by John Helmer, Moscow

@bears_with

A London barrister named Michael Mansfield (lead image, left) and solicitor Irene Nembhard (top right) have moved one step closer to claiming a multi-million pound payment from the British Government on their allegation that the British intelligence and security services had been negligent in protecting Dawn Sturgess from a Russian state assassination attack in 2018. The allegation was dismissed in a coroner’s court ruling last December. But this will now be reviewed by a High Court judge in a hearing planned to start in July.

The calculation of the lawyers is that the evidence of the Novichok nerve agent, of the Russian assassination plot against Sergei and Yulia Skripal (top left and centre), and of the cause of death of Sturgess is so secret, and also so false, the British Government will prefer to pay the lawyers their bounty, rather than let a High Court judge hear the evidence in open court and expose the truth.

There has been no court test to date of the British government’s narrative of what happened to the Skripals in Salisbury town centre on March 4, 2018; and then to Sturgess at a flat in nearby Amesbury on June 30, 2018; Sturgess died in Salisbury Hospital on July 8, allegedly of the same Novichok poisoning from which the Skripals have recovered. The inquest into the cause of her death has been repeatedly postponed and is unlikely to be held.

The Skripals are being held incommunicado: Yulia Skripal has not been heard from since July 24, 2018; Sergei Skripal not since June 26, 2019. London lawyers now say the Skripals may be called as witnesses to testify in the High Court.

In papers filed in the Wiltshire Coroner’s Court late last year, Mansfield and Nembhard said they were representing the family of Dawn Sturgess and also of Charles Rowley, her partner at the time of her death, and the renter of the flat in Amesbury where British agents claim to have discovered Novichok in a fake perfume bottle. That discovery wasn’t made or announced until almost two weeks after Sturgess and Rowley were taken to hospital. Sturgess showed no life signs on her arrival at the hospital; she was maintained on life support in the intensive care unit of the hospital until this was cut off on July 8. No hospital witness has come forward to testify about her condition or treatment.

Rowley’s press interviews have been vague, inconsistent, self-contradictory, and evasive on where the perfume bottle was found, by whom; and when. He and the police have been unable to explain how the perfume bottle on his kitchen table and the package in his kitchen waste bin did not turn up until July 11; that was twelve days after Rowley and Sturgess were taken to hospital; and three days after Sturgess’s death certificate was signed; her lawyers are keeping the cause of death entry on this document secret.

According to Wiltshire Senior Coroner David Ridley, no blood sampling of either Sturgess or Rowley at the hospital identified poisoning by a nerve agent; the hospital toxicology reports, also kept secret by the lawyers, identified criminal Class A drugs (heroin, methadone). Ridley has reported he is unsure when Novichok was identified, except that the timing was not until “approximately 2 days later” (emphasis added) – that is, after the alleged police discovery of the perfume bottle, its package and wrappings.

It is essential to Mansfield’s and Nembhard’s case for British government compensation that the paramedics, Salisbury Hospital nurses and doctors, the Wiltshire police, the Secret Intelligence Service, and Ministry of Defence chemical warfare personnel were negligent in failing to detect Novichok. Mansfield, who is known at the Bar for tactics of maximising publicity around his cases, requires secrecy around the evidence. In their defence against a negligence claim, so do the paramedics, hospital and police personnel.

Both groups now rely on the statement to the House of Commons by then-Prime Minister Theresa May on September 5, 2018, that “the police have today formally linked the attack on the Skripals and the events in Amesbury – such that it now forms one investigation.” “There is no other line of inquiry beyond this,” May added, revealing for the first time that the government had found the weapon which had escaped the police and military investigation until then. “There is no evidence to suggest that Dawn and Charlie may have been deliberately targeted, but rather were victims of the reckless disposal of this agent. The police have today released further details of the small glass counterfeit perfume bottle and box discovered in Charlie Rowley’s house which was found to contain this nerve agent. And the manner in which the bottle was modified leaves no doubt it was a cover for smuggling the weapon into the country, and for the delivery method for the attack against the Skripals’ front door.”

Left: Dawn Sturgess. Centre: Sturgess is removed from home to an ambulance by two Great Western Air Ambulance paramedics and (in blue uniform) a Southwest paramedic; image from ITV news film shot at the scene. Coroner Ridley has reported: “Paramedics were tasked to attend an unresponsive female at a property in Amesbury (approx. 8 miles north of Salisbury) – they arrive at 1025. The unresponsive female (Ms Sturgess) is taken to Salisbury District Hospital.” The case notes of the paramedics and the attending doctors at the Emergency Department and Intensive Care Unit of Salisbury have revealed to the coroner and Sturgess’s lawyers that Sturgess displayed no life signs before or after admission; diagnosis was toxic drug combination or overdose. Right: Charles Rowley. He did not follow his partner to hospital. Apparently in fear of the police, Rowley, a recovering heroin addict on methadone replacement medication at the time, spent the next six hours elsewhere. According to Ridley, “paramedics attend the same address in Amesbury shortly after 1820 this time to help Mr Rowley who although is conscious is behaving oddly.”

One consistency in Rowley’s record to date is his hope to make as much money out of telling his story as he can. “Novichok poison victim Charlie Rowley plans to sue the Russian state for a six-figure payout,” the Daily Mirror reported on September 21, 2019, a fortnight after the prime minister’s statement to parliament had alerted Rowley and a Glasgow injury compensation lawyer. “Mr Rowley – who lost his girlfriend Dawn Sturgess and was in a coma for two weeks – has hired top injury lawyer Patrick Maguire. Mr Rowley said: “This has affected my life in a huge way. I want justice.”

Weeks later, Maguire appears to have been replaced by Nembard and Mansfield; Maguire did not respond to questions about the case.

Solicitor Nembhard of the London firm of Birnberg Peirce has confirmed that she and Mansfield are acting in the compensation case for both the Sturgess family and Rowley. Mansfield and Nembhard have converted Rowley’s £1 million pound press announcement against Russia last September into a much larger payoff from the British government. Since they have told the Sturgess family and Rowley there is no chance of winning money from the Russian Government, the only prospect Mansfield and Nembhard have held out is to pursue the allegation that the British authorities had failed in their duty of care to the public; and that following the alleged Russian attack on the Skripals, they compounded their negligence by failing to recover the Novichok bottle before Rowley and Sturgess found it.

Mansfield and Nembhard opened this claim in papers submitted to the Wiltshire Coroner’s Court last October. The lawyers refuse to release them, but they have been excerpted by Coroner Ridley in his ruling of last December. The lawyers demanded the coroner uncover the evidence they want for their claim.

It was the coroner’s duty under UK and European law, they argued, to broaden the scope of his investigation into the cause of Sturgess’s death to include what the Russians had done, and what the UK authorities ought to have done but failed to do. The lawyers intended the innuendo that the coroner would find evidence of advance knowledge of the alleged Russian assassination and nerve agent plan, not only on the part of British intelligence agents, but of Sergei Skripal himself. Mansfield’s threat was to compel Ridley to order Skripal into court.

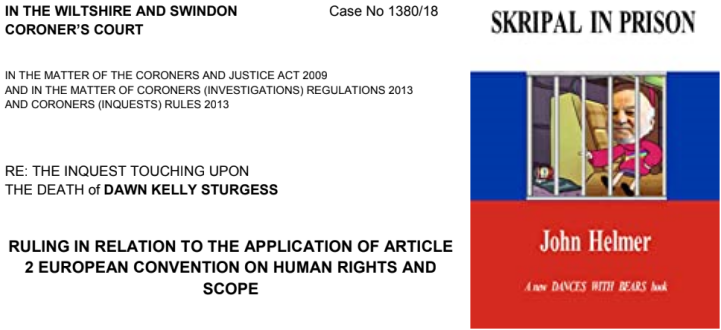

On the recommendation of the Home Office, Ridley dismissed this line of argument in his ruling of December 20 last. For that story, read this. For the full text of the ruling text, click.

The Ridley document (left) is the only presentation of evidence in the entire two-year record of the Skripal case to have been lodged in a court of law; until the High Court opens its hearing shortly, the veracity of the government’s evidence, which Ridley says he has accepted, has not been tested. For the truth test of the evidence so far, and the efforts of the British government to prevent a court test, read the book (right).

The legal issues support Mansfield’s and Nembhard’s pitch to the Government Legal Department (GLD) at the Home Office. To them the lawyers are signalling that, if the High Court agrees and orders the coroner to admit the broad scope of evidence in the case, they will require witnesses to testify from the Metropolitan Police, the Secret Intelligence Service, Salisbury Hospital, and the Skripals themselves. They will be cross-examined painstakingly, runs the lawyers’ threat, to reveal how much of what happened to the Skripals on March 4, 2018, was known in advance, along with what happened to the Novichok weapon between March 4, when it was first used against the Skripals, and June 30, when Sturgess and Rowley sprayed it on themselves – if any of that happened at all.

If the extent of this evidence is not what the Home Office wants to see aired in public for the first time, then Mansfield and Nembhard will require a compensation settlement. “If the aim is to pressure the GLD [Government Legal Department] to settle a compensation claim,” comments a London lawyer, “then this will be done behind the scenes through correspondence and discussions with the GLD. I don’t think it will become apparent in any procedural step.”

BRITISH TROIKA IN CHARGE OF THE STURGESS CASE COMPENSATION & COVER-UP

Left: Sir Jonathan Jones, head of the Government Legal Department. Centre: Priti Patel, Home Secretary. Right: Sir Mark Sedwill, former MI6 agent (Cyprus, Middle East) and currently National Security Advser and Cabinet Secretary.

Before Mansfield and Nembhard can get that far, though, they must first keep secret what they are doing; and then make as public as they can their threat to expose the evidence and the Skripals. The first step was their appeal in January to the High Court to overturn Ridley in a judicial review. That has now succeeded.

Nembhard refuses to say the High Court has agreed to do this, though last week she tipped off a London newspaper which has been active in fostering the same allegations as Mansfield and Nembhard now want the High Court to review.

This week Mansfield refused to confirm the official notice of judicial review, claiming “the professional rules here preclude me from speaking to the press about any case in which I am currently involved. I have passed your request to my Instructing solicitor.” Mansfield also refuses to disclose who his instructing solicitor is, so his reply was intended to block investigation. Mansfield’s clerk, Del Edgeler, also refused to identify the solicitor for the same reason. Edgeler is listed at UK Companies House as running a company now facing strike off for failing to disclose the required records and accounts.

Coroner Ridley said Wednesday through a spokesman in Salisbury “the Coroner is under no statutory obligation to provide press releases, updates or running commentaries on cases in which he is involved.” He acknowledged the judicial review is now under way and that the Administrative Court Office has assigned it the case number CO/1079/2020. In London yesterday, court clerks refuse to say when the court hearing is due to open or the name of the presiding judge. Mansfield and Nembhard have let the press know they believe the first hearing will last two days and will be scheduled for July. Two days are too few to introduce witnesses, but long enough for Mansfield to get the judge’s agreement to call them.

A London lawyer adds: “In due course there will be pleadings lodged with the court. These aren’t public in the sense that they are published but it is open to the media and other third parties to make applications to the court for disclosure of material referred to in court. At the full hearing of the judicial review, yes, witnesses can be called.”

Ridley (right), a provincial solicitor before starting as a deputy coroner in Wiltshire county, has never handled a major national or international case before. On advice from government lawyers in London and the police, he has repeatedly postponed the inquest into Sturgess’s death. It is likely, he announced in December, that no inquest will ever be held, and that instead a state commission of inquiry may be appointed in several years’ time. That will be decided by National Security Adviser Sir Mark Sedwill and Prime Minister Boris Johnson.

Blocking a court hearing of the allegations of a Russian assassination scheme and Russian manufacture of Novichok, and preventing the Skripals from testifying in court, have been British government objectives since the start of Ridley’s inquest. In his ruling of last December, he had rejected the possibility of calling the Skripals as witnesses. Instead, he claimed the two alleged Russian assassins should be called, despite British Government acknowledgement this will not happen. Ridley was also told by the GLD to restrict his investigation of the cause of Sturgess’s death as narrowly as possible.

“It is my view,” Ridley wrote last December, “that matters such as why Mr. Skripal was living in Salisbury, Wiltshire, and what he was doing insofar as any involvement with UK or other intelligence agencies falls outside the scope of a Jamieson Inquest. My preliminary view is that such matters could potentially fall within the scope of another investigation, but that they fall outside the scope of a Coroner’s Inquest being conducted in England and Wales having regard to the current legal requirements of an inquest.”

The difference in British law between the restricted “Jamieson inquest” and the much broader “Middleton inquest”, or “Article 2 inquest”, as Mansfield is demanding, is spelled out here.

Ridley admitted that lawyers for the Home Office had told him, and he agreed, there should be no jury for the inquest. Ridley also accepted the government’s recommendation that “the scope should not include questions as regards who was ultimately responsible for Ms Sturgess’ death and/or the source of the Novichok.”

Mansfield and Nembhard began their compensation case by telling the coroner that Article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights creates the duty on the part of the UK Government to prevent foreseeable loss of life. According to their document quoted by Ridley in his ruling, the British knew in advance the Russians were planning assassination operations in the UK, and that Sergei Skripal was a potential target. If that much was confirmed, then the authorities continued to have the duty to prevent the Novichok weapon from threatening others in the Salisbury area, and ultimately Sturgess and Rowley.

“The first reason that the Article 2 procedural duty is triggered in this case,” according to Mansfield, “is that the death was caused by state agents, namely by the two GRU agents who attempted to assassinate Sergei Skripal in Salisbury using a highly dangerous nerve agent. In addition, the state was otherwise responsible for the death, in that Russian state officials commissioned and organised the attempted assassination.”

“The movements of the 2 Russian suspects in the UK and the question of whether they may by any act or omission have caused or contributed to Ms Sturgess death should be explored.”

“The additional issues” Mansfield told Ridley his inquest should investigate through witness testimony and cross-examination he proposed to conduct himself, “are: Who was responsible for Ms Sturgess’ death…Whether members of the Russian state were responsible for the death… The source of the Novichok that killed Ms Sturgess. Whether appropriate medical care was given to Ms Sturgess…[and] how the Novichok came to be in Salisbury.” Mansfield’s last point foreshadows questions in court for government officials to explain why UK visas were issued to men known to be GRU agents; the surveillance record of their movements when they passed through Gatwick Airport, stopped in a hotel in London, and then took the train to Salisbury. The evidence of their movements in Salisbury, including proof they failed to reach the front-door handle of the Skripal house which, allegedly, they sprayed with Novichok, would also be exposed in court.

British border surveillance images of accused assassins, Alexander Petrov (Alexander Mishkin, left) and Ruslan Boshirov (Anatoly Chepiga, right), passing through Gatwick Airport border control, carrying at least two Novichok spray-bottle weapons, on March 2, 2018. The evidence has been tampered with: “either the date and the exact time were overlaid on the image, or the staff of the Russian GRU learned to walk simultaneously - but their images are captured in two different photographs” – Russian Foreign Ministry spokesman. For more evidence of official evidence tampering, read this.

London lawyers believe Mansfield’s bid to expose this evidence in the High Court will be fiercely resisted by the government lawyers. “Judicial reviews are open proceedings,” said a High Court source, “but in certain, rare circumstances applications can be made for various restrictions ranging from reporting restrictions, anonymisation of judgments all the way through to in-camera proceedings and closed judgments. I would expect the proceedings to be public and think the scope for secret evidence will be very limited. The judicial review is simply to decide whether the coroner’s decision to limit the scope of the inquest was lawful. I can’t see the relevance of any secret evidence that might exist to this issue.”

Mansfield’s reputation at the Bar is that of a skilful exploiter of media publicity in his cases. In order to win this case in the High Court, he must excite press speculation of new secrets to be exposed, and the appearance of the Skripals as witnesses. At the same time, lawyers familiar with the case believe Sturgess was dead on arrival at the hospital and only later selected as the corpse MI6 and the Metropolitan Police required for the discovery of Novichok and the perfume bottle weapon a fortnight later.

“To win the money,” the source believes to be Mansfield’s strategy, “you must push at the threat to reveal the evidence of what isn’t true while concealing the evidence of what is true.”

Leave a Reply