By John Helmer, Moscow

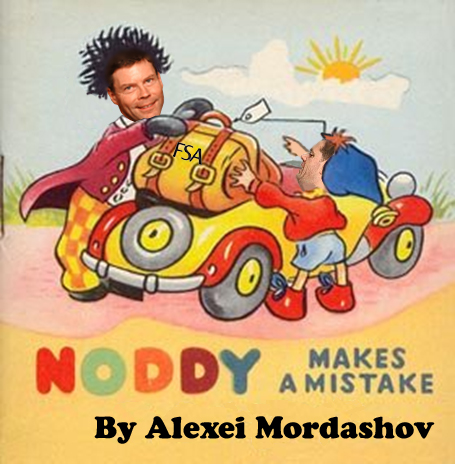

Now children, this is a story of the boy who was so keen to go on holiday, he packed his bag too soon.

The three insiders familiar with the matter, on whom Bloomberg relies, seem to have got the story wrong, at least so far as the timing of Alexei Mordashov’s (right image) initial public offering (IPO) of Nord Gold shares. They were reported as saying last week that the company had lodged its application to the Listing Authority of the Financial Services Authority (FSA), the London regulator headed by Hector Sants (left image): “OAO Severstal’s gold-mining unit is seeking regulatory approval for a $1 billion initial public offering in London, according to three people with knowledge of the plan. The IPO, managed by Credit Suisse Group AG, Morgan Stanley and Troika Dialog, may start as early as this month, pending approval from regulators in London, two of the people said, declining to be identified because the information is private.”

This is wrong, because three other people familiar with the matter say the IPO will not be taking place this year. While they say the reasons are not yet clear, the suspicion in the marketplace is that the postponement has been forced by delays in approving the share sale at the FSA. The three sources are investment fund managers and bank analysts in the US and Russia, who haven’t been talking to each other. One says: “we are hearing that the London listing of Severstal gold assets (Nord Gold) could be postponed till 1Q11 due to some delay in FSA approval of the IPO.” The second says: “I have heard rumors of a delay, but have not heard why.” According to the third: “The possibility that the IPO could be pushed back into 2011 was cited by the management about a week ago, though they were talking about stock market conditions as a possible reason.”

Severstal Resources, the mining arm of the Severstal group, made its last official announcement on September 24, when it said: “Severstal Gold N.V. (“Severstal Gold”), a subsidiary of OAO Severstal (“Severstal”) (LSE: SVST; RT CHMF), is pleased to announce that that it has acquired 3,900,000 common shares (“Common Shares”) of Sacre-Coeur Minerals, Ltd. (“SCM”), at an average price of CAD$1.5444 per Common Share, as part of its plans to acquire SCM. The purchase takes Severstal’s ownership to 19.67% of the issued and outstanding Common Shares of SCM.”

Severstal Gold, an Amsterdam-registered subsidiary, has subsequently had a name-change to Nord Gold, at least according to Bloomberg, which has reported that “the gold unit, Nord Gold NV, will be valued at $4 billion to $5 billion after the sale.” Nord Gold is an odd choice of name, because most of the company’s gold reserves are in the Sud; that is to say in Africa.

The only other, albeit indirect reference by Severstal to Nord Gold is the release yesterday of trading results for the third quarter. These indicate that gold production by the company’s mines reached 148,412 troy ounces by September 30; that makes 8% growth since the second quarter. And more money was coming in too, because the average sale price of Nord Gold’s gold is reported to have grown 4% on the quarter to $1,238 per ounce.

Now children, you can’t blame Noddy for thinking that if the sun is shining brightly, it must be time to take off, at least to be sure he will arrive before the rain starts to fall, as it usually does in England. All this week, the streets of London and the English countryside have been packed with other children on their school holiday. So why is Noddy being left behind?

The gold price continues to shine like this:

Not even children should blame Bloomberg for sounding like a holiday brochure, if its reporters write down what they are told without checking with the weatherman. Regarding Nord Gold, Bloomberg has reported: “The IPO, if successful, would be London’s biggest since Nathaniel Rothschild’s mining fund Vallar Plc raised $1 billion in July. The sale would also be the largest overseas share offering by a Russian company since Moscow-based United Co. Rusal raised $2.24 billion in Hong Kong in January.”

So what to make of the fact that Nord Gold is delaying the sale of its shares past the year end?

“We don’t comment on the approval process,” a spokesman for the FSA says, making clear that no public record is released of companies which submit their prospectuses for approval by the FSA’s Listing Authority. Announcement of the intention to float (ITF) is up to the company to announce, the FSA spokesman explains. “It is up to the company to issue its prospectus. When it does, that indicates that the ITF has been approved.”

Since Bloomberg’s insiders are inside Severstal’s IPO team, and have been making Mordashov’s ITF apparently crystal clear, the absence of the prospectus and of the official ITF can be read as confirmation that there has been no approval of the listing. Not yet.

This may be bewildering to young readers. Why would Noddy pack his bag and load his car, but not drive off? That’s easy to explain — because he has made a mistake. What sort of a mistake Mordashov has made is not so easy to say. Asked to clarify the intention to float, the spokesman for Severstal Resources, Sergei Loktionov, does not respond.

By the Bloomberg standard, if Mordashov cannot list Nord Gold now, when it seems he wanted to, and when the gold price is optimum, what size of failure would it be for the share float to be postponed for undisclosed reasons? Would the failure be as big, for example, as the share price collapse for Rusal on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, when the share dropped 38% after the January 27 listing? Or as big as the debut of IRC Limited, the titanium and iron mining vehicle of Peter Hambro and Pavel Maslovsky, which was forced to reduce the number of shares it proposed selling on the Hong Kong exchange; and then when it did list on October 18, it suffered a 9.4% decline in price? Is the news as bad as the failure of Mikhail Prokhorov’s Polyus Gold to achieve its London listing by merging with and reversing into Kazakh Gold (KazGold)?

On October 26, Polyus Gold cancelled this transaction, after negotiations failed between Prokhorov and the Assaubayev family, former controlling shareholders of KazGold, over claims of misappropriation of shareholder funds, fraud, and other problems. Litigation continues in London and in Kazakhstan over the conflicting claims. Other claimants are also in arbitration against KazGold in London. The bill alleged runs to more than $250 million. But questions have arisen on the Kazakh side over what Prokhorov and his men knew and did about the financial operations of KazGold, long before the recriminations became public.

A report by Rensissance Capital, the Enid Blyton of the Russian investment market, says the failure of the KazGold plan “compromises Polyus’s plans for a London listing, the achievement of a global acquisition currency and potential for global M&A. The biggest driver for Polyus is the success of the Russian growth strategy. On the corporate front, we believe Polyus needs to be a lot more convincing on execution.”

For convincing, children, you may not want to rely on what the New York Times has to say about Prokhorov in a profile published on October 28. That’s because there are so many American children who support the basketball team Prokhorov recently purchased. The basketball team has been playing so woefully for so long, they are bound to sympathize with the story of childhood fears and food deprivation in the Soviet Union, which Prokhorov trotted out to the Times. It also seems that so fearful was little Prokhorov of reading books forbidden by the Soviet censor, he admitted recently, as the Times quotes him: “I don’t read.”

O No! O Noddy! So much depends on oligarchs in the goldmining markets telling the truth to their shareholders. But if they don’t read what is published on their behalf, they may make mistakes.

But can these Russian goldminers also count? The New York Times report on Prokhorov reveals a number which has been more closely guarded than many of Russia’s state secrets – that’s the amount of tax Prokhorov pays in Russia. The purchase price for the Nets basketball franchise, including debts, other obligations, and a stake in an associated Brooklyn stadium and real estate development, came to $425.6 million. According to the intrepid Times reporter, “what he paid for the team was less than what he paid the Russian government in taxes last year.” And elsewhere in the same report: “Prokhorov’s official residence is a village in the Krasnoyarsk region of Siberia, where he pays upward of $500 million a year in taxes.”

Polyus Gold, Prokhorov’s principal cash-earning asset, reported paying $109 million in income tax in 2009; Prokhorov’s share of Polyus Gold is about 40%, so his share of the tax might be calculated at $44 million. Rusal, in which Prokohorov has a 19% stake, paid just $18 million in tax for the year, so Prokhorov’s share might be counted at $3.4 million. Total comes to less than $50 million. So how can it be that Prokhorov pays ten times that number at his tax residence in Krasnoyarsk?

His spokesman Igor Petrov responds: “I would like to clarify this figure. The interview, or rather the journalist’s statement, is about the Tax on Individual Person’s Income, which Mr. Prokhorov paid for the 2008 fiscal year. It was just the time when transactions involving asset partition between Mr. Potanin and Mr. Prokhorov took place. So that was practically the peak of his income tax payments.”

Leave a Reply