By John Helmer, Moscow

Sovcomflot (SCF), the Russian state shipping company, has been obliged by its accountants Ernst & Young to declare $75.5 million in costs and expenses from court orders by British judges over a series of lawsuits initiated by Sovcomflot’s chief executive, Sergei Frank (lead image, left) thirteen years ago. The money must be paid to Yury Nikitin, a former chartering partner of Sovcomflot.

The figure was released last week in Sovcomflot’s financial report for 2017. It does not include between $30 million and $50 million, which London sources estimate to have been Sovcomflot’s legal expenses and costs of compensating two other victims of Frank’s London litigation — Dmitry Skarga, Sovcomflot’s chief executive before Frank’s takeover in 2004; and Tagir Izmaylov (Izmailov), chief executive of Novorossiysk Shipping Company (Novoship) before Frank forced a merger between Sovcomflot and Novoship. The charges,compensation and penalties which Sovcomflot has been ordered to pay stem from the rulings by High Court, Court of Appeal, and Supreme Court judges that Frank was dishonest and vindictive in his claims against Nikitin, Skarga and Izmaylov.

Maritime analyst for Uralsib Bank in Moscow, Denis Vorchik, reported to clients this week the new financial accounting for the London litigation was the main reason for Sovcomflot to report a loss of $113 million for 2017.

Frank’s lockjaw has prevented recognition in the state company’s accounts of the financial costs of the London litigation since the first judgements were issued by High Court Justice Andrew Smith in December 2010 and March 2011.

“There is no support for the evidence of Mr. Frank,” Smith ruled, “whom, for reasons that I shall explain, I do not regard as a reliable witness. The claims against Skarga, he concluded, “are to be dismissed…The claims against Mr. Izmaylov are to be dismissed. [And] the claims against the other defendants are to be dismissed in so far as they are based upon these schemes.”

The judge believed Frank had chosen the British courts because he thought he had a better chance of winning his claims under British than Russian law. Had Sovcomflot taken its allegations and claims to a Russian court under Russian law, there would have been “formidable, and in my judgement insuperable difficulties”, Smith wrote. In addition “the defendants [Skarga, Izmaylov, Nikitin] would be protected by different limitation periods, which appear generally to be more favourable to them [in Russia] than those available under English law.” For the Sovcomplot archive, click to read.

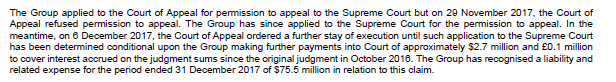

Smith’s rulings have been appealed by Frank to the higher UK courts for eight succeeding years. With each appeal, the accountants were instructed not to recognize the court-ordered costs and penalties in the financial reports and accounts because, as Sovcomflot and Ernst & Young claimed in 2016, “management is of the opinion that the defendants will more likely than not fail in their claim…. The Group will defend its position vigorously. Accordingly, no provision has been made.” The more vigorously Frank argued in court, the more frequently he was dismissed, and the higher the costs mounted. Postponement of the true bill for Frank’s litigation can be followed in the accountants’ note on contingencies and liabilities in the annual financial reports reproduced here.

Sovcomflot’s website does not publish full financial reports before 2010. Summaries from 2001 reveal that in 2004, Skarga’s last year at the helm, profit was $204.9 million. Since then Sovcomflot’s profits were below the Skarga mark, with peaks above $400 million in 2007-2008, and at $352.5 million in 2015. Frank reported a loss of $39.2 million in 2013, and in 2017 he reported the biggest loss in the company’s history, $113 million.

The last Kremlin meeting between Frank and President Vladimir Putin was on August 6, 2013. The Kremlin record does not report that their discussion touched on the reason for the company’s losses that year.

The 2015 profit, Frank explained in a press release, was “due to Sovcomflot’s ability to consistently execute its core strategy aimed at continued growth of our project business. Also contributing to our success were a solid technical performance and flexible chartering policy which helped Sovcomflot to take full advantage of the major rebound in the tanker markets.” Frank also congratulated himself. “The major source of our success is our human capital. I would like to commend the entire Sovcomflot team, both at sea and ashore, for their contribution to this achievement.”

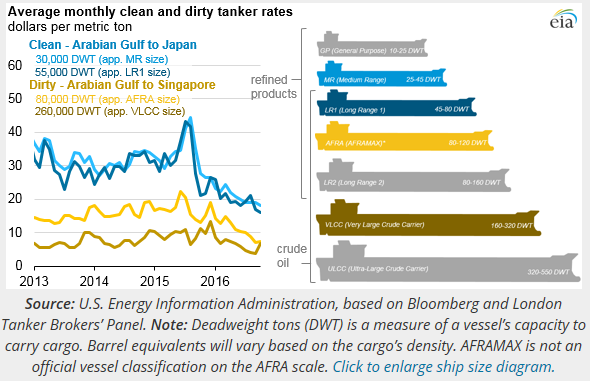

In the loss-making years Frank blamed the market. Sovcomflot’s 2013 loss, Frank claimed, was caused by “the financial crisis within the global tanker industry, which continued due to the discrepancy between supply and demand.”

Last year’s unprecedented loss Frank blamed on “the very strong headwinds seen in the conventional tanker markets over 2017, with freight rates down by almost 50 per cent reflecting one of the worst years in a quarter of a century…” Frank endorsed himself for “the robust nature of the Group’s business model has shown our ability to weather the low point of the shipping cycle”.

Sovcomflot’s latest press release, issued on Monday of this week, is headlined “SCF business model demonstrates its resilience in an extremely challenging year for tanker markets”.

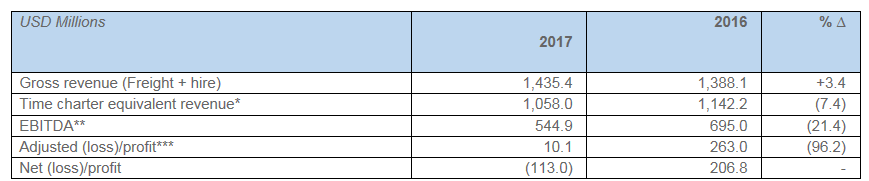

SOVCOMFLOT’S SUMMARY RESULTS FOR 2017

CLICK ON IMAGE TO ENLARGE

Source: http://sovcomflot.ru/en/press_office/press_releases/item95271.html

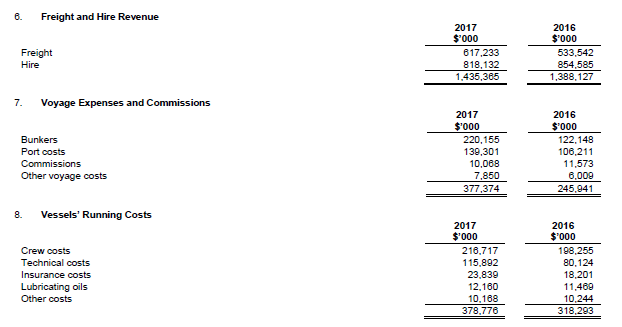

The company fails to explain how a modest 7.4% decline in time charter equivalent (TCE) revenue led to a 21% downturn in earnings (Ebitda) and produced the company’s dramatic transformation of its bottom-line from a $206.8 million profit in 2016 to a $113 million loss. TCE represents shipping revenues less voyage expenses; it is commonly used in the shipping industry to measure financial performance and to compare revenue generated from a voyage or spot charter to revenue generated from a longer-term time charter. Read the full financial report for 2017 here.

The Ernst & Young notes in the financial report indicate that operating revenues and costs were more or less stable between 2016 and 2017. This reveals no evidence that the cyclical downturn in tanker rates was the cause of Frank’s loss-making. With charter rates for his tankers locked in and protected against the volatility of spot rates, his revenues rose. But his management of voyage, vessel and crew costs failed to compensate.

When Frank began his campaign against Skarga, he accused him of failing to take advantage of spot tanker rates by committing too much of the Sovcomflot fleet to time charter. Frank followed with the allegations of corruption which the British courts have dismissed.

Maritime analysts who have followed the London court saga interpret Frank’s strategy as a high-risk gamble on expanding the Sovcomflot fleet, first by taking over Novoship, then by borrowing to build new vessels, in order to inflate the value of the company at privatization. Frank and Shuvalov hoped to earn a bonus on the capital gain, while Gennady Timchenko, the oil transportation oligarch, was the front-runner to acquire shareholding control from the state, and then multiply his profit from selling his shares to the market. Evidence of their scheming was presented in more than two months of trial in the High Court. Skarga and Izmaylov were removed from office, and then accused, according to the courtroom testimony, because they opposed Frank’s scheming, and for a time were able to convince government ministers. Prosecuting them on criminal charges in Moscow and pursuing a civil corruption case in London, according to the court record, were Frank’s tactics for discrediting their case against his Sovcomflot plan.

Left: Dmitry Skarga; right, Tagir Izmaylov. For the story of the High Court and Court of Appeal’s judgements balancing Frank’s dishonesty against the dishonesty of Yury Nikitin, read this.

“The Frank-Timchenko family clan is one of the most powerful in Russian business,” Russian maritime analysts acknowledge. They are also referring to the marriage between Frank’s son Gleb and Timchenko’s daughter Ksenia; for more details, read this. The US Government has listed Timchenko for sanctions, but the latest US Treasury list of Russian state company chiefs and oligarchs omitted Frank. Read that story here.

According to one Russian industry source, Frank “has done his job well. He provided the transportation of Russian hydrocarbons to foreign buyers. If he hadn’t, the SCF loss could have been bigger.”

Maritime industry sources concede that leveraging the existing fleet to borrow for fresh vessels in the uncertain oil price and tanker rate conditions since 2008 was a risk. Borrowing by Frank for new vessels also contributed to the financial failure last year. The cost of interest payments doubled from $54.7 million in 2016 to $103.8 million in 2017. Frank was not only borrowing heavily, he was doing so at rising interest rates for loans of less than a year at a time.

CLICK ON IMAGE TO ENLARGE

As the table indicates, Sovcomflot’s borrowing has grown by 42% over the past two years. Frank has now run up Sovcomflot’s debt to its second highest level in the company’s history; peak debt was $2.36 billion in 2012.

But despite the judgements against Frank and Sovcomflot since 2010, Frank has tried to postpone making the court-ordered payments through repeated applications to the Court of Appeal and Supreme Court. This is how the latest financial report describes the ongoing appeals. The last sentence is the first recognition of the accounting cost of Frank’s loss to Nikitin:

Denis Vorchik, the maritime industry analyst at Uralsib Bank in in Moscow, reported this week the unprecedented Sovcomflot loss “is caused in particular by the [$75.5 million] expenses connected with the judicial proceedings of the company in the courts of Great Britain concerning transactions made during the period from 2000 to 2004.”

His conclusion is that Sovcomflot under Frank cannot be privatized in 2018, despite repeated pledges by the government of its intention to sell shares. “Placement of shares in 2018 is improbable,” Vorchik concluded in his report. “The debt burden of Sovcomflot remains high with a net debt to Ebitda [earnings] ratio of 6x. Discussion of privatization of Sovcomflot by the state has been going on since 2012, but every year the placement of shares has been postponed. This time, besides the deterioration in [the company’s] financial performance and the high debt burden, placement of shares of a state company at international stock exchanges is also not encouraged by the political situation.”

Leave a Reply