By John Helmer in Moscow

In outer space, as everyone knows, the absence of the force of gravity produces the appearance of weightlessness. Everything floats away.

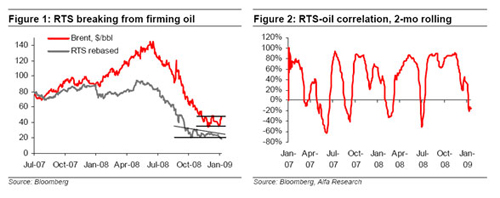

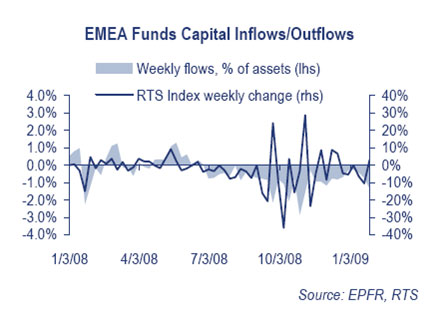

The markets have decided that Russia is now without gravity; its equities are without weight, and at risk of floating away. Late last year, the RTS, the principal stock market index, starting decoupling from the price of the principal Russian export, oil, as the latter started to plummet. The emerging market investment funds, which have also moved with oil and Russia’s other exportable commodities, also decoupled from commodity prices and the RTS. Since the start of January, the RTS and the oil marker have been in negative correlation. That means that even if the oil price goes up, Russian share prices go down. This is the equivalent of outer space.

It is no surprise, therefore, that everyone in the Russian market is gasping for an oxygen-mask, and a safety belt.

President Dmitry Medvedev and Prime Minister Vladimir Putin believe they are the constitutionally elected heads of government, and imagine their government is the air supply and safety-belt of the state. Those officials aligned with them — Deputy Prime Minister Igor Shuvalov with Medvedev, Deputy Prime Minister Igor Sechin with Putin — like to think that, although elected by noone to nothing, they too are the safety-belts, and pilots, of the state. Watch them closely — the more carefully Shuvalov brushes at his coiffure, and Sechin draws his face into a scowl, the more you can be certain they think they are in charge of Russia’s mass, motion, weight, air supply.

Without a banking and state audit system accountable to parliament, without a parliament accountable to the voters, and with regional governors and mayors appointed, not elected, where else can the force of gravity be located? If not with them, then all of Russia has indeed decoupled, and equity is in danger of valuelessness.

That is what these oscillating lines on the dials of the national control-panel mean:

In fact, once decoupling commences, there is no telling what the control-panel indicates for Russia’s pilot enterprises – the dominant exporters and producers of value, such as Gazprom (gas and oil), Rosneft (oil), Norilsk Nickel (nickel, copper platinum group metals), Rusal (aluminium), Evraz (steel), Metalloinvest (iron-ore), Polyus (gold), Uralkali (potash). That is because their public reports do not reveal the full extent of their debt; their shareholder stakes, pledges, and obligations; their margins; cashflow, and free cash; the ownership of their assets; their future.

Brokerage analysts, who try to measure these indicators, and issue buy/sell recommendations to the investment market, are now, more than ever, navigating by their own book — and shooting in the dark.

So are the principal enterprise owners and stakeholders, the so-called oligarchs. Each of them has now proposed to each of the senior government officials a plan calculated to cancel or refinance his debts with state money, but leave him in just as much control as before. This is the reason the market has been confused by as many state takeover or consolidation plans as there are oligarchs with billion-dollar obligations they can’t meet.

The evidence available from documents and inside sources close to the oligarchs themselves raises the following questions, and also answers them.

Why did Vladimir Potanin, controlling shareholder of Norilsk Nickel, place in a Monday morning newspaper on January 12 a scheme for merging Norilsk Nickel with steelmakers Evraz and Mechel,; iron-ore miner Metalloinvest, potash miner Uralkali, and vesting the lot in a new state company, in which Russian Technologies, the arms export-based state holding, would hold a 25% stake?

There can be no claim of stakeholder and management coordination, or raw material supply and production cost synergies, because Potanin didn’t consult the others, or come up with an integrated value scheme. The simple driver of Potanin’s plan was to create so much debt for the state to absorb, that he and the Norilsk Nickel group would be left to retain control of itself, and reduce the state shareholding in the scheme to 25%. The controlling stakeholders of the companies Potanin proposed to merge into the new state company have subsequently issued their refusals to go along. Each has his own plan.

Why did Oleg Deripaska, in a letter to Medvedev on January 20, invite the Kremlin to accept a $45 billion valuation for Rusal, and issue $6 billion in state loans to cover part of Rusal’s debt, in return for an issue of 15% non-voting shares in Rusal, and a promise to pay the state dividends — if and when aluminium prices rise enough for Rusal to declare a profit? Again, the answer is that Deripaska wants a bailout with minimum loss of control for himself.

Asked why the Norilsk Nickel consolidation plan didn’t have room for Deripaska’s Rusal, Norilsk Nickel’s chief executive, Vladimir Strzhalkovsky, has responded he isn’t seeking a merger with Rusal because the aluminum company has too much debt. As it stands, the proposal from Potanin would pool $28 billion of debt to $60 billion in sales, according to Interros, Potanin’s holding company.

Just a little memory is required to see this as a reprise of the very first state bailout, which made Potanin and the other oligarchs what they became, and what they are today. In 1995-96 that was called loans-for-shares. It was the scheme by which the state treasury loaned the oligarchs money for cut-price privatization of the control stakes of the natural resource assets they incorporated as their own. Having leveraged these shareholdings in the dozen years that followed, in order to create even larger conglomerates inside Russia, and parallel asset empires in safe-havens abroad, and having squirreled away billions of dollars in personal dividends, they have come back to the government with a request to play the same game all over again.

According to one oligarch, he is disappointed to find there is no government where he expects to find it, only bitter rivals at each other’s throats. What he means is that it was much easier, and also cheaper, when he had to deal with President Boris Yeltsin.

A lesser known, but oligarch-sized figure, Vyacheslav Kantor, controlling shareholder of Acron, a fertilizer producer and exporter, submitted his plan to Putin and Sechin, just before they appeared for an inspection of his Novgorod factory on January 25. Kantor’s scheme puts himself in control of a state-financed company that would take over mining licences Kantor has borrowed to buy and develop, but which he cannot afford any longer. He is asking for a bailout of $700 million of debt, and a credit line from a state bank of up to $2 billion for his mining undertakings. In this Acron scheme, the state equity stake in exchange would be a non-controlling one.

Other schemes that have been tabled at Sechin’s office in the mineral fertilizer sector indicate the creation of a state company to consolidate existing state stakes in phosphate and potash companies, and impose a fine on Uralkali, owned by Dmitry Rybolovlev, which would oblige him to give up his stake in his company.

Alisher Usmanov, the controlling shareholder of the Metalloinvest group, said he is opposed to the mega-merger of Potanin, because it under-values his own assets, and dilutes his control. Usmanov said on January 28 that one option he prefers is a scheme of merger between Norilsk Nickel and Metalloinvest without a significant stake stake. Alternatively, to absorb his own debts, he offers a scheme incorporating Metalloinvest, Norilsk Nickel, and steelmaker and coal-miner Mechel, plus diamond-miner Alrosa. Announcing the obvious, Usmanov has said: “If the Russian government would participate in this merger and restructure the debts of the companies everybody would win from it.”

A frank admission from one oligarch headquarters: “This global [state] company would be impossible to manage, it is true. But the reasoning here is that this is a measure only for the crisis period. Later, each of the companies would be able to buy back their shares from the state, and separate again.”

The presumption of all these plans is that, if and when global demand recovers, commodity prices revive, export revenues grow, share prices pick up, and the international capital markets can accommodate Russian debt financing needs again, the oligarchs would borrow abroad to buy out the state – and resume the same unconstrained control of their enterprises as they enjoyed before all the trouble began. That’s a big if; the when may be a long time coming.

Putin has responded ambiguously in a lengthy interview on January 25: “First, there are no final decisions here. Second, what you’re speaking about was suggested by the owners of these companies. But you know that if you get two poor people together, it won’t be a richer family. So it all depends on the specifics. Where there can be any positive synergy from consolidation – say, when one party has mineral resources, the second has financial possibilities, and the third has access to the markets – it will be in demand. You don’t need a lot of brains to combine debts with debts, and it won’t bring any results. That’s why we’ll keep a balanced, careful approach to this problem. Once again, the main goal here is to increase competitiveness.”

But the same day Putin also said he favoured Kantor and his plan: “The owners of this enterprise [Kantor’s Acron] not only keep jobs in quite difficult conditions, they also develop the social sphere. Owners of the enterprise are not poor people. If those who deal with real production also have a feeling of social responsibility, we will support such people.”

Then in Davos, on January 28, Putin declared: “Excessive intervention in economic activity and blind faith in the state’s omnipotence is another possible mistake. True, the state’s increased role in times of crisis is a natural reaction to market regulation setbacks. Instead of streamlining market mechanisms, some are tempted to expand state economic intervention to the greatest possible extent.”

“The concentration of surplus assets in the hands of the state is a negative aspect of anti-crisis measures in virtually every nation. In the 20th century, the Soviet Union made the

state’s role absolute. In the long run, this made the Soviet economy totally uncompetitive. This lesson cost us dearly, and I am sure nobody wants to see it repeated. Nor should we turn a blind eye to the fact that the spirit of free enterprise, including the principle of personal responsibility of businesspeople, investors and shareholders for their decisions, has been eroded in the last few months. There is no reason to believe that we can achieve better results by shifting responsibility onto the state.”

As clear as this looks, its application is anything but. Hence, the dislocation between what Russians say, and what the market does.

Sechin has been quoted by Interfax as saying that the decision on the consolidation plans is up to the shareholders. If that were believable, Rybolovlev of Uralkali would be relieved that he will be deciding the future of the potash miner, not Sechin. But at Uralkali headquarters in Moscow, and in Geneva where Rybolovlev is based, it is the state shareholder, and Sechin’s fiat, which are expected to decide. This is why Uralkali’s share price is at a substantial discount to its peers, at home and abroad; and why its downward trajectory is disconnected from the potash commodity price.

Deputy prime minister Shuvalov has said: “We see that many enterprises that we work with, and their shareholders, have started to feel that the state will save them no matter what. Against this background, they have begun to think … that the state will help them no matter, help them to refinance their foreign debts and give them special programs to buy their production. We have nothing like this in our plans. Just because the enterprise is important and has several tens of thousands of workers, we do not simply intend to give out resources and wait for them to come for more later. The shareholders and heads of these enterprises must for themselves look at their own personal responsibility.”

Those oligarchs who are uncomfortable with state takeover risk, and think they can refinance from the same international banks, to which they are already mortgaged, are now trying to escape. One of them, Igor Zyuzin, owner of Mechel, is well aware that he’s on others’ hit-lists. He and Alexei Mordashov, controlling shareholder of steelmaker Severstal, are reported by bank analysts and industry sources as having decided to pull back last month’s applications for state bank loans. Since they don’t admit to lodging their application; the state bank won’t say if applications have been lodged; and noone will acknowledge whether the state bank said yes or no to Zyuzin and Mordashov, there is no way of gauging whether Zyuzin and Mordashov are today more or less desperate. The international markets are in two minds — Severstal’s share price is up 10% over the past four weeks; Mechel’s is down 21%.

If Putin means what he was saying in Davos, this is exactly what should be happening for the greater benefit of all. “The constant temptation of nestling close to the sources of state well-being is perfectly understandable,” the prime minister told the Davos audience. “But at the same time, these sources are not inexhaustible, nor are they cure-alls.”

But Putin will not return to Moscow to tell parliament which of the oligarch enterprises will be saved by state financial guarantees, budget funds, or state bank cash. Nor will state auditors and valuers be allowed to testify to parliament on the terms of the new round of loans-for-shares. These are state secrets. And the funny thing about state secrets is that in the marketplace, outside the state, they perform like heavily discounted promissory notes.

In due course, the market will get Putin’s message from the enterprise shareholders. It will discount the value of what they say.

In the meantime, the market will apply the outer-space discount. That deals with the risk of not being able to anticipate anything at all. Uncertainty and fear are now making Russian assets worth less than they were during the last two national crises – in 1991, when the Soviet system collapsed; and in 1998, when the Treasury and the banking system defaulted.

Leave a Reply