By John Helmer, Moscow

@bears_with

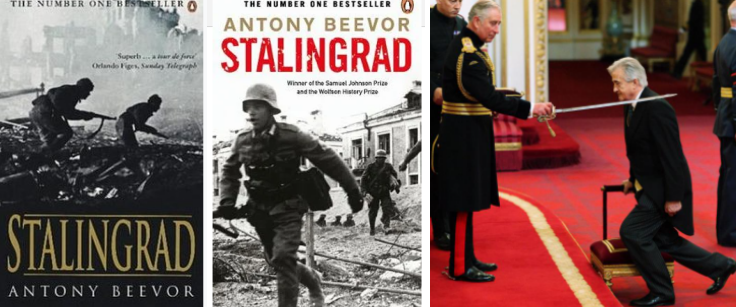

It was seventy-nine years ago, in the month of January 1943, that the Battle of Stalingrad ended in the defeat and capitulation of the German Sixth Army (lead image, left). It was, according to the British historian of the battle, Antony Beevor, “the most catastrophic defeat hitherto experienced in German history.” Militarily, it also started the defeat of Germany on all fronts, the end of the war, and the division of Germany and eastern Europe into Russian and American control zones.

The reversal of that outcome, and the steady expansion of the American control zone eastwards, across Germany, then across the Warsaw Pact and the Soviet zones, to the Russian frontier, continues today. Rewriting the story of the Battle of Stalingrad is the propaganda part of this military campaign.

I n 2017 Bevor was awarded a British knighthood as “Military Historian and Author. For services in support of Armed Forces Professional Development”. By that year Beevor’s 493-page history, Stalingrad, was into its third paperback edition, and its cover had been changed from a photograph of Russian troops advancing to a photograph of German troops advancing.

That year too, the British government was three years into the new US-led war against Russia in eastern Ukraine and on the Black and Baltic Seas.

Re-reading Beevor’s history of the Stalingrad battle this month, as Anglo-American state propaganda organs continue broadcasting that Russia is about to start a new war in Europe by invading Ukraine, is a fresh lesson of how relentless race hatred against Russians turns out to be. From this follows the second lesson of Beevor and his book: his sympathy for the German version of race hatred against Russians, pervasive in his history book, prepares readers for a new war against Russians for what Beevor repeats a German officer as calling “a war of two world outlooks” and another calls Russian insects: “Lice are like the Russians. You kill one, ten new ones appear in its place.”

In most countries of Europe (including Russia) race hatred is a crime. In Beevor’s case, it’s military history “in support of Armed Forces Professional Development”.

Left: the cover of the first paperback edition of Stalingrad, published by the Penguin group (including the US imprint Viking) on May 6, 1999. Centre: the cover of successive Penguin editions to 2017. Right: Beevor is knighted by Prince Charles, the heir apparent and Prince of Wales, on February 17, 2017. Follow Beevor’s awards on his website: https://www.antonybeevor.com/

Beevor admits in his preface of 2010 he was “lucky enough to be one of the first foreigners to be allowed” to read in the Podolsk archive of the Russian Ministry of Defence, including the daily reports from the Stalingrad front “on almost every night of the battle”. He also claims “there was no propaganda gloss of any sort… This was because Stalin was so concerned with the outcome of the battle he wanted the absolute truth.” Beevor’s access to the Russian military archive began when he started his research on the book in 1994 and lasted until the book appeared in 1998. His access coincided with the presidency of Boris Yeltsin. By 2001, Beevor admits, the “the half-open window is now almost completely closed”. Beevor doesn’t say he knows why. He reports instead “research in Germany was far more straightforward”. He does not report that the Bundesarchiv-Militararchiv at Freiburg-im-Breisgau was “the absolute truth”, but he implies it was even better, because he “found an unexpected wealth of material on morale and conditions, whether reports from doctors, usually acute observers of human suffering, or from German military chaplains.”

To read Beevor’s history — equally told, he claims, from the records of both sides — is also, as Beevor intended, the story of Stalingrad as the end of the German attempt to defeat and destroy the Soviet Union, and the beginning of the western allies’ attempt to do the same thing. He claims to tell the first; by repeated innuendo he hints at the second.

Last month, in his speech to the Russian officer corps on December 21, President Vladimir Putin asked explicitly for an answer to this second question. It’s now the central question of Russian strategy and security.

“Sometimes I wonder,” Putin said. “Why did they [the US and its NATO allies] do all this in the then conditions?” By then, Putin was referring to the period of Boris Yeltsin’s administration, when Beevor was at work in the Russian Defence Ministry. “This is unclear,” Putin answered himself. “I think the reason lies in the euphoria from the victory in the so-called Cold War or the so-called victory in the Cold War. This was due to their wrong assessment of the situation at that time, due to their unprofessional, wrong analysis of probable scenarios. There are simply no other reasons.”

Of course there are other reasons – and in the same speech Putin suggested them. “American specialists were permanently present at the nuclear arms facilities of the Russian Federation. They went to their office there every day, had desks and an American flag. Wasn’t this enough? What else is required? US advisors worked in the Russian Government, career CIA officers gave their advice. What else did they want?”

Two days later, at his annual session with Russian and foreign press, Putin repeated and amplified on the same remark to a reporter from the Murdoch media: “In 1991, we divided ourselves into 12, I believe, parts, and we did this ourselves. Still, it seems that this was not enough for our partners. They believe that Russia is too big as it is today. This is because the European countries themselves turned into small states. Instead of vast empires, they are now small states with 60 to 80 million people. However, even after the Soviet Union collapsed, and we were left with just 146 million, it is still too much for them. I believe that this is the only way to explain this unrelenting pressure.”

Left: President Putin responding to foreign press question on December 23, 2021. Centre: Petr Kozlov, a BBC Russian Service journalist -- Min. 0:45. Putin selected Kozlov by saying that Dmitry Peskov would not select the BBC but he would do so himself. Right: Diana Magnay, Sky News London -- Min 1:16.

“Take the 1990s, for example. The Soviet Union did everything to build normal relations with the West and the United States. I have said this many times, and I will repeat it, so that your listeners and viewers understand… We had representatives from American intelligence services at our nuclear, military facilities; monitoring Russia’s nuclear weapons sites was their job. They went there every day and even lived there. Many advisors, including CIA staffers, worked in the Russian Government.”

Putin also told a Russian reporter for the BBC: “speaking of history, as a reminder, our opponents have been saying throughout the centuries that Russia cannot be defeated, but can only be destroyed from within, which they successfully accomplished during World War I, or rather, after it ended, and then in the 1990s, when the Soviet Union was being dismantled from within. Who was doing it? Someone serving the interests of others that run counter to the interests of the Russian and other peoples of the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union, and the Russian Federation today.”

Too big, too powerful, too Russian for Europe or the US to control, even when they were occupying Russian military command centres — Putin is now saying the destruction of Russia has been the strategic objective from long before the German invasion of 1941 and the battle of Stalingrad that followed. It then became the strategic imperative of the Yeltsin period when “someone serving the interests of others” was in power; click for more on the strategic significance of Putin’s break with Yeltsin.

Between 1994 and 1998 Beevor was one of the foreign flag-flyers at the Defence Ministry, but “the absolute truth” of Stalingrad is not what he was after, nor is it the conclusion he intends a reader of his book to reach.

To understand Beevor’s meaning and intention, there are several key statistics to be drawn out of the computer search function and indexing of the e-book. The term “enemy”, for example, appears 164 times in Beevor’s tale. Sixty-eight times (41%) Beevor uses “enemy” to refer to the German invaders and attackers. By comparison, he uses “enemy” to refer to the Russian defenders 96 times (59%). On this not so subtle balance of who was the enemy then – and who still – Beevor takes the German side.

He then tips the balance more forcefully in his accounting for the German and Russian commands, starting at the top. Adolf Hitler, for example, is mentioned 330 times; Joseph Stalin, 212 – the victor of the battle appears one-third less than the loser. Field Marshal Friedrich Paulus (lead image, 1st left) , the capitulating head of the German Sixth Army at Stalingrad, appears 307 times; his Russian counterparts in command of the Stalingrad and Don Fronts and the 62nd Army – Colonel-General Andrei Yeremenko, 44; General Vasily Chuikov, 105; and Colonel-General (later Marshal) Konstantin Rokossovsky, 25. Adding General of the Army (later Marshal) at Stavka in Moscow, Georgy Zhukov, 77, produces a sum for the entire Russian command of just 251 mentions – 18% less than for Paulus by himself.

The lopsidedness of Beevor’s account of the fighting is just as obvious further down the command chain. In the air, for example, Colonel-General Wolfram Freiherr von Richtofen of the Luftwaffe is referred to 57 times. His counterparts in Russian military aviation included General Timofei Khryukin (mentioned once); Major-General (later Marshal) Sergei Rudenko (zero), and Major-General S.A. Krasofsky (zero).

On the ground, the German general commanding the Panzer tank corps, Hans Hube, was reported 44 times; his Russian counterpart, General Prokofy Romanenko, just 4. Directing infantry and artillery, the German general Walther von Seydlitz-Kurzbach, was cited 78 times compared to less than half as many for the three Guards generals, Aleksandr Rodimtsev (30), Viktor Zholudev (7) and Stepan Guriev (2).

With these German accounts of the battle vastly outnumbering the Russian in Beevor’s story, it’s unsurprising that his explanation for the German defeat and Russian victory is equally unbalanced.

Statistically, his explanation is that the Germans made mistakes but (with the exception of Hitler) they were morally superior to the Russians. One of the biggest of the German mistakes, according to Beevor, was Richthofen’s order to the Luftwaffe to bomb the city into rubble, from which it then proved more difficult than the Germans had anticipated to defeat the defenders. An even bigger mistake, “the biggest made by the German commanders” was “to have underestimated ‘Ivan’, the ordinary Red Army soldier. [The Germans] quickly found that surrounded or outnumbered Soviet soldiers went on fighting when their counterparts from western armies would have surrendered.”

Of the 19 mistakes Beevor identifies in his history of the battle, 15 (79%) were made by the Germans.

By contrast, according to Beevor, the Russians fought to the death for one racial reason, one moral. “Russian tolerance of suffering”, Beevor claims to have discovered – he provides no footnote for his source – “Marxist-Leninist doctrine had managed to exploit so successfully.” “Did the Red Army manage to hold on against all expectations through genuine bravery and self-sacrifice,” Beevor began his book with this innuendo camouflaged as a question, “or because of the NKVD and Komsomol blocking groups behind, and the ever-present threat of execution by the Special Departments?”

Beevor answers without the evidence of the survivors. “Interviews with veterans and eyewitnesses, especially whose conducted over fifty years after the event, can be notoriously unreliable.,.but when the material is used in conjunction with verifiable sources, they can be extremely illuminating.”

Left: Richthofen during the Battle of Stalingrad. Right, Chuikov, photograph taken in 1943-44.

Instead, Beevor deploys adjectives and adverbs. The qualifier “pitiless”, for example, appears 6 times; in every instance, Beevor applies it to Russians. The qualifier “ruthless” was used 11 times, seven for Russians, four for Germans. “Merciless” is applied three times – all to Germans. Chuikov draws Beevor’s adjectival bile several times over. First introduced by Beevor as “one of the most ruthless of this new generation [of Red Army officers]…. His strong peasant face and thick hair were typically Russian”. During the worst of the Stalingrad fighting, he had become “harsh and blunt”, as he “began to instil terror into any commander who even contemplated the idea of retreat”. Beevor provides no source or reference for these judgements; they are his own. He also attacks Chuikov’s “appalling wasteful policy of repeated counter-attacks [which] astonished German generals, although they were forced to acknowledge that it wore down their troops.” This too is Beevor’s conclusion for which he provides no reference in the captured German documents in the Russian archive, or in the archives in Germany, or in Beevor’s interviews.

Thus, Beevor’s personal animosity towards Bolsheviks, communists, the Russian revolution, Marx, Lenin, and Stalin are thoroughly intermingled now, as he also reports they were then with Winston Churchill and Joseph Goebbels. Hitler’s version of the combination, Beevor acknowledges, became the German Army command’s version, just as it was the German foot soldier’s version. “The idea of Rassenkamf, or ‘race war’”, reports Beevor, “gave the Russian campaign its unprecedented character”. That was then.

Now, adds Beevor, “many historians argue that Nazi propaganda had so effectively dehumanized the Soviet [sic] enemy in the eyes of the Wehrmacht that it was morally anaesthetized from the start of the invasion. Perhaps the greatest measure of successful indoctrination was the almost negligible opposition within the Wehrmacht to the mass execution of Jews, which was deliberately confused with the notion of rear-area security measures against partisans.” This is Beevor talking; he cites no source or reference.

He also proposes that between the Germans and Stalin there was moral equivalence. Stalin’s “lack of concern for the starving population was as callous as that of Hitler”. Read that judgement of Beevor’s at page 37 of the paperback edition, page 57 of the e-book version – no footnote, source, or reference. Beevor reserves “callous” for Stalin, and repeats the term a second time, again with equivalence to Hitler: “Stalin’s callous abandonment of General Andrei Vlasov’s 2nd Shock Army, cut off in marshes and forests a hundred miles north-west of Demyansk [in July 1942], did not serve as a warning to Hitler, even [sic] after the embittered Vlasov surrendered and, throwing in his lot with the Germans, volunteered to raise an anti-Stalinist Russian [sic] army.”

“Whatever one may think about Stalinism”, Beevor concludes for his readers, “there can be little doubt that its ideological preparation, through deliberately manipulated alternatives, provided ruthlessly [sic] effective arguments for total warfare.”

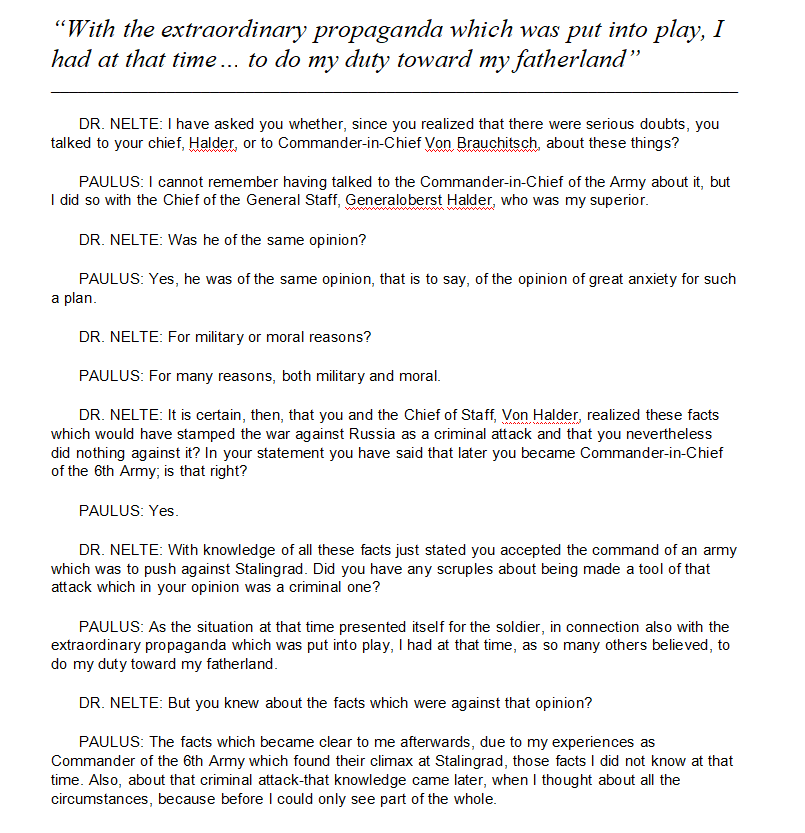

The book concludes with anecdotes about the two commanders in chief – Paulus and Chuikov. Beevor makes a passing reference to Paulus’s summons to testify as a witness in the Nuremberg war crimes trials of his superiors in Berlin, Wilhelm Keitel and Alfred Jodl, both of whom were convicted and hanged. Beevor says nothing about Paulus’s testimony about what had motivated the German invasion of the Soviet Union and his role in the decision-making. This is how Paulus answered:

Source: https://avalon.law.yale.

Beevor displays personal sympathy for Paulus who “aged rapidly and his tic was worse than ever. In 1947 his wife died in Baden-Baden, without seeing her husband again. One can only speculate as to her feelings about the disaster which the battle of Stalingrad signified for the country of her birth, as well as for own family”. Beevor is the anonymous source for this sentimentalism.

Towards Chuikov, who also had a wife (right), Beevor cannot resist a parting shot at his moral inferiority and cruelty. This is Beevor’s very

last sentence: “The thousands of Soviet soldiers executed at Stalingrad on his orders never received a marked grave. As statistics, they were lost among the other battle casualties, which has a certain unintended justice”.

It is this conviction of Beevor’s that “justice” – placed seven times in Russian context, ironically – is on his side that also motivates and propagandizes the current American campaign for war against Russia. Today, this campaign proclaims the moral equivalence of Stalin and Stalinism for Putin and Putinism. The moral superiority of the Germans 79 years ago is now the moral exceptionalism of the Americans, especially of the two leading the American charge – Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Under Secretary of State Victoria Nuland (lead image, right). Their campaign is also a repeat of the German rassenkampf.

Sir Antony Beevor’s history of the battle of Stalingrad is a manual of how to fight the same old Russian evils without repeating the same old German mistakes.

NOTE: Beevor credits Lyubov Vinogradova with skilfully negotiating his access to the Defence Ministry archive at Podolsk; she is also thanked by Beevor as his translator from Russian over many years. In a 2021 interview, Vinogradova discussed the issue of access to classified military and intelligence archives. “To be honest, I think many foreign authors exaggerate the scale of changes in the Russian archives. All of them give researchers exactly the same material as they did in the early 90s, with the exception of the former KGB archive, which even in the early 90s did not give permission to everybody. Maybe a few more people were allowed then than now, but I think it’s normal for a secret service archive not to welcome all-comers. They [Russian officials] see themselves as successors of the Soviet Union and they keep these archives classified. I can see the reasons. I heard about a British researcher recently trying to get access to the MI5 and MI6 archives and he was denied.” Vinogradova has also published two histories of her own – one on Russian women fighter pilots in World War II (2016) and a second on Russian women snipers during the war (2017).

Leave a Reply