By John Helmer, Moscow

United Company Rusal, Russia’s aluminium monopoly, lost a prop for its sale revenues, debt repayments, and share price this week, when the UK Court of Appeal allowed a new aluminium stocking rule by the London Metal Exchange (LME) which Rusal has been opposing since July 2013.

The LME aims to end over-stocking of aluminium in warehouses, and cut the premium Rusal charges for customer deliveries on top of the LME contract price for the metal. That rising premium has been worth 20% of the aluminium spot price, according to the latest Rusal figures to June 30. This amounted to $319 million of Rusal’s aluminium sales revenues in the second quarter of the year. Cut the premium in half, or remove it altogether, as aluminium market regulators in London, Hong Kong, and Washington have been trying to achieve, and Rusal would be producing aluminium at a loss; its second-quarter profit of $129 million — its first positive bottom-line in two and a half years — would be wiped out.

A three-judge panel of the Court of Appeal ruled on October 8 to overturn a High Court judgement in Rusal’s favour, issued six months ago on March 27. The new judgement was written by Justice Dame Mary Arden (right); concurring were Justice Sir Richard McCombe and Justice Dame Elizabeth Gloster, defender of Roman Abramovich in his 2012 High Court victory over Boris Berezovsky.The full text of the new ruling can be read here.

A three-judge panel of the Court of Appeal ruled on October 8 to overturn a High Court judgement in Rusal’s favour, issued six months ago on March 27. The new judgement was written by Justice Dame Mary Arden (right); concurring were Justice Sir Richard McCombe and Justice Dame Elizabeth Gloster, defender of Roman Abramovich in his 2012 High Court victory over Boris Berezovsky.The full text of the new ruling can be read here.

Arden said the speed of the new judgement was warranted because Rusal had been making money out of the court delay. “Where judicial review is sought in a commercial setting of this kind,” Arden wrote, “parties may make or lose money as a result of the delay caused by a legal challenge and the regulation of the market may be undermined. Accordingly, the court has to act with considerable care lest the integrity of the market is prejudiced by an unsustainable legal challenge.”

In March High Court Justice Stephen Phillips had decided that introduction of an LME rule to accelerate movement of aluminium in and out of the warehousing system had been unfair to Rusal. The text of his judgement can be read here.

In March High Court Justice Stephen Phillips had decided that introduction of an LME rule to accelerate movement of aluminium in and out of the warehousing system had been unfair to Rusal. The text of his judgement can be read here.

Phillips has been condemned in unusually explicit language by the Court of Appeal. He had “misinterpreted” and “misunderstood” the prevailing case law. He had made errors of interpretation regarding the LME’s investigations of the warehouse problem before it promulgated the new rule. He had also made mistakes of fact, failing to take account of the information available to the LME, including common market knowledge. “The court,” according to Arden, “cannot ignore information which was well known to the consultees even if it was not set out or referred to in the consultation document. Any other conclusion would lead to cumbrous and potentially self-defeating consultation exercises where the real issue is obscured by common knowledge.”

Bottom-line — the new LME’s warehouse rule to speed up aluminium shipments, and cut costs, is not unfair; the procedure by which the LME had arrived at the rule last year wasn’t unfair either. Arden versus Rusal, again: “The LME cannot fetter the way it exercises its statutory duty by reference to what is in the commercial interests of some of the participants in the market.”

What Rusal had attempted to do was also wrong, the judge has ruled. “It is also clear that Rusal is not challenging the [LME rule] consultation process in order to make some response on the rent ban option which it has been unable to do for want of information but to pursue some other objection of its own. Even though Rusal has standing, its complaint is nonetheless unreal. It has no support from any consultee who feels that it was misled.”

“We are pleased to be moving ahead with our planned reforms following our success in the Court of Appeal,” the LME Chief Executive announced yesterday. “As the world’s leading base metals exchange, the LME has a duty to ensure the integrity of its reference prices and the operation of a fair and liquid market for all industry participants… While it is true that market conditions have also improved since 2013, the market knows that a proportion of global metals production today still flows into storage. Without the LILO rule, large amounts of metal could have been directed to affected warehouses, thus further lengthening queues. However, we believe that the anticipation of LILO has meant that this has not occurred on as large a scale as it would have done otherwise. And the introduction of LILO will ensure that, over time, stocks – and eventually queues – at the two remaining affected warehouses should fall.”

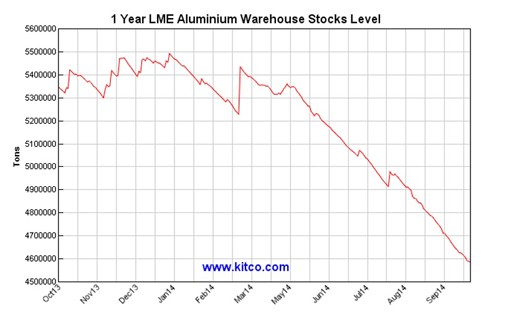

The LME publishes aluminium stocking data for the warehouses it covers in the global market. According to the latest evidence, stock levels have been falling since the start of the year.

Source: http://www.kitcometals.com

But these data do not reflect an accurate picture of aluminium stocking outside the LME’s means to monitor. Also, precisely how much aluminium Rusal produces, sells, and with Glencore, a shareholder and prime trader, keeps in unsold stockpiles, is also unmeasured by the LME, and unreported by either Rusal or Glencore. The story of Rusal’s hidden aluminium can be followed here.

The attempt to make the aluminium market more transparent, and stop price-rigging by producers and traders, as well as the international banks controlling the warehouses, can be read here.

Last year’s US media campaign to expose the aluminium warehouse premium, and reform the warehouse stocking and pricing rules, didn’t mention Rusal or Glencore. Sponsored by American drinks companies, whose beverage cans are made of aluminium, the lobbying targeted Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan. When Reuters attempted to probe and publish the role of Rusal and Glencore, it received a defamation lawsuit threat from a London law firm.

What was called the aluminium warehouse scam in Washington is treated gingerly by Justice Arden. “There is a free market in base metals as well as a market in the LME,” she has written, but there is also market-rigging. “The LME price is used to help ‘discover’ the free market price. The LME price is always at a discount to the free market price because of (a) the need to pay warehouse charges (so that the metal is, in the jargon of the market, ‘free on truck’) and (b) the inconvenience of having to obtain delivery from the warehouse. But, as queues have lengthened (thus creating an element of uncertainty in the warehouse rent to be paid by the holder of an LME warrant seeking to obtain physical delivery of the metal to which the warrant relates), it has become increasingly difficult to discover the free market price. There is a divergence of view between, on the one hand, producers and warehouse operators with warehouses where there are queues, who benefit from the queues, and, on the other hand, consumers who might have to pay higher prices and warehouse operators with warehouses without queues who face competition because producers prefer warehouses with long queues.”

The Court of Appeal explicitly recognizes that as market demand for aluminium has been falling, Rusal’s interest is in keeping the uncertainty of supply up. So the rise of the warehouse premium has helped offset the decline of Rusal’s revenues from sales at the purported market price. The effective price for Rusal was the LME spot price plus the premium. The proposed LILO rule, to which Rusal objected, requires that the amount of new metal which a warehouse, having a queue of more than 100 days, could accept (‘load in’), would be restricted and tied to the amount which it had delivered (‘loaded out’) – hence LILO.

By cutting the volume of accumulating stocks and the queue for deliveries, the rule aims to cut the premium, and thereby cut the price of the metal. “It is inevitable,” Arden said, “that Rusal should be concerned with the potential losses to producers that might result from implementation of the LILO option. It was possible that implementation would lead to an increase of metal on the free market and to a fall in the price which would be contrary to the interests of producers.”

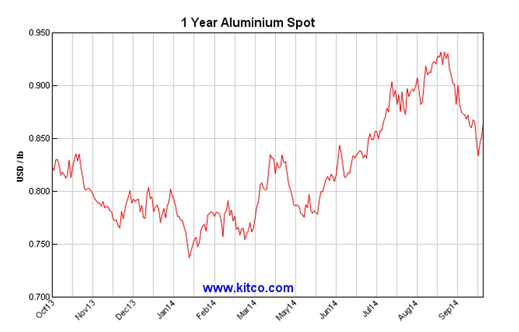

The Arden ruling will not be appealed, Rusal has announced; the LME says it expects to start the new rule on February 1, 2015. In the first day’s trading after the court ruling was announced, Rusal’s share price dropped 1.9% to HK$4.08 (53 US cents). Its market capitalization is now the equivalent of US$8 billion. Rusal’s share price had started falling from September 12, just as the spot price for aluminium started downwards; well before the market could guess what the Court of Appeal would rule, or when. Rusal’s year-to-date peak has been HK$4.76. It’s now down by 13%. The price of aluminium has fallen 9% over the same interval.

SHARE PRICE TRAJECTORY FOR RUSAL, YEAR TO DATE

Source: http://www.bloomberg.com

Rusal responded with a release saying it is “disappointed by today’s result. However, it notes that, as a result of changed conditions in the aluminium market, the LME’s rule change, if now adopted, is likely to have little effect on queues or premiums. This is because, as a consequence of recent production cuts, the market is no longer in surplus but rather is in deficit. Accordingly, market conditions today are fundamentally different than the conditions in existence at the time the rule change was first proposed.”

Source: http://www.kitcometals.com

This morning the spot price is US$1,885.50, and falling. The 3-month future spot price is $1,916, and also falling. The market is showing no confidence that conditions for aluminium pricing are as “fundamentally different” as Rusal has declared.

Rusal’s chief executive and control shareholder, Oleg Deripaska (lead image) claimed yesterday that Rusal’s objective in going to court in London had been “to release more data to the market so as to allow participants to make a proper assessment of its adequacy and impact. The LME declined to do so, either at that time or in the intervening period between the decision of Mr. Justice Phillips and today’s Court of Appeal judgment. Accordingly, that judgment will do little to address the problems caused by disparities between the LME price and premiums or the general lack of transparency.”

Rusal production and sales reports tell a different story. According to the first-quarter results, “[the] LME aluminium price continued its fall and reached the lowest record since the second quarter of 2009 of USD1,708 per tonne demonstrating a 3.4% decrease compared to USD1,769 per tonne in the last quarter of the prior year. This negative trend was compensated by historically maximum realized premiums over the LME aluminium price of USD336 per tonne in the first quarter of the current year, 21.3% higher than USD277 per tonne in the fourth quarter of 2013.”

The second-quarter and first-half results reveal, according to the Rusal report, that “revenue in the first half of 2014 decreased by 15.7% to USD4,384 million as compared to USD5,203 million in the first half of 2013 due to a 12.6% decrease in physical aluminium sales and continued pressure of the LME price down to an average of USD1,753 per tonne, a 8.7% decrease compared to the same period of 2013, partially offset by historically high premiums over LME aluminium price of USD347 per tonne for the first half of 2014. Revenue in the second quarter of 2014 increased by 6.5% to USD2,261 million as compared to USD2,123 million for the first quarter of 2014, following a 4.6% increase in aluminium sales volumes, a 5.3% increase in the average LME aluminium price and a 5.4% growth in the average realized premiums over the LME price.”

In short, according to Rusal’s reports, the warehouse premium was rising steadily even when, as Deripaska says, market demand was contracting, supplies to the market falling, and warehouse stocks dwindling. Rusal’s forecast for the months ahead, issued at the end of August, was that as the supply-demand balance tightened, the warehouse premium would continue to grow, even if the spot price of the metal did not. “In the second half of the year, we expect the LME spot aluminium price to remain around current levels and we see a potential upside for physical premiums.”

The judgement of the Court of Appeal upsets the upside.

Leave a Reply