By John Helmer, Moscow

@bears_with

It’s unlikely that when they were alive, Sergei Skripal (lead image, left) and his daughter Yulia Skripal (right) read Enid Blyton.

The paratroop and military intelligence training which Sergei Skripal received prepared him for Afghanistan, Malta, and Spain. By the time he reached England in 2010, he wasn’t undercover, and didn’t need to pretend to having read the Blyton books as a boy. By then too Blyton had been dead for more than forty years, and her books condemned in fashionable English circles as sexist, racist, paedophilic, and sadistic; although Blyton’s prejudice against foreigners has returned to fashion recently. Her taste for playing tennis in the nude did not suit the Skripals or the retired policemen neighbours in their Salisbury block.

Blyton’s books weren’t translated and published in Russian until after Boris Yeltsin became president. The first of her Secret Seven series didn’t appear in Russian until 2015. By then Sergei was 64 years of age; Yulia was 31.

In March of this year, the first of the seven Skripal secrets began to slip into the public prints when Adam Chapman (lead image, centre), a lawyer who was on sabbatical from his London office at the time, was appointed by the British government to represent the two Skripals as their legal representative. The official announcement of his appointment appeared on April 4. For the first time since March 4, 2018, when the front door-handle of their cottage was attacked, and Skripal and his daughter collapsed in the middle of Salisbury town four hours later, it appeared they had recovered their voice and their freewill.

Except that Chapman refuses to speak for the Skripals; to acknowledge that he has been instructed by them to be their lawyer and that he has seen for himself that they are alive.

On July 15, in Chapman’s first public appearance in a London courtroom on behalf of the Skripals, he was asked a question by Lord Anthony Hughes, the judge chairing the public inquiry into the alleged Novichok attacks by Skripal’s former military service. Did he have anything to say to the court for Sergei and Yulia Skripal, Chapman was asked. “Nothing”, Chapman replied, shrugging his head. That was the second of the seven Skripal secrets to slip out.

Chapman’s reticence on behalf of his clients is uncharacteristic. He had been voluble when he was named The London Times Lawyer of the Week. “Acting for lawyers”, he began a newspaper interview in October 2014, “can bring its own particular challenges and I feared it would be like trying to herd cats. Thankfully, that was a slight exaggeration.”

On April 6 Chapman was asked to clarify his representation of the Skripals. Chapman wasn’t exactly the first legal representative of the Skripals in a London court. On March 20, 2018, Vikram Sachdeva QC appeared to be speaking for them in the Court of Protection of the High Court. But at the time they were reported to be “under heavy sedation” in Salisbury District Hospital.

According to a hospital doctor testifying to the court, “Mr Skripal is heavily sedated following injury by a nerve agent. b) Ms Skripal is heavily sedated following injury by a nerve agent. c) Mr Skripal is unable to communicate in any way. d) Ms Skripal is unable to communicate in any meaningful way. e) It is not possible to say when or to what extent Mr or Ms Skripal may regain capacity.” The witness, whose identity the judge kept secret, identifying him only as “ZZ Treating Consultant”, also told Justice David Williams: “The hospital know little about either patient or what they might have wished.”

The doctor and witnesses from the Home Office, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, and the Porton Down chemical warfare centre were not cross-examined or their evidence checked by Sachdeva, purportedly acting for the Skripals. Much of the evidence that has subsequently come to light, including statements by the Skripals, have suggested the doctor’s and the hospital’s claims were misleading or untrue. Read the book for details.

Source: https://www.judiciary.uk/

In his ruling of March 22, 2018, Justice David Williams concluded: “The precise effect of their exposure on their long term health remains unclear albeit medical tests indicate that their mental capacity might be compromised to an unknown and so far unascertained degree.”

The London judge in that case ruled that if not for the fact he had been told they were unconscious in hospital, “the Skripals would be likely to want to support the work of the international body set up by international law knowing that its processes are unimpeachable, it is entirely independent, that the results of its enquiry would potentially be beneficial to the criminal investigation, confirming the nature of the attack and the substance used; assistance in bringing to justice those responsible; identifying those who carried out the attack. They would want to support the UK Government in taking steps on the international plane to hold those responsible to account.”

Williams claimed that when he began his court proceeding on March 20, 2018, he was told by lawyers for the government that the hearing “should be heard in private because of the potentially sensitive nature of the evidence and the need to protect Mr and Ms Skripal and other people involved in the proceedings.”

Sachdeva told the court he had not contacted the Skripals’ family or the Russian Embassy in London. But he knew the Embassy had already announced that it had delivered to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) “the request it had received from Viktoria Skripal to provide information on the condition of her relatives”. The FCO replied to the Embassy on March 11 that “Yulia Skripal remains in a critical, but stable condition in intensive care after being exposed to a nerve agent. As Sergei Skripal is a British citizen we are unable to provide information on his condition to the Embassy”.

Ten days later, according to the judge’s record, “Mr Sachdeva QC also noted that in this case at present it did not appear practicable or appropriate to seek the views of others who might be interested in the welfare of Mr Skripal (his mother perhaps) or Ms Skripal’s (perhaps a fiancé).” The judge added that he had been told by a government witness “neither Mr Skripal nor Ms Skripal appear to have relatives in the UK although they appear to have some relatives in Russia. The SSHD [Secretary of State for the Home Department] have not sought to make contact with them.”

Sachdeva was asked by telephone and email to clarify the difference between what he told the court, what the FCO told the Russian Embassy, and what was public knowledge of the Skripals’ family concerns. Sachdeva refused to answer.

Sachdeva didn’t see Sergei or Yulia Skripal. Sergei has not been seen in public since the day of the alleged Novichok attack. He has not been heard on the telephone by his family members since June 26, 2019. Yulia was last seen in a British and US-directed interview at a US bomber base in May 2018; her last telephone call was heard on November 20, 2020.

On March 25, this year, a new London court was informed the Skripals were actively supporting a British government inquiry into the nature of the attack they had reportedly suffered and those responsible. That inquiry is headed by Lord Hughes, a former Appeal Court judge, who is assisted by Andrew O’Connor QC and Martin Smith.

Left to right: Lord Anthony Hughes; Andrew O’Connor QC; Martin Smith. For details of the involvement of O’Connor and Smith in the prosecution of other British allegations of Russian poison attacks in the UK, click to read and this.

“Sir”, O’Connor told Hughes, according to the March 25 transcript, “the solicitor to the inquiry [Smith] has received, as you [Hughes] know, a letter from legal representatives [Chapman] of Sergei and Yulia Skripal, representing their designation as core participants in the inquiry…since the terms of reference for this inquiry expressly require you [Hughes] to investigate the events surrounding their poisoning, we submit that their significant interest in the matters to which the inquiry relates is self evident and, accordingly, we support the application that they have made. Sir, we have set out at paragraph 14 of our written submissions a list of those who in our submission should be designated as core participants and it may assist if I simply read that out…” O’Connor ended his list of names: “and finally, as I have said, Sergei and Yulia Skripal.”

O’Connor was testifying to hearsay at third hand. He and Hughes had been told by Smith, who had been told by letter from Chapman, who claimed he had been instructed by the Skripals to represent them and to apply to Hughes for authorization to participate in the open and closed parts of the inquiry. Hughes didn’t mention the Skripals by name during the March 25 hearing. He did announce: “I am currently minded to designate as core participants all those who are listed in paragraph 14 of Mr O’Connor’s written submissions.”

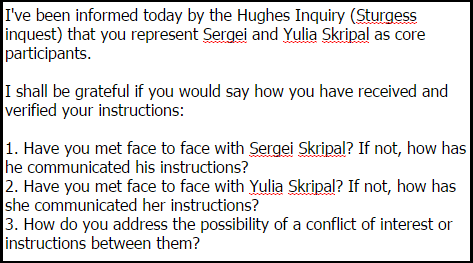

A few days later, Chapman was telephoned and then emailed at his London law firm, Kingsley Napley. He refused to answer. That was reported on April 6.

Chapman’s silence, his refusal to say he had communicated directly with the Skripals to verify they are alive, capable of giving him instructions, and not in prison or otherwise under duress, is the third of the Skripal secrets the government has allowed to slip out. By naming Chapman the British government and the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6), which was responsible for Sergei Skripal since he had arrived in England, had made Chapman the first and only source of public evidence of their fate.

The British press have not investigated this for more than four years. The Wiltshire county coroner David Ridley and the Cabinet Office coroner Dame Heather Hallett, who have been under the statutory duty to investigate the Novichok allegations since Dawn Sturgess died on July 8, 2018, did not report any contact with the Skripals. Since the Hughes Inquiry began, Smith claims he has relied on what Chapman told him by letter.

On April 8, Hughes and Smith were asked: “how do you know the [representation] appointment was made directly by the Skripals and how has Lord Hughes verified the personal wish of Sergei Skripal and the personal wish of Yulia Skripal?” Smith answered: “The Skripals’ application was received by the Inquiry from Kingsley Napley, whose conduct is regulated by the Solicitors Regulatory Authority (SRA). Solicitors such as Kingsley Napley have obligations to verify the identity of their clients (para 8.1 SRA Code of Conduct) and not to mislead the court or others (para 1.4 of the SRA Code of Conduct). Where a core participant or other person has appointed a qualified lawyer to act for them, the Chair is required by rule 6 of the Inquiry Rules 2006 to designate that lawyer as their recognised legal representative. The Inquiry has relied on an application submitted by regulated legal professionals in doing so. There is nothing unusual about this approach.” Hughes and Smith had evaded the questions asked; they were also evasive on the requirements of the Inquiry Rules No. 7 and the solicitors’ Code of Conduct Para 6.2; for the details, click. This was the fourth of the Skripal secrets the government has revealed.

Hughes had scheduled a second open hearing, to be followed by a closed one, on July 15. As the date approached, Chapman was asked “if you will confirm your participation in the Hughes Inquiry hearing scheduled for this coming Friday?” He refused.

His superior at the law firm, Sophie Kemp, who also heads the firm’s human rights group, was asked by email to answer the Skripal questions Chapman was stonewalling, and to clarify whether the law firm was being paid by the Hughes Inquiry to keep their representation of the Skripals secret and the Skripals silent. Kemp did not acknowledge the email or reply.

Taking money for such a gag in a public inquiry is the fifth of the Skripal secrets.

The sixth secret tumbled into the open when the video equipment broadcasting the hearing of July 15 failed to work. According to Nigel Coulson, a court technician, “the Cloud Video Platform equipment was tested beforehand and all was thought to be well. However there have been ongoing issues with equipment today.” The Cloud Video Platform (CVP) is the system the British courts use for remote proceedings; the court administration describes CVP as “an internet-based video meeting service and works like Zoom.” A national survey of judges and magistrates in January 2021 reported that CVP was more reliable than Skype but more popular than Zoom. Months later, the courts administration announced it was improving the remote-hearing technology with “a new Video Hearings Service (VHS), upgrading the Cloud Video Platform (CVP)”.

The CVP technology is not, however, the system the British courts depend on for the official, legal record of their hearings. This in-court system has been in operation for more than a decade now; it is known as Digital Audio Recording Transcription and Storage (DARTS). With DARTS in operation, “there is no longer a requirement for HMCTS [Her Majesty’s Court & Tribunal Service] to continue to use loggers and stenographers.”

The replacement of stenographers by DARTS was first reported here in April 2011. By 2020, the system was reported to be running on obsolete and unsupported Microsoft software vulnerable to cyber attack. The operating details of the DARTS system are a British government secret, as a Freedom of Information Act request for the DARTS manual revealed in September 2021.

“Apologies for the poor sound quality yesterday,” Hughes’ spokesman, Bernadette Caffarey, claimed by email. “I’m afraid the stenographer was listening remotely and this has resulted in a delay with the transcript.” The circumstances were reported in detail here. Like the court clerk, the spokesman omitted to mention DARTS.

To contrast Chapman’s and Kemp’s refusal to acknowledge the Skripals’ part in the Hughes Inquiry and their attempt to conceal Chapman’s presence in the courtroom on July 15, an enlarged partial screenshot of Chapman in the courtroom was published. This triggered an appeal to Hughes. According to Caffarey, the Dances with Bears publication “has been brought to the Inquiry’s attention as it contains a screenshot which was taken from the cloud video platform. As you correctly state in your blog ‘Court rules do not allow press camera or audio recording during the proceeding’. The Chair of the Inquiry [Hughes] did not give his permission for anyone to take recordings, videos or still shots of the proceedings…We would therefore be grateful if you would remove the two images of Mr Chapman from your blog with immediate effect.”

Did the judge confirm Chapman was present at the hearing? he was asked. Caffarey replied: “Mr Chapman did attend the public preliminary hearing last Friday and this will be reflected in the transcript.” The website images were then removed; the transcript has not followed. The Inquiry had interpreted the rules to apply to publication of Chapman’s presence at the hearing while the Inquiry continued in breach of the requirements to publish the transcript and the lawyers’ submissions.

The seventh secret was revealed on Friday, July 22, a full week after Hughes closed his hearing. This is the most sensitive secret of them all.

Despite repeated promises by the judge’s spokesman to publish the papers prepared by the lawyers before the hearing began and cleared for release by the security services, they have not been posted. Also, the transcript of what was said is still missing. This is despite the judge’s promise to have published it “as soon as possible”; and notwithstanding the availability of the back-up recording by DARTS. Revealed, this seventh secret is that the public hearing into the Novichok allegations is a now secret proceeding after the Sturgess family announced it suspects the government of lying.

Following publication, Martin Smith responded for the Inquiry: “The Inquiry is not part of the court service, and arranged for its own transcript to be taken at the hearing. That transcriber was attending remotely, and because of the technological problems was unable to take a full transcript. Because of those difficulties, the Inquiry is obtaining a transcript from the automated court recording system run by the court service to which [the publication] refers. This is not a real time service and it is taking a few days to prepare the transcript. It will be published in full as soon as possible. There is nothing secret about the hearing, which took place in public at the Royal Courts of Justice. The transcript is being prepared and will be published together with legal submissions shortly.”

Thirty-six minutes after this was received by email, the Inquiry published the transcript of the July 15 hearing. Click to read here. It records that Michael Mansfield QC, counsel for the Sturgess family, said in an exchange with Lord Hughes: “May I just put as a footnote, in 2018, although not disclosed, they [government] must have been prepared for disclosure. And why? Because two men were charged. Now, I appreciate the difficulties of bringing a case but, of course, by now there were three people charged. So those prosecuting must have considered, unless there it is an empty barrel, they must be considering the possibility they might have to go public with---- LORD HUGHES: With at least some of it. MR MANSFIELD: Yes, with at least some of it.”

Also recorded: Georgina Wolfe, counsel for the Home Department “and in a representative capacity for other government departments and agencies”: “In para.12 of our response note, which is at tab 10 of the bundle, we have also given examples of Russian espionage and interference against similar proceedings, available in open source, such as the Danish governing’s MH17 investigation and the World Anti-Doping Agency’s Russian doping investigation. In our submission, this shows that there is a very real risk of harm to the relevant staff and others and a risk of damage to national security if the relevant names are disclosed. That risk is substantial and immediate.”

The following exchange took place between Lord Hughes and Adam Chapman, identified as having “appeared on behalf of Sergei Skripal and Yulia Skripal”: “MR BERRY: Sir, I have nothing to add. LORD HUGHES: You have nothing. Right, thank you very much. MR BERRY: Unless I can assist you? LORD HUGHES: Thank you. Ms Clement, do you want to say anything? MS CLEMENT: Sir, the same for me.LORD HUGHES: And, Mr Chapman, do you want to say anything? MR CHAPMAN: The same for me. LORD HUGHES: Right.”

Leave a Reply