By John Helmer, Moscow

@bears_with

The paintings of Thomas Gainsborough, the most famous English portraitist of the 18th century, have almost nothing to do with Russia at war today.

Almost, but not quite nothing.

Gainsborough painted no Russians, and only one of his paintings, “Woman in Blue” can be found in Russia today. It’s an inferior work from 1770 in which Gainsborough made a mess of his sitter’s mouth; or else she had syphilis and Gainsborough was painting her in too much of a hurry to cover it up properly.

Eight years later Gainsborough set the British record (still unbroken) of the fastest masterpiece ever composed – 48 minutes flat for his portrait of Samuel Linley. He also set the record for the most expensive commissioning fee at the time – one hundred guineas a portrait, or about £20,000 today. In 1922, his “Blue Boy” (lead image) set the record for the sale at auction of a British painter and of a painting sold anywhere — £728,000 (£42.4 million today).

Left: “Woman in Blue”, painted in Bath in 1770; source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Woman_in_Blue Right: Samuel Linley, painted in London in 1778; Linley was 18 years old at the time and died a few weeks later.

The reason for Gainsborough’s success at making money in his lifetime, as well as his fame ever since, is that he invented a new truth in painting a likeness, in reproducing the truth of character in a portrait. Sprezzatura, an earlier Italian courtier’s term, was Gainsborough’s style of painting – it meant studied carelessness. He not only painted at top speed; he made that speed visible on the canvas as if it had been dashed off and was unfinished. But what looks unfinished in Gainsborough’s pictures was intended, so that the likeness appears to be even more truthful. Dramatically so, like a caricature, a cartoon, or a comic.

In a new book on Gainsborough by Susan Sloman, there’s a point at which she almost admits this. A portrait Gainsborough did in 1774 of Lord Hastings in military uniform makes him — judges Sloman — “appear lanky to the point of caricature.” American and Hindu independence fighters of the time thought that’s the least he deserved; Sloman doesn’t dare say the word again. Click to open the book.

Left, Susan Sloman, Gainsborough in London.

Right: Gainsborough’s 1784 portrait of Francis Rawdon, later Marquess of Hastings – the British Army soldier who executed American general Joseph Warren at the Battle of Bunker Hill (1775) and went on to defeat the Hindu Peshwa forces in the last of the Maratha wars 1817-18.

Gainsborough’s execution of the style was new in England.

But the likenesses he produced – at a rate of more than 400 between 1774 and 1788; that’s an average of 2½ every month – were hardly truthful. His subjects’ hands were all the same – elegantly long fingers identical between men and women, whatever their age. His subjects’ shoulders were almost always sloped. Their skin was always whiter than Clorox or White King; at the time Gainsborough’s female subjects were keen to conceal the tanning effects of the sun. His men – soldiers, huntsmen, farmers – also managed to stay whiter than can have been possible in their line of work. Noses were also standard fixtures on the canvases to a degree that is impossible on Pall Mall, St James’s Street, Jermyn Street, or St James’s Square today; not less so in the 1780s. Ears, feet, shoes, and boots – all the same.

And yet the likenesses ring true – that is Gainsborough’s fame. It was the London art market’s judgement at the time, as the affordability of art works for decorating walls moved down market from royal palaces and aristocratic mansions into bourgeois housing, from the single canvas to the multiplication of aquatints and etchings. Gainsborough’s story is also the story of this takeoff of art as a commodity starting from the establishment of the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 1768.

Russian portrait painters didn’t begin to come into their own until almost a century after Gainsborough; that was because the Imperial Academy of Arts which started in St. Petersburg in 1757 – a decade ahead of London – was a foreign monopoly exploited by Germans, French and the occasional Scotsman. Read that story here. Just how industrial and lucrative the portrait business was in Russia can be seen in the career of Vladimir Borovik (aka Borovikovsky), who was a favourite of Catherine the Great, and who turned out about 400 portraits between 1780 and 1825.

Gainsborough’s paintings of peasants, especially peasant girls half-undressed, were bestsellers at the time in London, not quite so popular in St. Petersburg. They were not recognized as the cartoons they were until Russian realism took off for peasant girls a century later.

Left: Gainsborough’s “A Peasant Girl Gathering Faggots in a Wood” of 1782. Right: Ilya Repin’s “A Peasant Girl” of 1880. Sloman acknowledges the 18th century soft-core sex appeal “that is…disquieting to twenty-first century eyes”. She also reveals that Gainsborough’s popular cottage-door pictures, with compositions of good-looking and large breasted women surrounded by babies and toddlers, was connected to the London Foundling Hospital in what was considered a charity at the time; baby farming today.

Looking back at Gainsborough in London from Moscow today, retrospect gives the viewer an ideological reminder of what was a true likeness then and now – not only what has changed in the mind’s eye, but the political reason for it. Actually, what Gainsborough achieved was something Sloman’s book provides the evidence for, but doesn’t recognize herself. And here’s the lesson for Russia.

Gainsborough was the first painter to devise a form of portrait whose veracity in likeness was a combination of caricature (to the advantage of the sitter); of political propaganda (for kings, aristocrats, and money men); and of commercial advertising. Gainsborough was the first great artist to produce fashion plates which converted his pictures of the royals at St. James’s Palace, down the street from his house on Pall Mall, into the lucrative businesses of that quarter of London, many of them still there – shoemakers, tailors, hatters, hairdressers, cosmetic sellers, gunmakers, antiquaries, picture galleries, and art auction houses like Christie’s.

This is the stuff on which fortunes are spent, state fortunes as much as private ones.

Left to right, Gainsborough’s portraits of King George (1781); Queen Charlotte (1781); three of the king’s daughters, “The Three Princesses” (1783-84). Gainsborough never painted those who were at war with Britain at the time. He borrowed from French painters and anticipated their impressionism which came after him. But he was commercially jealous and competitive, dismissing the French painting of his time as “gingerbread”.

Compare these likenesses of the faces which represented the power of the British state in Gainsborough’s time to the face of state power which Russians have represented to themselves more recently — and of one face which the British insist is a true likeness of Russian state power today.

Boris Vladimirsky, “Roses for Stalin”, 1949.

Vladimir Putin in British newspapers since 2014 -- The Scotsman; The Guardian; and The Times.

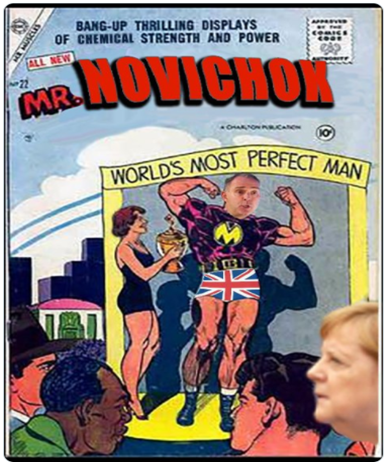

The amount of money spent by the British and US governments, and the NATO alliance, on portraying this cartoon of Vladimir Putin (lead image) as the true likeness of Russia is enormous. It’s the equivalent of the royal propaganda which Gainsborough was commissioned to produce two centuries ago. To be sure, Gainsborough’s pictures were intended to instill tender sentiment, even love for the subject. The current pictures are designed to instill hatred for the subject and readiness to go to war. Naturally, the picture-making and selling is a lucrative business for the individuals who have passed through this website as cartoons themselves – Theresa May, Boris Johnson, Mark Sedwill of the Cabinet Office, Alexander Younger of MI6, et al.

Centre, Sir Mark Sedwill, national security advisor and Cabinet Secretary to Prime Minister Theresa May, fabricator of the first Novichok operation against Russia, the Skripal affair; right, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, promoter of the second Novichok operation, the Navalny affair. For more Gainsborough quality at discount to the market price, click to read THE COMPLETE DANCES WITH BEARS COMIC BOOK.

That President Putin is unceratin of the strength and weakness of his own propaganda organisation — the most expensive in Soviet or Russian history — in combating the Anglo-American foe he indicated himself at the Valdai Club last week. This is an information warfare platform paid for by the Russian government and closely supervised by the Kremlin.

“There is no fence against ill fortune, Margarita”, Putin told Margarita Simonyan, head of Russia Today (RT), the leading state media organ. “First, regarding the retaliatory measures, I think we need to be cautious when someone makes mistakes like this [foreign agent sanctions for journalists], and I do believe that you have suffered from them, when a channel is closed or you are unable to work. I know about the fact that your accounts were blocked and that you could not open, etc. There is a plethora of instruments to this effect… On the one hand, of course, they are infringing on freedom of speech and so forth, which is a bad thing. But since they are doing this, you and I have to think about how to spread the word about the fact that they are cancelling you, and then more people will become interested in what you do.”

Leave a Reply