By John Helmer, Moscow

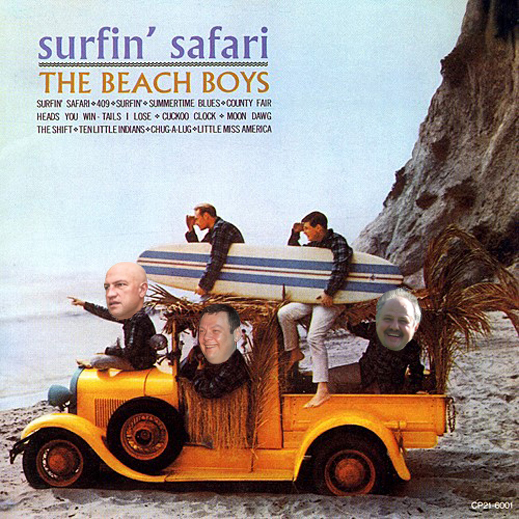

Mikhail Fridman (lead image, centre) and Alexei Reznikovich (left) have a telephone problem, and it’s got a name, Gregory Shenkman (right).

It’s not that Vimpelcom, the global mobile telephone company they control through LetterOne (L1), Fridman’s offshore holding, isn’t a lucrative business. In market capitalization Vimpelcom is currently worth $8.7 billion; it dropped from $18 billion in 2010 to $3 billion at the start of this year, and is now up almost threefold. Volatility like this indicates the market sentiment that conventional telephone companies have hit the limit of their value. To grow richer, the telephone companies must do new things. And for the technology to do that, Fridman and Reznikovich admit they must find assets which Russia isn’t producing at present.

For Russian nationals, that’s easier said than done right now. For Vimpelcom to grow, LetterOne is thinking of buying the wherewithal in Silicon Valley, California. That may be the heartland of the technology Fridman and Reznikovich want. It’s also the belly of the beast, so far as the Kremlin and Russian security forces believe, because of the Ukraine sanctions campaign; NATO’s military reinforcements along Russia’s frontiers, and the US Government’s effort to force regime change in Moscow. Trading with the American enemy is an increasing concern at Vimpelcom, because the Kremlin insists; and because the US Government is preparing to strike at Vimpelcom for alleged bribery in pursuit of its international business. So what have Fridman and Reznikovich engaged Shenkman for?

Shenkman, 54, is a Russian-speaking American from San Francisco, whose family came from Kiev to the US during the Soviet Jewish emigration of the 1970s. Speaking from California last week, he doesn’t want to reveal what he is now doing with Fridman and Reznikovich. The Shenkman file is a secret they are trying to keep, too.

Shenkman is reputed to have been the entrepreneur behind Genesys and Exigen, two high-technology start-ups in California, which have provided conventional telephone networks and the businesses using them with applications, and programming technology, to add value to the business of communicating. Genesys was started with a few hundred thousand dollars and then sold for $1.5 billion, making Shenkman a fortune, but only after he was ousted as chief executive and lost his board seat.

Exigen was his sequel. But Russian investors have discovered that it is an insolvent shell, and Shenkman’s money has gone. According to one of the investors, “the idea was to quickly repeat the success of the Genesys IPO, then exit through another selloff. But the timing was wrong, and the business model flawed. Shenkman was investing against the market. He fell out with his partners.” Shenkman’s debts now threaten him with litigation in San Francisco, Moscow, and because LetterOne is headquartered in London, in the UK courts too.

California court papers and commercial records show that Shenkman’s Exigen companies are broke. Since 2012 he and they have been targeted for liens to cover debt claims from federal and state tax authorities, from law firms and other suppliers. Shenkman himself is facing the courts for sexual offences, court papers call his companies “a breeding ground for sexual harassment.”

In October 2013 Exigen USA Inc. filed for Chapter 11 voluntary bankruptcy. More than 40 creditors were identified, including the tax authorities, lawyers, and other companies in Shenkman’s group. Just how indigent Exigen is can be read in this court filing. Shenkman himself, citing a home address in Tiburon, California, puts himself down as a creditor. Offshore entities in Bermuda, Germany and The Netherlands hint at where Exigen money may have gone, then moved on, leaving debts behind.

In August 2014, Universal Music Investments, an affiliate of the Warner Music Group, won a judgement in a Delaware state court against another of Shenkman’s Exigen companies, claiming the bankruptcy of Exigen USA didn’t shield Exigen Ltd. from having to pay the original judgement; this appears to have been for about $360,000. In that case, which commenced in 2010, Universal Music charged Exigen with breaking its contract and failing to develop the software promised for tracking royalty payments owed to Universal Music.

When Shenkman did his initial deal, Universal Music announced its joint venture company with Exigen, called Royalty Services LP, “will build and operate systems to process royalties for the millions of transactions currently handled by the information technology departments of Universal and WMG… Royalty Services LP also plans to offer its royalty transaction processing capabilities to other organizations in the media industry…to lower their processing costs… Exigen, the business process software and services company, was selected by Universal and WMG to provide the software and ongoing operational services for the joint venture because of its track record in delivering measurable financial value through process innovation.” The revenue value for this computerized accounting platform for royalties owed to pop music performers, songwriters, record companies and managers was more than a billion dollars in 2008, and has since multiplied substantially. At contract signing, the deal was worth $70 million to Exigen.

In 2009, according to the New York Times, Exigen had “$600 million in growth equity”. Today, according to California sources, Shenkman’s remaining operations are worth a small fraction. The Exigen Services website no longer works. The company telephone at its business address, 345 California Street, San Francisco , rings without answer. An eviction notice has been issued for the premises.

Moscow sources report that Shenkman’s Exigen group has received about $30 million from several Russian investors; they believe he is indebted to them. One accuses him of operating “an Enron-type scheme — he creates the asset as a concept; markets the idea; draws in investor funds; and then loses the money.” A Silicon Valley source estimates that between Shenkman’s sale of Genesys in 1999 and now, Shenkman “has burned through $300 million.”

Shenkman’s white knight and his largest investor has been Ukrainian oligarch Victor Pinchuk, through his London-based EastOne holding (right). Gennady Gazin, chief executive of EastOne in 2008, told the media “we have helped set up a mid-sized US-based private equity fund, Exigen Capital.” Sources in London claim that between 2006 and 2009 more than $260 million was invested in Exigen by Pinchuk. His associates do not respond to questions about what they are owed by Shenkman. EastOne continues to report its position in Exigen spinoffs, such as EIS Group, which appear no longer to be connected to Shenkman.

Shenkman’s white knight and his largest investor has been Ukrainian oligarch Victor Pinchuk, through his London-based EastOne holding (right). Gennady Gazin, chief executive of EastOne in 2008, told the media “we have helped set up a mid-sized US-based private equity fund, Exigen Capital.” Sources in London claim that between 2006 and 2009 more than $260 million was invested in Exigen by Pinchuk. His associates do not respond to questions about what they are owed by Shenkman. EastOne continues to report its position in Exigen spinoffs, such as EIS Group, which appear no longer to be connected to Shenkman.

Moscow sources say they understand why Vimpelcom and LetterOne want to build on their telecommunications networks the type of applications which attracted Universal Music in the US. “At the get-go, Shenkman is a good salesman for asset acquisition,” one of the sources says. “But can Fridman and Reznikovich not know Shenkman’s recent record?”

Last week it was confirmed that LetterOne and Shenkman are finalizing a business agreement with a San Francisco law firm, Fenwick and West. The attorney in charge is Michael Solomon. He describes himself on the firm’s website as a specialist in venture technology tax, along with “intercompany transfer pricing, foreign tax credits… tax-favorable foreign corporate structures and financing techniques, foreign acquisitions and restructurings, sourcing, intellectual property planning and tax accounting solutions arising out of the foreign operations of U.S. based multinationals.”

Solomon (right) was asked to clarify what relationship is in planning between LetterOne and Shenkman. He responded that “whatever information I might have I can’t disclose because of attorney-client privilege.” He declined to confirm whether LetterOne or Shenkman is his client.

Solomon (right) was asked to clarify what relationship is in planning between LetterOne and Shenkman. He responded that “whatever information I might have I can’t disclose because of attorney-client privilege.” He declined to confirm whether LetterOne or Shenkman is his client.

Reznikovich recently told the Financial Times “the old fashioned telecoms industry needed a root-and-branch overhaul to make money for investors… to acquire businesses in areas ranging from traditional telecoms groups that needed help or new capital, to internet companies such as those making apps and streaming services that could be used by its global mobile operations.”

Registered in Luxemburg and headquartered in London, LetterOne is to be the holding company for the 48% stake in Vimplecom held by Fridman and his Russian partners. The holding will also control their 13% shareholding in Turkcell, the Turkish telecommunications company, which is being contested with the Turkish government and Mehmet Emin Karamehmet. Altogether, these assets are estimated to be worth about $14 billion.

This month Reznikovich was asked if his asset targets are likely to be in the US and EU, and if so, how LetterOne intends to address the Russian government’s security concerns. He refuses to reply; he won’t say if Shenkman is a Russian security risk to the Americans, or an American security risk to the Russians.

In Moscow Fridman was asked the same questions. His spokesman at Alfa Group, Natalia Dymova, referred the questions to Alfa Bank headquarters, which said Fridman would answer through Vimpelcom. He hasn’t.

Scandinavian and Russian industry sources acknowledge there is now heightened concern about “Trojan horses” in the software systems operated by Russian telecommunications companies outside Russia, and NATO-controlled telecommunications companies connected to the Russian operators. At Vimpelcom, this is evident in the relationship with Telenor, the Norwegian state-controlled company which votes 43% of Vimpelcom’s shares. A Scandinavian expert acknowledges the relationship between Telenor and Vimpelcom, like that between TeliaSonera of Sweden and Alisher Usmanov’s Megafon, is increasingly under strain from the security services of Russia, Norway, and Sweden. “Before the Ukrainian conflict they were more concerned about corruption in their businesses in places like Uzbekistan. Now the problem is who is spying on whom – and how.” Click to open TeliaSonera’s story.

In federal New York court action launched on June 29, and then in a forfeiture ruling last Friday, July 10, the US Government attacked Vimpelcom with charges of bribery in Uzbekistan, but left TeliaSonera almost unscathed. For the new US court move, click to read. For the record of soft-pedaling in Sweden, read this.

Vimpelcom disclosed last month that it has been obliged to replace Mikhail Slobodin (below, left) , its head of Russian operations since 2013, with Alexander Krupnov (right) whose state security clearance is more secure. Krupnov moves up, Slobodin keeps his job, but moves down a notch, and is reportedly to be excluded from access to state secrets. The reason reported in Moscow is that Slobodin holds a residency visa in a foreign country. Vimpelcom won’t say where. Krupnov has served in the past as head of the state telecommunications agency. Kommersant reports he “will be responsible for customer service from the military and intelligence services.”

Russian media reports don’t reveal Shenkman’s current operations in Moscow and St. Petersburg. When internal corporate troubles pulled Shenkman and Exigen apart, Russian industry media omitted the details. Moscow analysts understand Fridman’s strategy, but not Shenkman’s role. According to Anna Milostnova of UFS, “the conventional communication services have increasingly exhausted their growth potential. In the new market, L1 can be called a technologies rookie.”

Last week in Moscow Vimpelcom told investors it is shifting its revenue focus from regular telephone tariffs to data bundles and apps. There was sceptical reaction, because the company says it is expecting sales growth this year of no more than 1% in rouble terms, while inflation in Russia is expected to reach 11%.

According to Raiffeisen telecommunications analyst, Sergei Libin, “LetterOne’s assets are at the intersection of telecomms and IT. As for the Kremlin’s position, it should be noted that, firstly, LetterOne is not under Russian jurisdiction, and secondly, many technology companies have users around the world and are not tied to a specific country. As an example of Russian investments in international assets there are DST Global’s Yuri Milner and Alisher Usmanov, who at different times has been a shareholder of such companies as Facebook, Zynga, Groupon.” About Shenkman’s role, he said he knows nothing.

Scandinavian sources aren’t familiar with Shenkman; they acknowledge the intensification of security concerns. According to a Stockholm source, “this trend started long before the Ukraine problems. The process will continue – it is an anomaly that Teliasonera and Telenor should have such strong positions in the Russian telecoms companies. This is bound to change.”

At present, the Swedish government holds 37.3% of TeliaSonera; the Finnish government, 7.8%. According to the Stockholm source, “at Megafon TeliaSonera has had very little insight into the day to day management of the company, and no access to the technology.”

A London source says: “With Fridman and Reznikovich Shenkman is trying to repeat the Genesys story. But what Fridman and Reznikovich think of the Exigen story and what business they plan to do with such American sources of technology is hard to say.” Reznikovich was asked to clarify LetterOne’s relationship with Shenkman. He won’t say.

In 2001, in a Russian media profile, Shenkman said “every business – in the field of hi-tech like any other – requires ideas. ..There are moments when, in addition to faith, you have nothing else: no guarantees, no money. Before us our business did not exist, we created a completely new business. We were doing a kind of new religion.”

Asked to say what he, Fridman and Reznikovich have agreed on, Shenkman said he will make no comments.

Leave a Reply