By John Helmer, Moscow

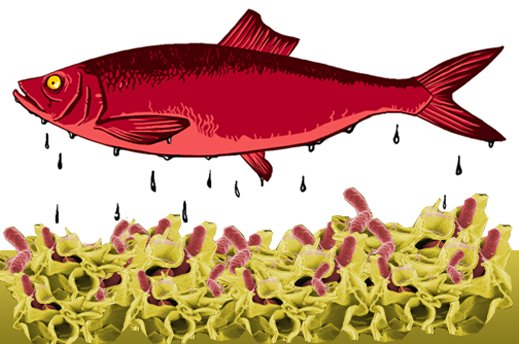

There is no family relationship between the fish and the bacteria; the latter are named after their discoverer, Daniel Elmer Salmon (1850-1914). But how much of a relationship there may be at the moment between salmonella in Norwegian salmon and Russian fish-eating security depends on another creature, the land-based red herring.

On the surface, according to Rosselkhoznadzor (RSKN), the federal service for veterinary and phytosanitary inspection, the half-billion dollar per year fish trade from Norway may be banned because of recent discoveries of salmonella and coliform infections in batches of imported salmon and other fish products. The threat was delivered in a letter, released on February 6, from RSKN to the Norwegian counterpart agency, referring to Russian laboratory evidence of the dangerous substances in the Norwegian imports.

Below the surface, fish industry experts in Moscow suspect that the threat, yet to be implemented, is a warning to the Norwegian coast guard to stop arrests of Russian fishing vessels in the Svalbard waters of the Barents and Greenland Sea. Mikhail Anshakov, head of the Consumer Rights Protection Society told Fairplay in Moscow: “Rosselkhoznadzor had better control the domestic manufacturers, as the salmonella problem in Russian production is very serious. I believe that there is something behind the move against Norwegian seafood other than consumer protection.”

The threat is very big business for Norway. Its fish exports to Russia last year reached €679 million, about 10% of Norway’s total seafood exports; Russia currently ranks as Norway’s largest client for fish, ahead of France. Salmon exports to Russia came to €401 million.

Sergei Gudkov, chief executive of the fishermen’s lobby, the Russian Fish Union, denies the import ban threat is retaliation for Norway’s arrests of Russan trawlers at sea. Last year, industry announcements reported more than a dozen arrests of Russian vessels at sea. Despite agreement between Oslo and Moscow on delimitation of their maritime borders, Russia is not recognizing Norway’s exclusive fishing zone around Svalbard and Spitzbergen, where the vessel incidents have taken place. Gudkov told Fairplay: “It would be naïve to say that a state body like RSKN can’t be used as a political instrument, but this is definitely not the case with the Norwegian fish imports. RSKN’s mission is to monitor foods for possible threats, and they seem to have spotted one.” Asked if the Fish Union has statistics on the incidence of salmonella in the domestic catch, he said no.

Officials at RSKN were asked for statistics on the incidence of salmonella in domestic fish products. So far, there has been no response.

On Monday, the Fish Union issued a challenge to the RSKN, charging it with manipulating the salmonella problem. According to the Union, “the [salmonella] violations by those companies were detected in September-October 2011, but for some reason neither the Russian importers, nor the [Norwegian] manufacturing plants have been notified about it.

“Also, this information was not posted promptly on the website of Rosselkhoznadzor. Thus, the responsible persons have jeopardized the safety and health of Russian consumers, having failed to make timely notification to them of the threat. Unfortunately, the fate of products sold from those Norwegian companies is unknown, and for several months they continued to enter the territory of Russia.

“The Fish Union believes the timing of the information that appeared on the website of Rosselkhoznadzor is not random as it was published on the eve of the meeting of the Norwegian-Russian working group on safety of imported fish products, scheduled for February 13, 2012 in Oslo (Norway). All this gives reason to question the officially declared transparency and openness in the conduct of monitoring activities to ensure the safety of fish products supplied.

“Also puzzling is the situation related to the lack of official notification to the foreign partners, in particular to the Norwegian suppliers of fish products, on the fact that the contracts for the supply of fish between foreign manufacturers and Russian importers are now to be registered and confirmed via the automated Argus system. The change was adopted on the initiative of Rosselkhoznadzor’s head Sergei Dankvert, thereby increasing efficiency and transparency of procedures. Unfortunately, this initiative has not been explained to date to the foreign partners, who continue to request confirmation of contract registration by their Russian colleagues.

“Here we witness attempts to prevent the introduction of yet another initiative in the field of security of products supplied with the application of new control methods. The fact is that Norway planned to install the automatic transfer of information on products supplied to Russia, and to inform Rosselkhoznadzor about all stages of internal control in the foreign enterprises, ranging from cultivation of young fish on the farms to the composition of feedstuffs. The scandal will probably not contribute to the introduction of new technologies.

“The conclusion from the recent events can be only one: the right hand does not know what the left one is doing. And all the efforts of the head of Rosselkhoznadzor aimed at increasing transparency and efficiency of monitoring the manufacturers face fierce resistance from certain groups, both among the employees of Rosselkhoznadzor and the business community. As a result, not only consumers suffer, but also , perhaps intentionally, the very credibility of the supervisor is being undermined. And in the absence of stable rules of the game businesses incur obvious losses.”

In December, the Fish Union charged RSKN with manipulation of the food safety regulations to benefit the largest of Russia’s fish importers at the expense of the domestic fishing industry and smaller-sized importers.The government’s competition watchdog, the Federal Antimonopoly Service (FAS) took the side of the fisherman against the food inspector.

Norwegian Embassy officials in charge of trade did not respond to calls for clarification of the dispute.

At least one Russian fisheries expert, Timur Mitupov, head of the Analytical Centre for Fisheries Information, believes that the import ban, if implemented, would be more serious for Norway than for Russia.“Norway is a major supplier of herring, capelin, salmon and trout to Russia. But in 2011 the Russian fish industry catch of these fish has grown substantially. Therefore, if there is a ban on the supply of the Norwegian fish, then Russia will be able to replace the Norwegian exports through its own catch and through the reallocation of imports from other countries.” Last year, Mitupov said, the domestic catch of salmon (excluding fish farming) came to 520,000 tonnes, up almost 200,000 tonnes per annum over the previous average yearly salmon catch. Herring, he added, is also being caught in large enough volumes by the Russian fishing fleet so as to reduce the requirement for imports.

According to Mitupov, 2011 was the first year in a long time when Norwegian exports of fish to Russia fell significantly. Norwegian export data confirm that while value of the exports of fish to Russia was almost unaffected, in tonnage the volume of fish delivered to Russia fell by 14%, compared to 2010. Mitupov concedes that the salmon imports from Norway cannot be so easily substituted by a bigger domestic catch, by Russian fish farming, or by alternative suppliers. This is because alternative imports are from further away and land in frozen form. Norwegian salmon lands in Russian kitchens in chilled or cooled form. Domestic fish farming is a business of Gennady Timchenko, the oil trader who took over Russian Sea group last year.

The legal status for competing fishing fleets in the Arctic isn’t likely to be settled any time soon. On September 15, 2010 Russia and Norway signed their border delimitation agreement for the Barents Sea. In February 2011, this was ratified by the Norwegian parliament, and the next month by the Federation Council in Moscow. But the sea frontier line is well to the east of the Svalbard zone which the Norwegians have claimed for exclusive fishing around Spitzbergen.

The Norwegian claim to the western area has never been accepted by the Russians, nor endorsed by the international maritime organizations.

Alexander Saveliev, an official at the federal fishery agency Rosrybolovstvo, which supervises the Russian fishing fleets and administers catch quotas, is in favour of import substitution. “Russia will only gain,” he said, “if we get rid of Norwegian salmon imports, as the quality of their products is horrid. They grow fish in cages, feed them with animal feedstuffs and antibiotics. We can easily replace that with wild salmon caught by Russian seamen. Last year they caught 520,000 tonnes, 154,000 tonnes of which was exported, while the imports reached 164,000 tonnes.”

Leave a Reply