by John Helmer, Moscow

@bears_with

When the previous piece on the Russian art market was published early this week, an Anglo-European art critic didn’t like the independent direction this market is now forced to take. He was also angry that his personal animus towards President Vladimir Putin, the Russian army, and the war against the US and NATO in the Ukraine was quoted. “You sound like a Putin stooge”, he added.

The source is an Englishman working in Geneva named Simon Hewitt. He is emphatic in belittling the quality of Russian painters compared to their French counterparts, and also the Russian galleries, entrepreneurs, and promoters now trying to build the Russian art market – compelled for the first time in their history to be independent of foreign aesthetics and the business of the art trade; that’s Anglo-French aesthetics, Franco-American business,* and the Russian oligarchs dependent on them.

Hewitt, who has been employed to follow the Russian art auctions of Christie’s, Sotheby’s and MacDougall’s, has now become a Russia hater. “I don’t expect to be back in Russia,” he has said, “until the war is over. I imagine that the Russian army will eventually vote with its feet as it did in 1917, but my guess is that won’t be for another 18 months or so.” Hewitt’s once measured assessments of Russian painting since 2014 have been transformed into a political and military ideology, the object of which is the defeat of Russia in the war, and its collapse into another revolution.

The capitulation of Russian culture to its US and European masters is what this ideology requires – and the recapture of the Russian art market by the triad, the name which Russian art experts give to Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and MacDougall’s.*

In the history of the French artist Claude Monet’s life and art, there were almost no Russians to speak of.

An exceptional one, the artist Wassily Kandinsky, saw one of Monet’s series of haystack paintings in a show in Moscow not long after the first exhibition of them in Paris in 1891. “For the first time I saw a picture,” Kandinsky said. “That it was a haystack, the catalogue informed me. I didn’t recognize it…Painting took on a fairy-tale power and splendour. And albeit unconsciously, objects were discredited as an essential element.” Kandinsky, one of the founders of abstractionism in Russian art, saw Monet’s picture as a non-figurative creation of colour, line, shape.

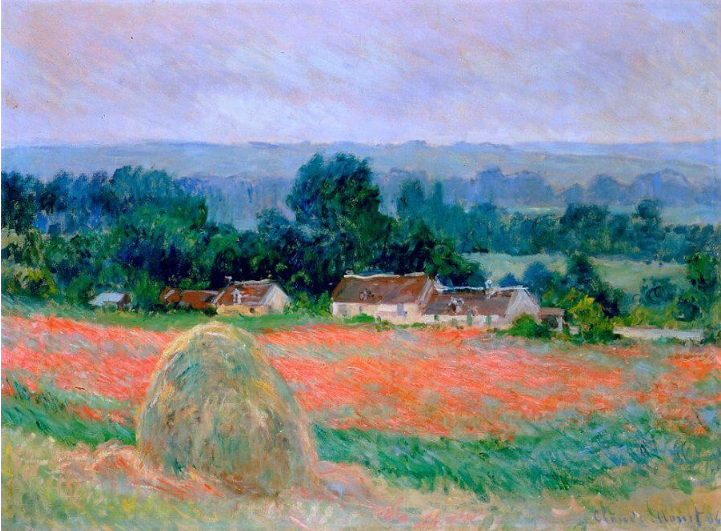

Several years later, Sergei Shchukin, heir to a Moscow industrial fortune, bought one of a series of canvases Monet had been painting in 1899 of London around the Savoy Hotel, the Thames, Houses of Parliament, and the nearby bridges. Shchukin’s wife told him to return the picture because she didn’t like the coloured, shapeless smoke, fog, water, forms, and sunless skies. The thirteen Monet paintings which Shchukin kept – until the collection was expropriated by the state in 1917 – were all figurative. His Haystack at Giverny, painted in 1886, was one of the first of very many Monet painted before Kandinsky saw them a decade later. Shchukin’s wife preferred recognisable objects in the landscape for the decade before Kandinsky preferred abstraction.

This is an obvious matter of aesthetics and taste; it is also a well-known part of the history of modern art inside and outside Russia before the Bolsheviks and the Soviet state cut the money and market nexus, and embarked on revolutionizing the intrinsic value of art.

The telling point now is that in the conditions of war – existential defence for Russia, as this website has been reporting for more than a decade — it is now possible, even required for Russians, and for everyone else exercising their aesthetic principles and personal tastes, to look again at the pictures and compare their intrinsic values – without the rigging of the money market.

In Monet’s time that was arranged by a handful of Paris dealers and a large volume of American money flowing into the Paris market for the first time. Since 2012, when the short history of the semi-annual Russian Art Week auctions began in London, this has been arranged by Christie’s, Sotheby’s and MacDougall’s channelling a large volume of money from the Russian oligarchs and other wealthy Russian businessmen exporting their capital to foreign havens, free ports, and the walls of their offshore residences.

In short, what there is now, because of the war, is a revolutionary condition for the intrinsic value of Russian art — at home now because there is nowhere else.

Here then – on February 23, the Russian holiday known as Red Army or Defender of the Fatherland Day — is an invitation to readers to experiment with their eye, their wartime eye, in looking again at paintings of haystacks.

Monet’s Haystack at Giverny, painted in 1886, was one of his first to depict haystacks. It was bought by Sergei Shchukin for his Moscow collection; it is now in the Hermitage, St. Petersburg.

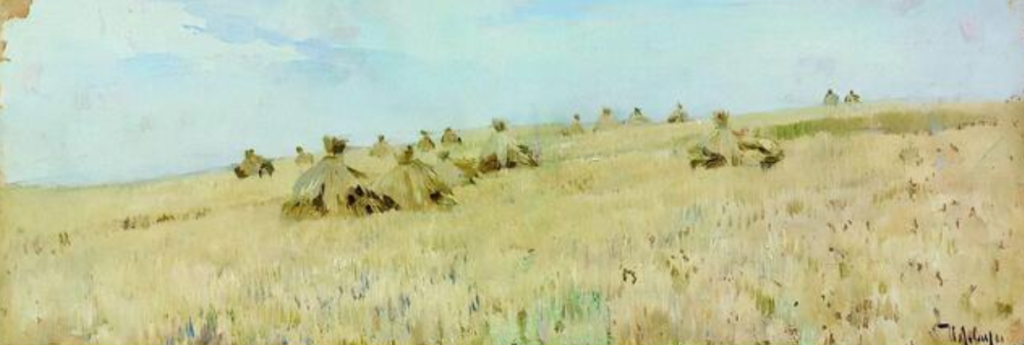

Viktor Vasnetsov, Haystacks, painted in 1890.

Alexei Savrasov, The end of the summer on the Volga, 1873 (Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow)

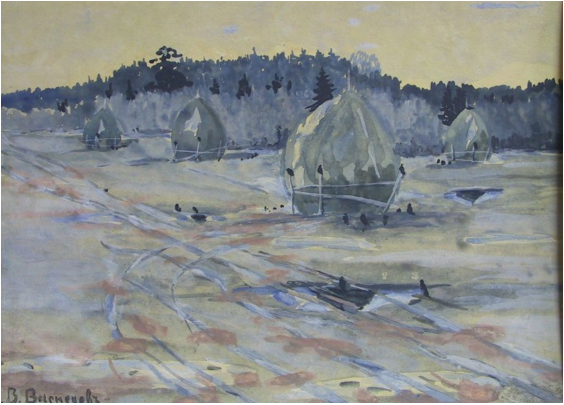

Isaac Levitan’s Haystacks, 1887.

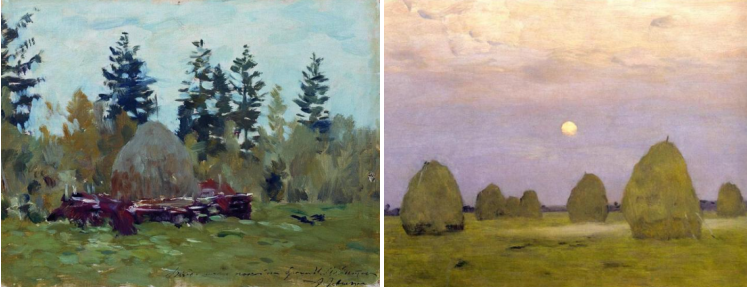

More Levitan Haystacks – above left, 1894; above right, 1899. Below: four undated pictures by Levitan in Russian state galleries.

Levitan, Hay-making, 1900 (Tretyakov Gallery). Levitan died on August 4, 1900.

Looking at these pictures, what do you see? The old Russian national idea or a new one? Orthodoxy, Autocracy, Nationality? National liberation? Or yellow – the sun in Provence, the Romanov flag, or the colour of xanthopsia and cowardice?

The price for these continues to go up.

[*]Christie’s auction house is owned by the French businessman, Francois Pinault; Sotheby’s is owned by Patrick Drahi who is French and Israeli. Because they are private businesses, they don’t publish audited financial reports, but issue press releases instead. In 2023 Christie’s reported its sales revenue had fallen 26% from the year before -- $8.41 billion down to $6.22 billion. Sotheby’s reported its sales revenue came to $7.9 billion, down marginally from $8 billion in 2022. “We are rigorously following the present sanctions and complying with any regulations put in place,” Sotheby’s has announced. Christie’s has said “politically exposed persons, and those with a connection to a sanctioned or other high-risk jurisdictions, are also subject to enhanced due diligence.” In February 2023 federal prosecutors in New York issued subpoenas for auction house records in an investigation of Russian art dealings. MacDougall’s was established in London and Moscow by William MacDougall and his wife, Catherine; William died in August 2022.

Leave a Reply