By John Helmer, Moscow

There has long been a fear on the Russian side that South Africa will sell as much platinum and palladium as it can mine, threatening the market price of both metals, and leaving Russia holding very large, very secret stocks of dwindling value. From the Russian point of view, that’s not a unilateral sacrifice Russia should accept; nor a unilateral advantage South Africa should be allowed to take.

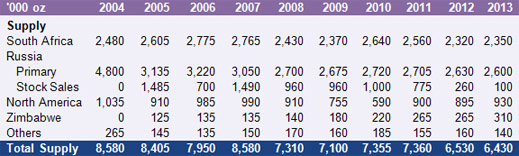

Together, Russia and South Africa (SA) produce almost 90% of the world’s platinum supply (5.7 million ounces); 80% of the palladium supply (6.4 million oz). So there has been a natural inclination for the principal producers – Norilsk Nickel in Russia; Anglo Platinum, Impala, Lonmin and Northam in South Africa – to test the scope for price-supportive cooperation in the market, instead of price-damaging competition. The Russian and South African governments have naturally inclined in the same direction.

In March 2013, the Russian and South African ministers in charge of mining and metals appeared to have agreed, and signed, a “framework of cooperation”. The governments issued no communiques, and released no papers. A single media report, republished many times over, claimed the governments “plan to set up an OPEC-type trading bloc to coordinate exports. ‘It can be called an OPEC’” Russian Natural Resources Minister Sergey Donskoy [top image] said late yesterday in an interview in Durban. ‘Our goal is to coordinate our actions accordingly to expand the markets. The price depends on the structure of the market, and we will form the structure of the market.’”

Susan Shabangu (right), then SA’s mining minister, was reported as saying the idea was “to counter oversupply of platinum, possibly through taxes and incentives. ‘We’re not really controlling the market,’ she said in an interview in Durban. ‘We want to contribute without creating a cartel, but we want to influence the markets.’” Donskoy added: “We are now forming working groups to work out joint actions on this market. There will be a meeting in the summer to discuss mechanisms in detail.”

Susan Shabangu (right), then SA’s mining minister, was reported as saying the idea was “to counter oversupply of platinum, possibly through taxes and incentives. ‘We’re not really controlling the market,’ she said in an interview in Durban. ‘We want to contribute without creating a cartel, but we want to influence the markets.’” Donskoy added: “We are now forming working groups to work out joint actions on this market. There will be a meeting in the summer to discuss mechanisms in detail.”

Not a word has been heard of the “platinum OPEC” since. According to a Norilsk Nickel source this week, “everything is dead there”. Among the Moscow investment and industry analysts who follow the precious metals and Norilsk Nickel, Dinnur Galikhanov of Aton says: “I have not heard anything about it, and do not know if there was any progress in this direction beyond the announcement. Rarely is there anything more than words. In South Africa, right now they have their own problems. They have miners on strike in the platinum mines, so they are bound to have to deal with these problems before thinking about how to organize a platinum OPEC.”

Donskoy’s Ministry of Natural Resources refuses to say what has become of the framework agreement or the joint government working groups.

In South Africa, mining and metals analyst Peter Major of Cadiz says: “from what I know – the PGM [platinum group metals] cartel announcement was wishful thinking — little more than hot air. I am sure it was a South African idea, though possibly it had been planted by the Russians without the South Africans realizing.”

Michael Kavanagh, precious metals analyst with Noah Capital Markets of Johannesburg and London suggests it was the South Africans who initiated the idea. “They are the ones sitting with labour issues, unemployment, mine closures, and perhaps most importantly, the platinum belt has become a hot-bed for the start-up of opposition unions and political parties which want nothing to do with the [ruling party, the African National Congress]. If stability could be brought to the SA mining sector, that would help the ANC a lot.”

In the international market place, there is a consensus that whoever came up with the idea to start with, neither the SA nor the Russian government is capable of creating a market control or influence organization; and together, they cannot stop either price volatility or a price slide. Instead of rising on the announcement that supply might be restricted by agreement, over the past year the price of platinum has gyrated through almost $250 worth of value per ounce, and at the present price of $1,457, the metal is 8% below its level when Donskoy and Shabangu made their announcement.

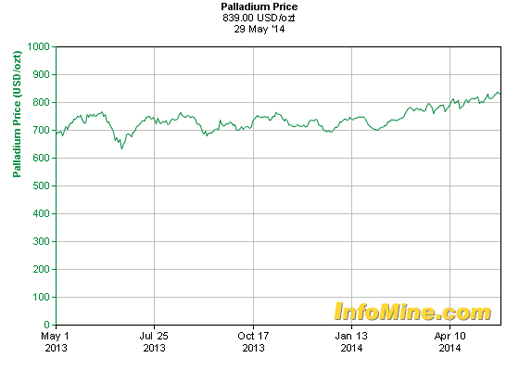

Source: http://www.infomine.com/

Palladium has been more stable, by comparison. It was $767 on March 28, 2013; it is now $839, a gain of 9%.

Source: http://www.infomine.com/

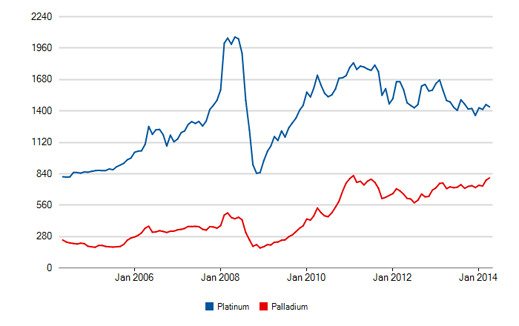

Over the decade, both metals are below their peaks, but still well above their starting points.

Source: http://www.platinum.matthey.com/

Market sentiment towards future pricing of PGM is mixed. According to Major, “my forecast for platinum this year is that we are at the peak right now and the price will head lower from here on. I believe in reversion to the mean. The long-term real price of platinum is $950/ oz, and $400 oz for palladium. Only the South African mine strike is holding it up, in my view. I hope I’m wrong. But I worry I’m right!”

Kavanagh of Noah Capital argues that if prices were to fall to the levels suggested by Major, “there would have to be an offset in the form of a substantially weaker rand/dollar exchange rate to keep the South African miners in business. At the current exchange rate, with Pete Major’s prices, all SA production will cease.”

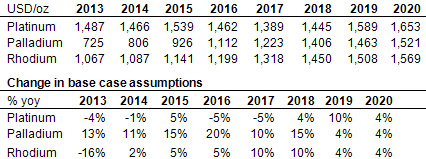

Kavanagh’s price projections also indicate price convergence between platinum and palladium. This is based on trends in the application of the two metals to the manufacture of engine emission controls, and the respective value of the two metals to the automaker.

PGM PRICE PROJECTIONS BY MICHAEL KAVANAGH/NOAH CAPITAL MARKETS

Source: NOAH Estimates

For Kavanagh’s forecasts and Noah Capital Markets research, go to the website.

A report from ScotiaMocatta, a Canadian specialist, issued last November before the current South African mine strike began, was more pessimistic about platinum than palladium. It also sees South African government action influencing the platinum price, and Russian government action the palladium price – without sign of coordination between the two of them.

For platinum, “we expect prices to remain range bound between $1,300 and $1,500/oz, but we would expect prices to react positively if there is further strike action, or continued industrial demand and then as 2014 unfolds we think prices are likely to move back over the 50 week moving average to

trade in the $1,450 to $1,650/oz range.”

For palladium, the price driver is viewed as the size of the state inventory of palladium held by the Russian state stockpile agency, Gokhran. “Sales from Russian stockpiles are expected to wither – stockpile sales had up until recent years filled the structural gap between supply and demand. Once stockpiles sales actually dry up we think that will have a bullish psychological impact on the market. Given the supply deficit and it is a deficit that is not being caused by investment offtake, plus the potential for supply disruptions in South Africa, we feel there is a high risk of prices breaking up through stiff resistance in the high $770-$790/oz area and that could then lead to prices challenging the ground seen in 2011.”

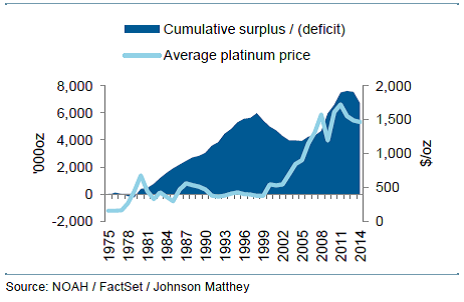

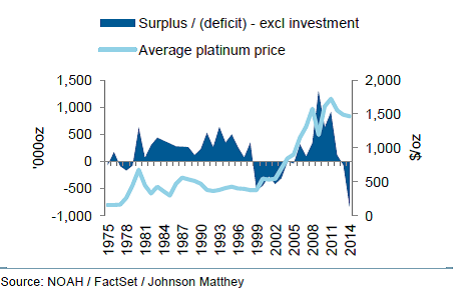

Kavanagh is forecasting downward movement of platinum for the foreseeable future. That’s because he believes, as does the trade, that there is too much platinum in off-market stocks for increasing industrial or jewellery demand, cuts in supply from the SA mine strikes, or OPEC-type manipulation, to counteract the surplus in the shadows. Much of the platinum surplus is beyond government control, contained as scrap in platinum-bearing automotive catalysts waiting to be recycled.

“There is little or no positive correlation between the supply/demand numbers and the metal price. In fact often the correlation is negative or opposite to what one would expect… When analyzing the available data for the three metals [platinum, palladium, rhodium], we find that substantial above- ground inventories of all three metals have been built in the last three decades. We calculate close to 7mln oz of platinum, 11mln oz of palladium and 600koz of rhodium have been produced in excess of industrial and fabrication demand. These inventories are likely in the hands of investors. Investors who, seeing the lack of price action in response to the South African strikes, must be very nervous…With mine supply disrupted, above-ground inventories of PGM’s are being diminished. However, there still seem to be substantial above-ground inventories. In addition, at some stage mine production will resume and there are a number of new mines in the pipeline. Meanwhile users of the metal are actively looking for ways to use it more efficiently, if not eliminate its use. As such we would not be getting over-excited regarding the prospects for metal prices in the PGM space for the time being.”

Kavanagh makes the case that inventories and stockpiles are the dominant price-setting force — supply and demand for new production of the metals are not.

PLATINUM PRICE RISES, BUT SO DO UNSOLD PLATINUM STOCKS

PLATINUM PRICE IS NOT CORRELATED WITH THE SUPPLY/DEMAND BALANCE

There is a similar inverse relationship for palladium between accumulating stocks and rising price.

Reporting by Johnson Matthey of supplies of palladium to the market from mine production and from stockpiles shows that Gokhran, the Russian stockpile agency at the Ministry of Finance, has been steadily reducing its sales since peak between 2005 and 2007.

How much Russian palladium remains in stockpile is one of the secrets the state has been able to hang on to since 1991, and the subsequent privatization and international listing of Norilsk Nickel. As Kavanagh points out, “Norilsk has been producing since the late 1930s. By 1950 it was producing in large volumes. What happened to the PGMs produced between 1940 and 1980? Were they refined or stockpiled in semi-processed form? I have heard suggestions that Russia and Norilsk have mountains of PGMs in mine tailings or semi-processed form that could come to the market if needs be.”

“Large chunks of the world’s production of platinum and palladium have been taken out of the market for long periods of time and yet there has been little or no metal price response. This suggests that either the assessments of supply / demand are wrong or that there are plenty of inventories around to make up for shortfalls in primary supply.

“I would think that the current metal price reaction to supply disruptions would put pay to thoughts South African and Russian officials might have towards forming a PGM OPEC. They would appear to be powerless. Also, one could make a case that Russia and South Africa are in opposition when it comes to PGMs. Primarily Russia produces palladium while in SA platinum dominates the production mix. The two metals have been eating each other’s lunch, or perhaps it’s truer to say that palladium has been eating platinum’s lunch. They are the best substitutes for one another.”

Leave a Reply