By John Helmer in Moscow

Many things can make a person greater than he or she really is, except time.

Time activates the bacteria that strip the flesh off the bones, until only a forensic pathologist can detect the tiny signs of individuality; and even they add up to nothing more than a catalogue of pain and death.

Time unravels the outcomes of all endeavours. The maddest passions, the wildest exploits, the most ruthless ambitions, the most victorious strategy – all lose their genius in time.

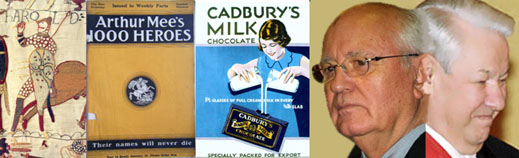

I was brought up on the reverse. I read, and accordingly was certain, that mankind produced heroes whose deeds outlived themselves. Even small deaths, the ones we as schoolboys used to stand at attention to remember twice or three times a year, defied time. The evidence of that was surely that we were standing there saluting, wasn’t it?

As I grew older, I became more skeptical, until today, a few hours before the end of the millennium, I look back and contemplate the bones of my ancestors. In politics, are we all losers? I ask myself.

The first event concerns my middle name, Harold. It has been such an embarrassment all these years that I got rid of it from my passport as soon as I could. In 1066, it was the name of the Anglo-Saxon king who lost the decisive battle of Hastings to a Franco- Norman king named William. Harold, with such an expansive, multisyllabic, tongue-rolling ring to it, beaten by a mere Bill. Improbable sounding, isn’t it?

And it never would have been, except for the unlucky circumstance that, as Harold sensed victory within his grasp and charged downfield to destroy his foes, he looked skyward, and an arrow shot him in the eye. O unlucky Harold, to cop it so ignominiously, and lose the field to William.

That was enough for me, too. I became plain John. Never mind that the next Englishman to lose an eye in battle with the French, thrashed them; and with a name like Horatio to boot. Can we say that time was on Harold’s side, and revenged him through Admiral Nelson? Only if you are a French-hating Englishman – and I’m neither.

In the years that followed the death of my namesake, and the loss of his homeland, I look back and see precious little that time has kept alive for me. In 1596, William (another lucky one) Shakespeare wrote “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”, which has taught me everything I need to know about love. Especially the part that when you are in love, your judgement is as good as a donkey’s.

I say this, not to offend the people I love – because I truly do love them – but because I’ve also been inclined to love the things that we were taught as schoolboys were worth loving more than lovers, or life itself. Things like flags, uniforms, territory, countries, honour, glory, etc., etc. Shakespeare’s “Dream” is a regular reminder not to fall for those spells.

Almost a century after the play, there was another invention that has done even better in the millennium than Shakespeare. In 1687, Hans Sloane, an English physician on the island of Jamaica, discovered something he called nauseous and indigestible, which could be transformed if he mixed it with milk. This was chocolate.

Giacomo Casanova, in the next century, was as religious about keeping a stock of it for his breakfast as he was about washing himself. Casanova was the only Italian this millennium those ideas of love and hygiene were neither perverse nor a joke. In the previous millennium he had some serious competition among the Romans. But if the next millennium is like more of this one, he will remain the only Italian whose vanity didn’t exceed his accomplishments. But what time has done to him is unfortunate. He is famous for what he wasn’t. His reputation encourages his countrymen to ape with women what he scorned. As unlucky as Harold!

I once wrote a speech for a powerful politician, who climbed out of bed with one woman, and into bed with another; and wanted to assure the country he hadn’t lost his head. An election was coming up, and the polling showed that women voters were angry.

Of course, Casanova’s name was anathema; and in any case, in that country, Italy wasn’t exactly a friendly power. I went back to Shakespeare, to the madness of Othello, not to the fun of Puck and Bottom.

The politician was the only man I have ever loved, and though the speech was about his heart, it was about mine too. He didn’t understand the part about heartbreak or betrayal. He also didn’t give the speech the way it was intended. But he did try a few of the lines in an interview with a magazine for teenagers, who couldn’t vote.

He didn’t exactly lose the next election either, but he misjudged the votes badly. He thought he was in love, but his judgement had fallen under a spell. In time, that caused him to lose his reason, and destroy every shred of trust anyone could have in him. And when he realized that, I’m told he begged the doctors to let him die, and was tortured when they wouldn’t.

It isn’t pleasant to watch a once powerful man crying for the mistakes of his life; crying for the time to make more; and crying for release. But a thousand years of time drowns out these sorrows. Better to say it combines them, and turns them into a flood, which, as it recedes, leaves a permanent and ugly stain.

Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin have justified the damage their political rivalry inflicted on Russia in many ways. But none of their claims is as stunning as Gorbachev’s explanation for his defeat. Perhaps he should have destroyed Yeltsin, Gorbachev has said, by packing him off to an embassy in Africa. But he didn’t, in order to demonstrate the civilized reform he was intent on bringing to Russia. “With Yeltsin”, Gorbachev has said, “I ended up a victim of my own principles.”

Not even the hapless Harold, looking upward as the fateful shaft descended, could have thought up, in a few seconds, such a colossal self-serving lie. And even if he had, it was too late. He was dead before he could say it.

Time, which is already picking at the bones of the two Russians, is always more merciful to the silent. But forgotten they are, just as surely.

First published in The Moscow Tribune, December 24, 1999

Leave a Reply