EU stupidly disregards will improve Turkey’s strategic standing in the Balkans.”

At a press conference in Ankara last August, Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov spoke the term “strategic partnership” with Turkey to describe “the choice of our countries in foreign affairs.”

Left to right: Sergei Lavrov speaks during a press conference with Turkish Foreign Minister, Mevlut Cavusoglu, in Ankara on August 14, 2018. Source: http://www.mid.ru

Putin has not used the term “strategic partnership”. He has described the work of a bilateral “Joint Strategic Planning Group” between the Russian and Turkish Defence Ministries; he has also described “the progressive development of Russian-Turkish partner relations that have confidently reached a strategic level in certain areas.” By that last phrase, Putin has meant energy projects.

Presidents Putin and Erdogan seated on Ottoman thrones in Istanbul on November 19, 2018, following a ceremony marking the completion of the Turk Stream gas pipeline’s offshore section. Source: http://en.kremlin.ru/

Last November, at the completion of the offshore gas pipeline section of Turk Stream, Putin said “I am confident that Turk Stream, just like our other joint strategic project, Turkey’s first Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant, will become an outstanding symbol of the progressive development of the Russian-Turkish diverse partnership and a pledge of friendship between our nations.” He added: “I would like to say that the trade turnover [target] Mr President [Recep Tayyip Erdogan] has just mentioned, $100 billion, will be actually Russia’s bilateral trade with China this year. But then, why should Russia’s trade with Turkey be smaller? I have no doubt that we can and will attain the same target in our relations with Turkey.”

A few days ago, on June 28, Putin told Erdogan at their meeting in Osaka, Japan: “We both know that either side has a significant investment volume of $10 billion each”. At this level, Turkey is now the fourth largest destination for Russian foreign investment. But since Cyprus, British Virgin Islands, Switzerland and the US are all havens for Russian flight capital, Turkey represents one of the largest sites for real Russian investment.

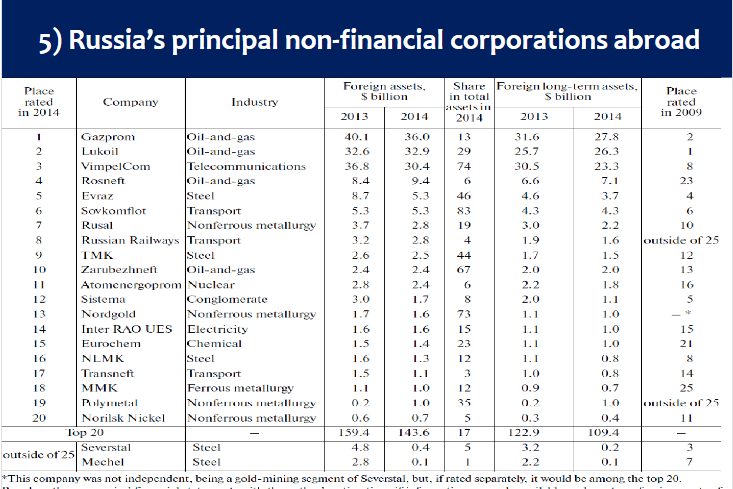

CLICK TO ENLARGE

Source: https://www.researchgate.net/

Just how real is indicated by the evidence that it is Russian state companies which are the sources, not the private sector oligarchs.

Source: https://www.researchgate.net/

Gazprom’s Turk Stream investment is currently estimated at €11.5 billion for a combination of domestic gas deliveries and gas for export. Gazprom is sanctioned by the US.

Rosatom, the state nuclear conglomerate, is investing even more in the Akkuyu project. Intended to supply about 10% of Turkey’s electricity needs, the total cost is about $20 billion. Of that Rosatom has proposed to take a 51% investment stake, and possibly to pay all construction and installation costs up front. However, to date there is reluctance of Turkish investors to participate. For the time being the bill is being paid by the Russian side. Rosatom is not on the current US sanctions list.

The sale of the S-400 by the Russian Technologies (Rostek, Rostec) arms export division is estimated to be costing the Turks $2.5 billion, although the terms, including Rostek’s “investment” in long-term credit and offset arrangements, have not been officially disclosed. Rostek and its chief executive Sergei Chemezov are sanctioned by the US.

Vagit Alekperov’s LUKoil – now under US sanctions — operates more than six hundred petrol stations in Turkey, supplying them with LUKoil’s refined products. They represent a 5% share of the motor fuel market in the country; LUKoil doesn’t report their revenues or earnings. Investment in Turkey is said by the company to be worth about $1.5 billion at present and may grow.

“We greatly appreciate our partner’s’ refusal to join the anti-Russian sanctions,” Lavrov said at his press conference in Ankara last August. This, not memory loss, is the touchstone of current Russian policy, Moscow sources believe. As stones go, it’s not a small one. The readiness of Greece and Cyprus to go along with US sanctions – and recently to expand on them – has been reported here.

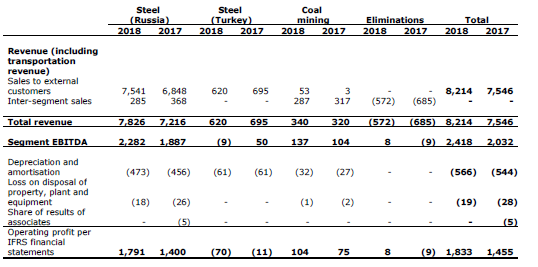

The private oligarchs haven’t been keen on Turkey. Mikhail Fridman has abandoned his Vimpelcom investment in the Turkish mobile telephone market. Victor Rashnikov’s Magnitogorsk (MMK) steel group has invested in two steelmills in Iskenderun and Istanbul since 2007, primarily to assure the volume of imports of MMK’s crude steel; commercially the Turkish business has been lossmaking since 2017. As the Turkish currency has collapsed and steel sale revenues have dwindled, Rashnikov’s investment had a book value at December 2018 of $476 million; that was roughly half of what had been reported in 2016. But in the financial report for last year, issued this past February, MMK’s accountants required a writedown of $258 million.

MAGNITOGORSK METALLURGICAL COMBINE’S (MMK) MILLS IN TURKEY

Source: http://eng.mmk.ru/upload/iblock/5a6/MMK_IFRS_2018.pdf – page 33.

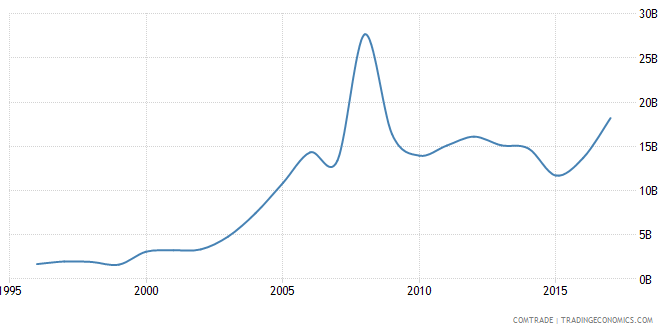

Except for tourism, trade between Turkey and Russia has had its ups and downs for years; it was far from stable even before the shoot-down of the Su-24 in November 2015 triggered a Russian trade embargo; for details of Turkish collaboration with the US military in that episode, read this. In combined turnover, the trade has struggled to sustain the $25 billion level.

RUSSIAN EXPORTS TO TURKEY, 1995-2017

In billion USD

Source: https://tradingeconomics.com/

TURKISH EXPORTS TO RUSSIA, 2008-2017

In million USD

Source: https://tradingeconomics.com/ Russian tourism to Turkey, now at a record level, comprises about one-quarter of the export revenues.

Last year the trade turnover rose 15% to the $25 billion mark it had reached before the global trade downturn of 2008. But for Turkish food exports to Russia to improve on this requires overcoming the Russian farm lobby, which gained significantly from the ban on Turkish tomatoes and other fruit and vegetables in 2016-2017, as well as from the countersanctions on EU food imports introduced in August 2014.

Left, Dmitry Patrushev, Russia’s Agriculture Minister, meeting his Turkish counterpart, Bekir Pakdemirli (right) in Ankara in May. Patrushev, the son of Security Council Secretary Nikolai Patrushev, cannot risk being seen to lobby his father for Turkish exporters over domestic producers. The quadruple target for trade to $100 billion, announced by the presidents, cannot be achieved by Kremlin disregard of Russian farm and agro-industry interests.

Turkish money also talks through investment in Russia. The aggregate is currently running at about $10 billion; one-quarter of this is concentrated in the predominantly Muslim republic of Tatarstan. A Kremlin-sponsored effort to add another €900 million in state-secured support for Turkish investment in Russia has been announced recently by the Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF).

Still, the money is paltry and unpersuasive compared to the historical precedents. The Russian military and intelligence services are well aware of Turkish unreliability, duplicity in fact, before and after Putin and Erdogan concluded their agreement on security arrangements around Idlib in Syria last September; for more, read this. According to one source, “Turkish promises are like Turkish delight. They stick in the mouth.”

Russian strategists won’t say so publicly in the present situation of US and EU war against Russia. However, they aren’t blind to serious conflicts of interest with the Turks in northern Syria; in their gasfield ambitions in the eastern Mediterranean; in Iraqi Kurdistan; and in their old Ottoman ambition to recover sway over the Balkans through Kosovo, Albania and northern Macedonia. They don’t differ from the Israeli ambassador to Turkey who wrote in 1953: “good relations [with Turkey] could deteriorate ovemight, and we should learn from the bitter experience of others. The Turks have yet to achieve a standard by which, in the event of disagreement with another state, they can weigh up the positions of both sides. For them, there exists one sole principle: in any conflict with a foreigner, whether a private individual, a company or a state, the Turk is always right.”

Foreign Minister Cavusoglu was following this script to the letter when last week he warned Russia not to support Syrian Army operations covered by the Idlib pact of last September. “Trust between Turkey and Russia is discussed between the presidents of both countries. Idlib is an important topic from a political and humanitarian point of view. The attacks on Idlib must be stopped. Russia needs to keep under control the forces of the [Syrian] regime.”

Radio silence was also broken last Friday by the Moscow daily publication Vzglyad with a series of warnings of the deployment plans for the S-400 “to help Turkey to produce gas in the Mediterranean Sea.”

Semyon Baghdasarov, director of the Moscow Centre for the Study of the Middle East and Central Asia, was quoted as warning that “Turkey is concentrating its Navy forces in the region to protect drilling rigs, which, of course, is dangerous. Strictly speaking, these are the territorial waters of Cyprus. This water area is located far even from Northern Cyprus, which was occupied by the Turks. Can Erdogan go further in this adventure? This cannot be excluded, given the character of this man. But then that’s a war with the EU.”

For the first report of the strategic implications of Turkish deployment of the S-400 in western Turkey, read this.

This Turkish map under-estimates the 600-km range of the S-400 if deployed on Turkey’s southwest coast, near Izmir.

The Russian Foreign Ministry started to withdraw from its unqualified support for Cyprus in June, when Ambassador Stanislav Osadchiy proposed fence-straddling between the sides. “The increase of tension is not a solution,” he told a Cypriot newspaper. “This is why we believe that each side must avoid such steps that aggravate the situation in the Mediterranean.”

On July 8, the Foreign Ministry in Moscow issued more of the same, carefully avoiding criticism of the Turks. “In connection with incoming reports on the visit of yet another Turkish ship to conduct geological prospecting in the exclusive economic zone of Cyprus, we are watching with concern the developments in this area. We believe that any violation of Cyprus’s sovereignty can only hinder conditions for a durable, viable and fair resolution of the Cyprus issue. We urge all countries to refrain from steps leading to the buildup of a crisis potential in the Eastern Mediterranean, to display restraint and political wisdom, and to strive to resolve any dispute through dialogue and respect for each other’s interests.”

In last week’s Vzglyad, Konstantin Sivkov is cited as a warning that the Turkish S-400 is “a serious argument in [Turkey’s] insistence on continuing research in the territorial waters of Cyprus.” Sivkov is First Vice-President of the Academy of Geopolitical Problems in Moscow. Once the S-400 is deployed, he said this “will exclude any possibility of using Western aviation against Turkey.”

This fresh deterrent to NATO and US operations from Italy, Greece, and the British bases in Cyprus, isn’t unwelcome to the Russian General Staff, especially as the US has been increasing the range and intensity of its attack capabilities, including missiles and drones, from Crete and mainland Greek bases. Russian S-400s are already in operation at the Syrian base of Hmeimim. But the range of the S-400s may be extended westward by up to a thousand kilometres, depending on where the Turks decide to deploy their batteries and how often to move them. For example, from the Turkish airbase at Gaziemir, near Izmir, southwest to the US air and naval base at Souda, Crete, is a radar surveillance and missile attack range of just 400 kilometres. Other deployment locations reported in the Turkish press between Antalya and Adana are between 600 and 1,000 kms from Crete, but much closer to Cyprus.

The General Staff, Defence Ministry and GRU are the most skeptical of Russia’s strategic decision-makers towards the new trust in Turkey publicly espoused by President Putin. The Kremlin spokesman, Dmitry Peskov, a fluent Turkish speaker whose family has been on Turkish payrolls, is the most positive; for the Peskov story, read this.

Erdogan may consider Peskov his Kremlin asset, but his high opinion of the spokesman isn’t shared by uniformed and civilian Russian decision-makers.

Since George (junior) Papandreou a decade ago, and more recently Alexis Tsipras have discredited Greek policy with their less than secret US ties, there has been no countervailing Greek lobby in Moscow. “Unfulfilled promises, corruption scandals and the Macedonian issue – these are the three main reasons for the defeat of… Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras in the elections,” Vzglyad reported one Moscow academic as commenting. “The defeat of the party of Alexis Tsipras is natural.” He added that no serious worsening of Russian relations with Greece can be expected now because “they are already at a very low level, because of the scandal that broke out last year, which ended with the mutual expulsion of diplomats. The scandal has since managed to be hushed up a little, but the hopes which were laid on Russian-Greek relations a few years ago have clearly not been justified.”

There was a brief flurry of optimism when Kyriacos Mitsotakis visited Moscow in February of this year, still in parliamentary opposition at the time. The only Russian investment in Greece Mitsotakis was able to mention was the €20 million acquisition of dairy producer Dodoni by Wimm Bill Dann in 2012.

Left, New Democracy head Kyriacos Mitsotakis; right, Speaker of the State Duma Vyacheslav Voloshin, February 28, 2019. Russian expert and press commentary on Tsipras’s election defeat by Mitsotakis on July 7 has unanimously regarded it as good riddance. Among the first acts of the new Mitsotakis foreign ministry announced last week, there is the recognition of the US-backed rebel Juan Guaido as president of Venezuela.

Eight Moscow experts in military and security strategy were asked to identify who they believe to be the most pro-Turkish figures influential in Kremlin policymaking, and whether they regard the S-400 sale as a sign of a strategic shift in Russian-Turkish relations. Each agreed to consider the questions if re-sent by email. Not one was willing to answer, on or off the record.

“There’s no need for a Turkish lobby to produce the Kremlin’s current line towards Erdogan,” a source requesting anonymity comments. “It’s the natural consequence of the war the US and the EU are fighting against Russia. Since Greece’s alignment with Washington is obvious, its influence in Moscow is zero. Cyprus under [President] Anastasiades has long been heading that way. If Greeks want to blame us, that’s putting the cart before the horse. The Trojan horse, in this instance.”

“There’s also no reason for the Russian military or the strategic analysts to broadcast their skepticism towards the stability of Turkish policy. That goes without saying.”

Leave a Reply