By John Helmer, Moscow

In the wake of the lethal Odessa fire on May 2, President Vladimir Putin and Chancellor Angela Merkel agreed by telephone on Sunday afternoon “to take effective measures, including through the OSCE in the first place, aimed at easing tensions in Ukraine. In this connection, Swiss Federal President and OSCE Chairperson-in-Office Didier Burkhalter will arrive in Moscow on May 7.”

This amounts to an invitation for the Swiss to exercise their longstanding neutrality in European conflicts to keep the warring sides apart in eastern and southern Ukraine; prevent the violence; and create the conditions in which a durable settlement between the Ukrainian regions may be negotiated on a new constitutional basis. In short, an international police force.

That’s an option which the Kremlin has been quietly circulating to the European governments for days. The Obama Administration has refused to accept it because the deployment casts doubt on the capacity of the Ukrainian security forces, and restricts the special forces who caused the May 1 Odessa fire. From the American point of view, too, such a European force is exactly what US officials don’t want because it’s – State Department expletives deleted – European.

The F word in Washington mouths is the Eu word in the OSCE’s title – the Organization for Security and Economic Cooperation in Europe. First created between 1973 and 1975, the 34 founding parties to the Helsinki Final Act creating the OSCE were almost all European – except for Turkey, Canada, and the US. There are now 57 treaty states, the additional number resulting from the breakup of Yugoslavia, and then the Soviet Union. The three non-European exceptions haven’t changed – Turkey, the US and Canada.

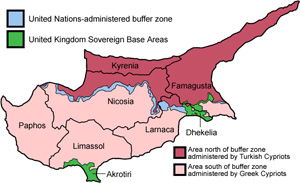

The US continues to keep troops in Europe, by invitation. Turkey is the only OSCE member state to occupy a European state without invitation. Following an invasion of 1974, about 30,000 Turkish forces remain on Cypriot territory, where their presence is unlawful according to successive United Nations resolutions over forty years. The Turkish occupation and partition of Cyprus is armed, financed and supported by the US. It has been justified by both as preventative action to secure the lives and rights of the Turkish-speaking population of Cyprus; and to prevent an earlier putsch against the Cypriot government leading to a union between Cyprus and Greece.

The US continues to keep troops in Europe, by invitation. Turkey is the only OSCE member state to occupy a European state without invitation. Following an invasion of 1974, about 30,000 Turkish forces remain on Cypriot territory, where their presence is unlawful according to successive United Nations resolutions over forty years. The Turkish occupation and partition of Cyprus is armed, financed and supported by the US. It has been justified by both as preventative action to secure the lives and rights of the Turkish-speaking population of Cyprus; and to prevent an earlier putsch against the Cypriot government leading to a union between Cyprus and Greece.

The OSCE is chaired on an annually rotating basis by the foreign minister of one of the member states; the present chairperson-in-office (CIO) is Didier Burkhalter, the Swiss Federal President and Foreign Minister. His OSCE term runs for the calendar year 2014. Next year Serbia will hold the post.

The OSCE headquarters is in Vienna, where a ministerial-level permanent council meets every week. They delegate day to day operations to a secretary-general, and there have been five of them to date – a German, a Czech, a Frenchman and two Italians. The present secretary-general is Lamberto Zannier (right), an Italian.

The OSCE headquarters is in Vienna, where a ministerial-level permanent council meets every week. They delegate day to day operations to a secretary-general, and there have been five of them to date – a German, a Czech, a Frenchman and two Italians. The present secretary-general is Lamberto Zannier (right), an Italian.

His three-year term runs out in July of this year.

“We help bridge differences between states and build trust through co-operation” is the way the OSCE describes its mission today. “With its specialized institutions, expert units and network of field operations, the OSCE addresses a range of issues that have an impact on our common security, including arms control, terrorism, good governance, energy security, human trafficking, democratization, media freedom and minority rights.”

One of the questions Merkel and Putin have agreed to ask Burkhalter to answer on Wednesday is the N word – how neutral can the OSCE be in the present Ukrainian conditions? The question has special sensitivity because of the detention in Slavyansk, in the Donetsk region, of a group of military observers, whose credentials, mission, and status have been widely confused with the OSCE’s civilian operation, the Special Monitoring Mission.

The military men — 4 Germans, 1 Czech, 1 Dane, 1 Pole and a Swede — were detained at Slavyansk on the evening of April 25 (picture left). The Swede was released quickly for medical treatment of his diabetes. The others were released on May 1, after a week of negotiations led by the Kremlin’s special emissary, Vladimir Lukin (picture right).

The credentials of the soldiers to be where they were, out of uniform, doing what they were doing, were not issued by the OSCE, nor did they report to OSCE. They were a military inspection team invited by the government in Kiev, according to a European military inspection protocol known as the Vienna Document of 2011.

The military inspections provided for by the Vienna Document have been designed for cross-border purposes, not for internal conflicts verging on civil war. According to a US government statement in mid-April, “Russia has committed grievous violations of international law, and this is the background against which we are seeking to understand their deployment of troops on the Ukrainian border.”

A week later, the ostensible purpose of the detained Vienna Document men in Slavyansk was to look for evidence of cross-border Russian involvement of the kind alleged by the governments in Kiev and Washington. That foreign field officers without Russian fluency, accompanied by interpreters speaking in Kiev or western accents, could accomplish this after dark in Slavyansk was improbable to the group which detained them. So they called them NATO spies. US and UK newspapers claimed they were operating under the OSCE mandate. None of these claims was correct.

The OSCE explained its mandate in eastern Ukraine on March 21. “The Permanent Council decided in a special session on Ukraine today to deploy an OSCE Special Monitoring Mission of international observers to Ukraine: the mission’s aim is to contribute to reducing tensions and fostering peace, stability and security. Throughout the country, the mission will gather information and report on the security situation as well as establish and report facts regarding incidents, including those concerning alleged violations of fundamental OSCE principles and commitments. It will also monitor the human rights situation in the country, including the rights of national minorities. Facilitating dialogue on the ground to promote normalization of the situation is a further task of the mission.”

“The mandate of the OSCE Special Monitoring Mission forsees [sic] deployment throughout Ukraine, to the east, south and west of the country. Advance teams will be deployed within 24 hours of the adoption of this decision. Initially, the mission will consist of 100 civilian monitors and may expand by a total of up to 400 additional monitors. The monitoring mission will be deployed for a period of six months, its mandate can be renewed for further six month periods by decision of the Permanent Council if requested by Ukraine.”

The special monitors have credentials which have been accepted by the opposition to the Kiev government. On one occasion, a group of special monitors were held for a credential check in eastern Ukraine, but they were not detained.

On April 14, Burkhalter met with the special monitoring mission in Kiev. He announced: “In order to enhance transparency and the level of accurate information about ongoing developments, the Mission in addition to providing reports for OSCE participating States has also started a daily public reporting, he continued.”

So far there have been fifteen such field reports; the last of them runs through April 30. There has been no field report since the Odessa events of May 1.

Initially in charge of the special monitoring mission was Adam Kobiacki, a Polish diplomat who is OSCE’s assistant secretary-general for operations. Burkhalter then announced three appointments. Ertuğrul Apakan of Turkey was named Chief Monitor, with two deputies Mark Etherington of the United Kingdom and Alexander Hug of Switzerland.

The OSCE describes Apakan (below) this way: “Ambassador Apakan has had a longstanding diplomatic career, most recently as Permanent Representative of Turkey to the United Nations (2009 – 2012) and as Undersecretary, Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2006 – 2009).”

Omitted by the OSCE is Apakan’s role in the Turkish military occupation of Cyprus. When the invasion occurred, he was a junior official of the Turkish Foreign Ministry. In 1992, he was appointed Deputy Director General for Cyprus and Greece at the ministry, and in 1996 he was appointed the Turkish ambassador in northern Cyprus. He was there until 2000.

During his term he was one of the principal Turkish officials in charge of the occupation, along with several Turkish generals commanding the military units. According to reports of UN observer missions, European Union investigations, and judgements of the European Court of Human Rights, Apakan’s tenure was marked by systematic violations of most human rights, including ethnic cleansing, confiscation of property, police torture, and in the case of the shooting death of Solomos Solomou in August 2006, murder.

Mark Etherington (picture left), the second of OSCE’s appointments to run the monitoring mission in Ukraine, is described by the OSCE as having been “Team Leader in South Sudan and Team Leader for the UK Government Stabilisation Unit with field missions to various countries on behalf of the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office.”

Omitted by the OSCE is Etherington’s career as a British army officer in the Parachute Regiment until 1991. Thereafter he was assigned to the European Community Monitor Mission during the NATO war on Yugoslavia. While in that post he was also assigned to Kosovo until 1995. In 2003 and 2004, Etherington was the British governor (“governorate coordinator”) in Wasit province in Iraq (picture right), where a battalion of Ukrainian troops was also serving. He then moved to the British command at Basra. From there he was assigned to the British Army’s field headquarters in Helmand province in Afghanistan.

Etherington reported on his career and testified to the lessons he learned in these wars during the official inquiry into the Iraq War. This was initiated in 2009 by the British Government and supervised by the House of Commons. Etherington gave his testimony in July 2010. He complained of American pressure on his operation; “the erosion of consent in Basra”; and the failure of the British command in the “business of what we would call Strategic Communications, the business of influencing the public in theatre to support your aims, to explain what it is you are trying to do and what’s going to happen. This, to me, had been wholly neglected, inexplicably neglected. I just didn’t get a sense we had had a serious stab at this.” That’s not stab in the regular paratrooper’s meaning. The term stabilisation in Etherington’s curriculum vitae is British Army for what the American Army calls pacification.

The second of the deputy chief monitors appointed to Ukraine is also a soldier. This is Alexander Hug, a Swiss national. According to the OSCE, “currently Head of Section/Senior Advisor at the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities, Alexander Hug has worked as Head of Human Rights & Gender Officer for EULEX Kosovo and has held various positions in the Balkans and Eastern Europe.”

The second of the deputy chief monitors appointed to Ukraine is also a soldier. This is Alexander Hug, a Swiss national. According to the OSCE, “currently Head of Section/Senior Advisor at the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities, Alexander Hug has worked as Head of Human Rights & Gender Officer for EULEX Kosovo and has held various positions in the Balkans and Eastern Europe.”

In its latest appointment notice, the OSCE omits that Hug trained as a lawyer, then served as an officer in the Swiss Army. During his military service the OSCE reports elsewhere that he was a regional commander of a Swiss Army support unit for the OSCE in northern Bosnia and Herzegovina. He also served in Kosovo and in Hebron (Palestine).

According to Burkhalter of OSCE, “Ambassador Apakan, Mr. Etherington and Mr. Hug bring a wealth of experience and regional expertise to the Special Monitoring Mission as it enters its full deployment and operational stage. Under their leadership, I trust that the Special Monitoring Mission will contribute to fostering peace, stability and security and to reducing tensions on the ground in Ukraine.”

OSCE spokesmen with the special monitoring mission in Kiev and at the Vienna headquarters were asked whether they were aware of Apakan’s record in occupied Cyprus, Etherington’s military service in the Yugoslav, Iraq and Afghan wars, and Hug’s involvement in Bosnia, Palestine, and Kosovo.

Tatyana Baeva, an OSCE spokesman in Vienna, said her organization was in no position to respond because “it was the Swiss who made the appointment.”

Michael Bociurkiw (right), press officer for the Special Monitoring Mission in Ukraine, describes himself on the internet as “a social media expert and digital influencer”. He also publishes his opinions on Ukrainian politics. “Until now,” he reported on February 21, “there has been little doubt that Yanukovych has been taken his cues from Russian President Vladimir Putin — a man notoriously impervious to opprobrium from the West. Putin is incapable of seeing Ukraine outside his sphere of influence.”

Michael Bociurkiw (right), press officer for the Special Monitoring Mission in Ukraine, describes himself on the internet as “a social media expert and digital influencer”. He also publishes his opinions on Ukrainian politics. “Until now,” he reported on February 21, “there has been little doubt that Yanukovych has been taken his cues from Russian President Vladimir Putin — a man notoriously impervious to opprobrium from the West. Putin is incapable of seeing Ukraine outside his sphere of influence.”

On April 11, a few days before he started on the OSCE payroll, Bociurkiw published in the Canadian edition of Huffington Post: “The [Ukrainian presidential] elections could be seen by Moscow and its backers in Ukraine as a chance to destabilize the situation. If a pro-western candidate makes it past the first round on May 25 that could be reason enough for Russia to engineer the installation of a suitable replacement, even by force. (Kyiv is rife with rumours of a back-room deal between Russian President Vladimir Putin and former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko, which would see the former political prisoner parachuted into the Presidency in exchange for a withdrawal from Crimea).”

Bociurkiw identifies his family as of Ukrainian origin, from the western part of the country. He said he has stopped publishing his opinion pieces on Ukraine since he took the OSCE job. He denies his publications demonstrate a lack of neutrality towards the pro-Russian opinions of Ukrainians in the regions he is monitoring.

Asked whether he and OSCE are aware of the careers of Apakan, Etherington and Hug in military pacification programmes in war zones, and in Apakan’s case, in violation of UN and EU resolutions, Bociurkiw said he himself is not aware of the career records, and promised a written reply. Bociurkiw was also asked whether the OSCE appointees’ military involvements qualify them to be neutral in eastern Ukraine. The responses were not available at publication time.

Apakan’s office was asked the same questions. The reply was: “We do not have the capacity to respond to all individual letters, but we will certainly take them into account in our work.”

Roland Bless, the spokesman for Swiss Minister Burkhalter at the OSCE in Vienna, was asked what the CIO knew of Apakan’s past when he put him in charge of the Ukrainian monitoring mission. “I don’t know”, Bless replied. In Bern today, Burkhalter said through a spokesman: “The Chief Monitor and his two deputies were nominated by their respective state authorities. The appointments followed the usual OSCE procedures. The three dispose of the relevant experiences and qualifications needed to fulfill their mandates in the framework of the Special Monitoring Mission. Special attention was paid to their previous experience in multilateral organizations.”

Leave a Reply