By John Helmer in Moscow

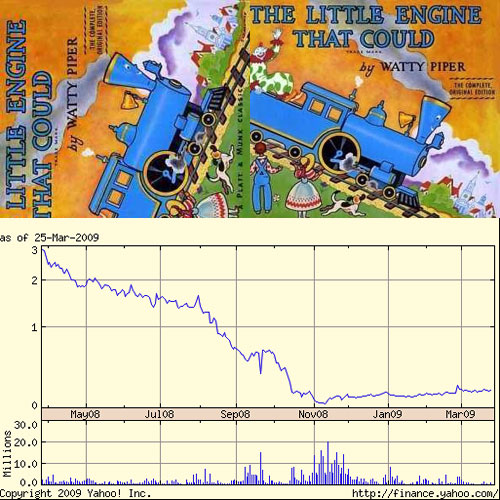

In 1930, at the start of the Great Depression, a story was published in the US with the purpose of convincing children that if they worked hard, they would be rewarded. That idea being none too original, it turns out that the tale of the small anthropomorphic locomotive, who pulls a heavy line of freight-wagons over a mountain-top, was cribbed from a publication a quarter of a century before.

If your mother read it aloud to you as a youngster, you’ll remember the best parts. The first was at the shunting yard when the bigger locomotives refuse the job, and the little one chants: “I think I can. I think I can. I think can.” With tantalizing tension as he slows on the up-grade, he manages the feat, and then celebrates as he runs downhill: “I thought I could. I thought I could. I thought I could.”

High River Gold (HRG:CN) is the Toronto-listed junior who’s lived to tell this tale. Only the children in the market don’t appear to have heard it, yet.

With four operating gold mines in Russia and Burkina Faso, tw and two mine projects in development, HRG has currently attributable production of about 300,000 ounces per annum, and is cashflow positive. Attributable gold reserves were estimated in February by Dan Hrushewsky, HRG’s investment relations director, at 2.2 million oz, with silver reserves at 5.2 million oz. A subsequent release from the company on March 17 reported a MICON expert audit of gold reserves at the Zun-Holba and Irokinda mines (Buryat region of southeastern Siberia). Altogether, counting the Bissa gold project in Burkino Faso and the Prognoz silver project (Sakha region of fareastern Siberia), and converting silver reserves into gold equivalent, HRG’s gold equivalent reserves and resources, on the Canadian NI 43-101 basis, add up to 6.1 million oz.

A recent international investment bank valuation of HRG estimates it at almost $770 million. The current market capitalization, however, is C$112 million (US$91 million). This compares with Russian peer Polyus Gold (PLZL:LI) at $9.1 billion; Polymetal (PMTL:LI), $2.2 billion; Peter Hambro Mining (POG:LI), $686 million; and Highland Gold (HGM:LI), $203 million.

HRG’s last financial report indicated that as of September 30, the company was in trouble. Gold production in the third quarter had dropped to 33,460 oz, down 2.5% compared to the same quarter of 2007; cash operating costs had jumped 42% to $546/oz. There was a net loss of $15.3 million for the quarter; a loss of $22.4 million for the nine-month period. Some of HRG’s mine loan covenants were in technical breach. That was the bad news. There was worse. According to a company statement, “on August 1, 2008, High River announced a strategic investment transaction with an indirect wholly-owned subsidiary of the Alfa Group Consortium (“Alfa”). Due to a subsequent deterioration in market conditions the transaction was cancelled.” Between February and September of 2008, the share price plummeted from C$3.50 to 46 Canadian cents. Accumulated debt was $189 million. The failure of the Alfa plan meant that $286 million in promised financing had vanished.

The quarterly financial report acknowledged: “High River is currently facing a liquidity shortfall….The ability of the Company to continue as a going concern is therefore dependent on the on-going discussions and/or forbearance with the lenders, accommodations from trade creditors, establishing steady production at the two new mines and obtaining additional financing. There is no assurance that the lenders will cooperate with the Company, that trade creditors will provide accommodations, that steady production can be established or that a financing or other transaction can be completed on terms acceptable to the Company.”

As little locomotives go, this was hardly a case of “I think I can.”

Then the good news started. In November, the Severstal international steel and mining group, controlled from Moscow by Alexei Mordashov, bought a 53% stake in HRG for $45 million. Severstal then began to restructure the company’s opereations and financial position, repaying some debts and securing improved terms from banks, which include Nomos (Moscow), Unicredit, and Standard Bank (London).

The debt overhang and technical mining problems, which had driven the miner to the wall, appeared to be clearing. However, despite an initial flurry of demand for the shares at the time of the November takeover, HRG’s share price has moved slowly. Although it has moved upward from 4 cents just before the Severstal deal to 19 cents this weeks, a pick-up of 375%,, the low base at which it started has kept HRG from realizing what some gold analysts observing the Russian sector believe to be its potential.

A London analyst responded that “the market price prior to the Severstal intervention and debt restructuring had priced in liquidation. The move off this level may look very large, but it’s off such a low base the percentage movement means little.”

A Canadian market source was asked why he thinks the market is discounting HRG more heavily than the other Russian goldminers, and why HRG’s recovery is relatively slower? He replies: “A couple of things come to mind. First of all, liquidity. In covering the North American gold producers I have found that liquidity demands a far greater premium right now than it has over a typical cycle. With Severstal owning 53%, that leaves only about $40 million in free float, so I wouldn’t expect HRG to match the valuation of larger peers. Secondly, I’m not sure how those other stocks are performing on the technical/production side, but HRG has been plagued with technical problems, particularly at its two new, supposedly better mines, and has not been able to post any free cash flow for many quarters. With that technical risk still there, HRG should be discounted.”

On March 26, the last day of trading before this was written, HRG’s share lifted by 12%, its largest one-day gain since late February, when it jumped by almost 60%.

Leave a Reply