By John Helmer, Moscow

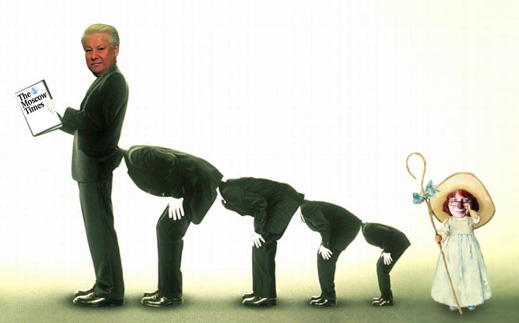

Journalists arranging tuxedo events to give themselves prizes are even sillier than Hollywood actors at the Oscar ceremony. There are also no comedians to tell jokes to neutralize the gastroenteric reflex that is always brought on in audiences by a surfeit of brown-nosing. For the British children in the audience who don’t know what that term means, the Private Eye term is the more onomatopoetic — arslikhan.

Meg Bortin, the second editor of the Moscow Times and one of the shortest termers, has been rolled out for today’s celebration of the 20th anniversary of the Times. The true anniversary actually fell in March, eight months ago. But if that was the point from which to hang the anniversary celebration, Bortin couldn’t call herself the “founding editor in chief”.

She’s also awarded herself the job of rewriting Russia’s past and future, and demonstrate how brown her nose still is. “The question for the next 20 years, “ she opines in today’s edition, “is whether the paper can retain this independence — a willingness to look at the news in Moscow and Russia and tell the truth, even if that truth is sometimes displeasing to the authorities.”

This is mock-bravery. The authorities Bortin recognized in Moscow at the time – the ones in residence at Spaso House – were the only ones she dared not, never thought of displeasing. She also ran an editorial policy that dared not controvert their policy. Bortin reserved special venom – the adjective “pro-communist” – for the Congress of People’s Deputies, elected two years earlier; its Speaker Ruslan Khasbulatov; and the executive chamber then known as the Supreme Soviet. Bortin knew none of them; had no sources in the factions or the party leaders’ offices; and detested them all, insisting that the reporting of the Times should depict them and their debates as anti-democratic, communistic, anti-American, etc., etc.

In April of 1992, the Congress had overwhelmingly rejected then President Boris Yeltsin’s attempt to take emergency powers. It had also approved the draft new Russian constitution prepared by the Constitutional Commission led by the very young lawyer, Oleg Rumyantsev. By September, Rumyantsev’s draft for a parliamentary republic of roughly the French type, was headed for enactment if and when the Congress was reconvened. That should have been in October, as had been planned.

That session was also certain to reject the economic policy programme (“reform” in Bortin’s list of approbative nouns) delivered to the Kremlin by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), through Yegor Gaidar, then half-way through his six months as acting prime minister. Detested throughout the country, Gaidar was another of Bortin’s approbative nouns.

The showdown between Bortin and I came on September 1, 1992, after I had filed a 12-paragraph news story, entitled “Khasbulatov postpones People’s Congress session.” Read the original despatch here. My sources were from Speaker Ruslan Khasbulatov’s office; from the Congress factions; from staff in Gaidar’s office; and from the Kremlin. The big news was that Khasbulatov had decided not to allow the Congress to resume its session in October. The significance was that he was postponing the conflict of powers between the executive and the legislature. Khasbulatov thought, the story reported, that he was buying time to give Yeltsin more rope to hang himself; the president was polling 30% or less approval in Moscow at the time. Khasbulatov thought the showdown would come eventually, but he wanted to appear to be keeping himself above the fray, and mobilize a cross-party consensus behind the new constitution. If the time came to drive Yeltsin from power, Khasbulatov thought it could, and should be done constitutionally. In retrospect, Khasbulatov’s misjudgement was colossal. In time he has admitted it.

Bortin, though, didn’t understand then, has never understood what was happening. But she wouldn’t allow my little news story to run. She would also brook no direct-source reporting from the congress, the constitutional commission, or the parties then in opposition to the president. That led to that showdown of all showdowns in newsrooms the world over – the showdown over the truth. It also led to a brief but noisy episode of clinical hysteria from Bortin, and a confession from Bortin’s publisher, Derk Sauer, one of the Dutch co-owners of the Times.

Bortin had been an embarrassment to Sauer, which he apologized for, telling me that an American national was necessary to secure the funding on which the Moscow Times depended. I was polite enough not to enquire what funding he was talking about; I already knew. The occasion was that I – now the only (American) reporter from the original team under the first editor, Michael Hester, still at work in and on Russia – had refused to attach the required derogatory adjectives to the parliamentary opposition to Yeltsin, and refused to report the IMF programme with the required noun, “reform”. Not even my sources at the IMF Moscow office, including the French protégé of IMF Director Michel Camdessus, accepted that guff from Gaidar. But Bortin did, so she fired me on September 3, 1992. Sauer then rehired me with an increased salary to be paid each month on condition I didn’t report what had happened, and didn’t join the competition.

In 1994, after two years at the Moscow Times, Bortin went off to a sanatorium in Paris. She reports in her blog that she is writing a memoir called Desperate to be a Housewife and a manual called The Everyday French Chef. It’s been a case of – if you can’t stand the heat, go to the kitchen.

After her exit, Sauer’s US money began to dwindle, so he applied to Mikhail Khodorkovsky to keep the Times’s press rolling. Khodorkovsky’s money was followed by other oligarchs, and some especially Russophobic Finns, until now Sauer himself is reported to be contemplating enrolment in the ranks of Mikhail Prokhorov, in a unit as elite as Muammar Qaddafi’s female battalion once was, if not quite as handsome.

Bortin missed out. It takes chutzpah to claim that “when the first issue of Russia’s first independent English-language daily came out the next morning — on Friday, Oct. 2, 1992 — no one could have imagined the impact The Moscow Times would have in the months and years ahead.” The only accurate term in that account is “daily”; the Moscow Tribune was in English, and had been coming out independently, but weekly, for more than two years earlier. As for the future conditional about noone imagining what impact the Moscow Times would have, the only word Bortin got right there is “noone”. That’s because the Times has been wrong on every major position it has taken over the past twenty years. It hasn’t been independent; it hasn’t had any impact. It is neither as cleverly comic, nor as linguistically memorable as The Exile, whose editors, Mark Ames and Matt Taibbi, have been erased from Bortin’s 20-year anniversary roll.

For all these years then the Moscow Times has been to Russia as ersatz coffee was to Germans during World War II. You might say that if you start a war and lose it, you deserve to have ersatz coffee instead of the real thing. Those who think the Moscow Times is the real thing have lost their war, but can’t be weaned off their taste for their ersatz. From nose to mouth in twenty years – not far, no taste.

Leave a Reply