By John Helmer, Moscow

US Government economic sanctions have a hundred-year long history in US statutes and court cases, starting in 1917 when the US was at war with Germany. Trading with the Enemy Act was what the first statute was called. It was clear then who the enemy was, and there was a shooting war in the Atlantic and in Europe to prove it.

Many US wars later, most of them for reasons which turned out to be lies, US Government sanctions have been endorsed by the American courts as a defence against an attacker whose method always included the use of force. But not now.

On Friday April 6, the US Treasury, headed by by Steven Mnuchin (lead image, centre), introduced a new type of economic sanction; read the official announcement. For the first time, the individuals and companies targeted have no record for using force, and there is no evidence of their intention to use it. Instead, they are accused, and by the new sanctions punished, for things which American citizens have the constitutional right to exercise – the freedom of association and the freedom of expression.

The Russian targets of the new sanctions, announced Mnuchin, are proscribed for the full range of economic sanctions because of their association with the Russian government, and because they are Russians doing business in Russia. “The Russian government operates for the disproportionate benefit of oligarchs and government elites,” Mnuchin said, stamping his foot where Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin and C. Wright Mills have famously trod before. “The Russian government engages in a range of malign activity around the globe”. Ergo, a Russian businessman associating with the Russian government and growing rich is a threat to the equitable distribution of income and capital in Russia; ergo, he is a threat to the security of the United States. Never before has Russian capitalism been declared an enemy of American socialism, and forbidden to borrow, lend, own or trade with Americans or the US dollar.

Victor Vekselberg, for example, has been “designated”, according to the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), “for operating in the energy sector of the Russian Federation economy. Vekselberg is the founder and Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Renova Group. The Renova Group is comprised of asset management companies and investment funds that own and manage assets in several sectors of the Russian economy, including energy.”

Mnuchin implies the Russian energy sector is a “malign activity”. For evidence, he says a Russian criminal prosecution is under way of bribery to rig provincial electricity rates in which two Vekselberg company executives have been indicted and imprisoned in Moscow. Mnuchin doesn’t mention the criminal and civil proceedings under way in Russia, and also in New York, involving other Russian energy utilities, whose controlling shareholders include Russians like Mikhail Prokhorov and Leonid Lebedev. Prokhorov’s New York assets and Lebedev’s New York bank accounts and California residence are not malign by the new Mnuchin standard, so they aren’t sanctioned. For their US stories, click for Prokhorov; click for Lebedev.

US lawyers report that until now the courts have been reluctant to accept challenges to the legality of sanctions. But Bruce Marks (right), whose firm Marks & Sokolov LLC has practised in Philadelphia,  Moscow and Kiev for more than twenty years, says some of the latest sanctions have gone beyond the limits defined in the statute and the case law. “The Treasury has gone too far this time in regard to certain persons on the list,” Marks said. “The targeting of these persons appears to be arbitrary and capricious. Those terms satisfy one of the standards US judges say will justify overturning the designation. There’s also no rational connection between the facts and the government’s decision to choose some of these individuals to punish. At a minimum, these individuals have rights to obtain non-classified information from OFAC which formed the basis for the sanctions. On the other hand, some of the others were appropriately put on the list.”

Moscow and Kiev for more than twenty years, says some of the latest sanctions have gone beyond the limits defined in the statute and the case law. “The Treasury has gone too far this time in regard to certain persons on the list,” Marks said. “The targeting of these persons appears to be arbitrary and capricious. Those terms satisfy one of the standards US judges say will justify overturning the designation. There’s also no rational connection between the facts and the government’s decision to choose some of these individuals to punish. At a minimum, these individuals have rights to obtain non-classified information from OFAC which formed the basis for the sanctions. On the other hand, some of the others were appropriately put on the list.”

Marks led the way in the US courts to prosecute Russian oligarchs under the US laws against conspiracy to defraud; his casebook includes racketeering lawsuits involving Oleg Deripaska (Rusal), Vagit Alekperov (LUKoil), Alisher Usmanov (Metalloinvest), and Mikhail Fridman (TNK, Alfa – lead image, between Mnuchin and President Donald Trump). For details of these cases employing the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO), open the archive.

“It’s ironic,” Marks notes, “that in all those cases the US courts refused to take jurisdiction over the Russian oligarchs on the ground that was up to the Russian courts. Now here we have the Treasury Secretary taking jurisdiction from the Russian courts on grounds American judges have always dismissed. Perhaps if the American courts exercise their undisputed jurisdiction in civil cases under RICO, this will positively influence events in Russia through plaintiffs serving as ‘private attorney generals’ just as the statute envisioned.”

Court challenges to sanctions have succeeded in the UK and in the European Union (EU), where the target was an Iranian bank; click to read. In Canada in 2014 there has been the successful case of two Russian banks overturning their sanctions designation because of a mistake by officials in Ottawa who got the names of their targets wrong.

The only British and EU court challenges to sanctions against Russian oil companies and banks have been dismissed. Rosneft and other Russian corporations which have tried to litigate have lost confidence in their own lawyers, as well as in the independence of the courts from political pressure.

In the US there have no court challenges by a Russian since sanctions began with the Ukraine civil war in March 2014. The reason, US legal experts say, is that American judges are very reluctant to challenge the presidential power to conduct foreign, defense and security policy, and to sanction foreigners as threats.

In 2015 the US Court of Appeal and the federal District Court in Washington, DC, issued rulings to spell this out. In one of the cases, a Peruvian, Ferdinando Zevallos, accused of being a drugs trafficker, challenged the legality of OFAC’s sanctions against him. At the time he was in prison in Peru after a drugs conviction there. The second case was an appeal by a Ukrainian company against the blocking of a financial transaction through a US bank with a sanctioned Belarusian oil trader allegedly connected to the Belarus President, Alexander Lukashenko.

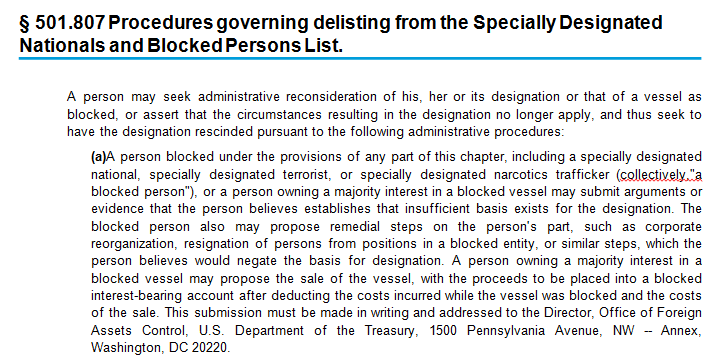

In both cases the US lawyers sued OFAC under the procedure in the US Code known as Section 501.807. This allows sanctioned individuals and organizations to apply to OFAC for disclosure of the files, for a review of the evidence used to justify the sanctions, for a statement of reasons, and for de-listing.

Zevallos’s challenge was rejected by the Court of Appeal in a judgement issued in July 2015. The 3-judge panel ruled that the sanctions decision had not been arbitrary, capricious or an abuse of discretion by Treasury officials. They also ruled that the evidence admissible in court to support the reason given by OFAC includes “third hand accounts, press stories, material on the internet, or other hearsay.”

The judges added they were not required to verify whether the government’s evidence against Zevallos was the truth. Instead, they said they would accept that there was a “rational connection between the facts found and the choice made”, and that there were sufficient grounds for OFAC to have decided as it had done. That Zevallos had already been convicted in Peru of the crimes for which OFAC had designated him for US sanctions was the clincher.

In a second Section 501 challenge later the same year, federal judge Colleen Kollar-Kottelly (right)  dismissed a challenge to sanctions by OKKO Business PE, a Ukrainian company, whose payment of €200,000 through Citibank to UE Belarusian Oil Trading House (UEB) was blocked. “OFAC’s decision,” the judge accepted, “was based on information providing reasons to believe that UEB acts as a clearinghouse for financial, contractual, and web-based transactions on behalf of Belarus’largest petrochemical conglomerate, which in turn is controlled by Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko—an individual listed [sanctioned in 2006] by the President on the Annex to E.O. 13405.” She said the law required her to be “extremely deferential” to the sanctions decision “because OFAC operates in an area at the intersection of national security, foreign policy, and administrative law.”

dismissed a challenge to sanctions by OKKO Business PE, a Ukrainian company, whose payment of €200,000 through Citibank to UE Belarusian Oil Trading House (UEB) was blocked. “OFAC’s decision,” the judge accepted, “was based on information providing reasons to believe that UEB acts as a clearinghouse for financial, contractual, and web-based transactions on behalf of Belarus’largest petrochemical conglomerate, which in turn is controlled by Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko—an individual listed [sanctioned in 2006] by the President on the Annex to E.O. 13405.” She said the law required her to be “extremely deferential” to the sanctions decision “because OFAC operates in an area at the intersection of national security, foreign policy, and administrative law.”

For reason of “the deference,” the judge said, “that must be afforded to OFAC’s interpretation of its own regulations, and the controlling case law, the Court cannot conclude that OFAC’s decision lacked a rational basis.” She added: “it is not the Court’s role to undertake its own fact-finding or substitute its own judgment for that of OFAC.”

“Matters of strategy and tactics relating to the conduct of foreign policy,” according to Kollar-Kottelly “are so exclusively entrusted to the political branches of government as to be largely immune from judicial inquiry or interference…. Accordingly, the Court cannot conclude that OFAC exceeded its statutory authority by continuing to block the funds in question.” Before she took her seat on the federal district court, Kollar-Kottelly was chief judge of the most secret and deferential of the US courts, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court.

US legal experts believe sentiment in Washington is now running so high against Russia, and the evidence required by OFAC so little, it is unlikely any judge would sustain a Section 501 challenge from one of the Russians sanctioned last week.

In Moscow a corporate lawyer comments: “it’s obvious the US Government is playing favourites, protecting oligarchs like Fridman, Prokhorov, and Roman Abramovich, who have very large business interests in the US. This isn’t arbitrary – it’s deliberate US Government policy.”

Russian political analysts comment that it’s now up to President Vladimir Putin to decide whether the sanctions are acts of economic warfare and strike back. Advisors telling Putin publicly not to retaliate, and to seek special deals for selected oligarchs, are led by Alexei Kudrin, a former finance minister sacked in 2011 by then-President Dmitry Medvedev; Kudrin is hoping Putin will appoint him in Medvedev’s place next month.

“I believe,” Kudrin told reporters this week in Moscow, “that with regard to private American business [Russian counter] sanctions are inappropriate, because business brings technology and investment here…I think politicians who are engaged in sanctions and impose sanctions against Russia – in general, that is one story, but business is another.”

US Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner leads then-Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin at the Pittsburgh economic summit conference in 2009.

A critic of Kudrin’s influence with Putin comments in Moscow: “the Foreign Ministry diplomats have achieved nothing in London and Washington. If Kudrin is convinced the economic warfare of our enemies can be negotiated away, as he keeps saying, Putin should send him to be ambassador in London or Washington, and let’s see how he goes.”

Marks says that Russians on the list of oligarchs published by the Treasury on January 30 may be able to persuade the Treasury against designating them in future. For that list, and the story of Mnuchin’s selectivity, read this. “It’s possible to deter OFAC from future designations by providing information on why sanctions would be inappropriate,” Marks advises.

“The individuals who have been sanctioned have rights in US law. But they must make a convincing challenge to a sanction designation already made. To go to court, a designated individual or company must first apply to OFAC according to the Section 501 procedure. This requires a showing of mistaken designation, change of circumstances, or other good grounds, and the arguments must be supported by substantial supporting documentation. To raise the standard of legality on the part of the Treasury, someone on the Russian side must go first.”

Leave a Reply