By John Helmer, Moscow

Euroset, the Russian mobile telephone company, failed at its attempt at its initial public offering (IPO) in London this week. Officially, the company is struggling to absorb the punch, and is blaming the markets, not itself. “Despite the fact that in the investment community there was an increased interest in Euroset,” Euroset’s chief Alexander Malis told a Moscow newspaper, “we decided to postpone the IPO due to volatility in the markets”.

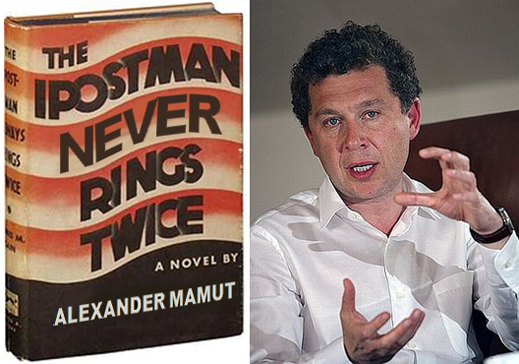

The company’s control shareholder, Alexander Mamut, declined to answer questions today. But he is blamed in the London market for the failure.

“The Euroset IPO was a special case, and shouldn’t be compared to other Russian IPOs in the pipeline,” said the head of research at a major Moscow institution. “The control shareholder [Mamut] wanted to cash out, and that left little of the proceeds of the share sale to go back to the company. Investors don’t like IPOs when the control shareholder is selling so many of his shares. The market asks – why are you cashing out? Why should I buy into the company if you are walking away?”

Euroset was bought by Mamut from the founding shareholders, Yevgeny Chichvarkin and Timur Artemiev, in September 2008. Chichvarkin has since fled to London to avoid Russian prosecution on charges he claims are trumped up to force him to drop his asset. It wasn’t clear at the time of the sale whether Mamut intended to stick with the company, or flip it as soon as he could get a target return on his investment. One month after his takeover, Mamut sold 49% of Euroset to domestic mobile telephone competitor, Vimpelcom.

When the IPO plan was released, indicating that Mamut proposed selling a 35% stake of Euroset, leaving just 15% of the 100% he had started with, it was plain that Mamut was taking the lion’s share of the IPO proceeds for himself, leaving the company’s control to others.

| This was the equivalent of an evacuation alarm for the telephone company’s potential shareholders. |  |

Euroset had started the year valuing itself at $4 billion. Sympathetic analysts of the Russian telecommunications sector, working from slightly different models and projections of the company’s future earnings, put its value at between $3.2 billion and $4.9 billion. The reported revenues for 2010 came in at $2 billion, up 17% on 2009, with earnings (Ebitda) of $274 million growing at a rate of 88%. Net income for the year was $175 million; net debt at year’s end was $273 million. To multiply these results to achieve an average valuation of $4 billion was not the consensus of the Moscow telecommunications sector analysts, however. According to Natasha Zagvozdina of Renaissance Capital on March 15, “we see 10-11 x [times] 2011E[estimated] EV/EBITDA [Enterprise Value/Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization] and 15-16x P/E [share price/earnings] as fair multiples for Euroset, corresponding to a valuation of $2.6-2.8bn. If management can convince investors of its ability to deliver faster revenue growth than 10% in roubles in 2011 and sustain high margins, it could achieve a $3.0-3.8bn equity value, we think.”

The answer to that hypothetical has turned out to be a categorical no.

By the time the IPO prospectus was in the market place and the roadshow had begun at the start of this month, the share pricing had been reduced by 30%, and the company valuation was down to a range of $2.7 billion and $3.3 billion. Mamut has been targeting cash off the table of between $945 million and $1.2 billion. The company proceeds from the parallel share sale were to have been between $140 million and $171 million – about 15% of Mamut’s take.

When the sun rose over London at the start of this week, the underwriters were already sweating — Alfa Bank (associated with Vimpelcom under Mikhail Fridman’s control), VTB, Credit Suisse and Goldman Sachs were having trouble with their Euroset sales pitch. “The business model wasn’t convincing,” said one source. “There is strong competition in the [Russian telecommunications] market, and the growth prospects were too optimistic.”

One of the rivals of the underwriters in the London market put the problem this way: “Issuers are being reminded that funds don’t want expensive paper any more. Russian IPO’s are high risk for the buyer, as the after-market performance shows in almost every case. Many long-only funds don’t bother now, and the hedge funds are less active than they used to be. It’s a more healthy and disciplined approach. Russian sellers have to get used to it or stay at home. No one is insisting on big discounts, just reasonable expectations on valuation.”

An international figure who has dominated large Russian corporate transactions for more than a decade says he sees a pattern of oligarch exits under way, but at a pace and dollar volume which is unprecedented. He claims that Russian share prices are being manipulated upwards, in order to serve as higher-value collateral for loans to buy offshore assets. “Watch the net private capital outflow figure”, the source recommends. According to the Central Bank reports, the first-quarter outflow was $21.3 billion; that’s less than the previous quarter, when the private capital outflow was $35.3 billion. The first-quarter outflow for the first quarter of 2010 was $14.7 billion; for the same period of 2009, it was $35 billion.

Mamut, who lives in London, has been buying into UK shares; very recently into the diminutive HMV, the music retailer, which has a current market cap of ₤45 million. Mamut is also reported to have said he wanted the cash from the Euroset IPO to buy into the Nomos Bank share sale, which is following in the London market later this month. In that transaction, it is suspected the Czech shareholding group PPF is cashing out most of its 30% stake. The price range for the Nomos IPO has been moving upwards since the marketing began in London, and if Mamut is after a large shareholding, it is likely to cost him between $100 million and $500 million.

The Moscow analyst for a major Asian group believes Mamut’s avarice was part of Euroset’s problem, but that Euroset’s failure isn’t a bellwether for the Russian IPOs to follow: “It appears that the management has made very aggressive growth forecasts for the entire business such as reaching 50percent market share by 2015. It appears that the placing syndicate took most of the [forecasts] at face value, which investors naturally did not agree on. I would argue that the failure this time has to do again not with some country-wide discount, but simply with the management and the banks – the latter’s performance was not adequate and the former were too greedy. Also, Mamut wanted a quick return, and he probably had a number in mind, which pushed the management to raising their forecasts so aggressively.”

Leave a Reply