By John Helmer, Moscow

Swiss bankers aren’t famous for their sense of humour. So it will come as no surprise that the Gnomes of Zurich were serious when they recently sent a questionnaire to 22 of the richest crooks and liars in Russia, asking them for their assessment of the prospects for Russian wealth management — and printed their answers with a straight face. According to UBS, 55% of their 22-person sample say corruption is the biggest problem they currently have in increasing (or keeping) their wealth; well ahead of macro-economic problems like falling demand; global problems like the collapse of commodity prices and producer share prices; and domestic commercial problems like the weakening rouble, rising costs, and dwindling bank credit.

The twenty-two made the UBS sample if they were domiciled in Russia and admitted to a net worth of at least $50 million apiece. One in 10 of the sample (that’s two) “belong to families worth between $250 million and $500 million, with one family worth in excess of half a billion dollars.” Of the remaining 20, 13 reported a family fortune of between $50 million and $100 million. Three put themselves in the wealth bracket between $100 million and $250 million. Richer crooks and liars may have returned the UBS questionnaire unanswered. But those responding acknowledged that when it comes to running their businesses and making money, they don’t give a fig for accountability, transparency, or the conventional standards of corporate governance. According to the report, “the percentage of respondents adhering to a corporate governance code has fallen substantially to just 23% [five]. Of the remainder, 41% say they are in the process of implementing a code, but 36% simply state that they do not comply with any corporate governance code.”

The report concedes that last year’s sample may have been fibbing, as this year’s sample is telling the truth when they imply that lying to shareholders and clients doesn’t matter. “[In] last year’s survey 74% said they were adhering to a corporate governance code and a further 21% were planning to implement a code, with the remainder claiming to be in the process of implementing a corporate governance code in their company.”

UBS conducted its research with Campden Wealth. Its specialty, according to the company website, is selling “unrivalled knowledge and intelligence to a community of the world’s wealthiest families, their family offices and ultra-high net worth investors.” Think of this as a newfangled Masonic Lodge – “families connect directly with each other in a private peer-to-peer environment providing them with unique access to innovative educational and networking resources worldwide…business-owning families of substantial wealth and family offices trust Campden to deliver world-class peer-to-peer networking events, proprietary, groundbreaking research and cutting-edge magazines and websites, which are vital resources to their future success.”

The London-based parent company called Campden Media says its business is “serving the ultra high-net-worth, multigenerational family community”, but doesn’t say who owns it. And so there’s no way of telling whether this is the billionaire’s equivalent of the Nigerian Letter Scam (aka the Spanish Prisoner). A copy of last year’s Russian “Wealth Creators Survey” can be purchased for between £1,995 and £2,495, depending on the format. A ticket through the closed door of “The Russian Wealth Creators Forum”, scheduled at a Moscow location later this week, can be reserved if you hit the booking button here, (naturally, you’ll need to reveal your private details in return for a secret password.)

A check of the UK company register reveals that Campden Media is a private shareholding company registered seven years ago. It was loss-making in 2009 and 2010. Last year it declared a profit of almost £366,000 on turnover of just over £10 million. Its current net worth is negative, because its liabilities of £6 million exceed its assets of almost £4 million. The shareholders include the two founding executives, John Pettifor and Kevin Grant, and four company or trust shareholders, one of which appears to belong to Pettifor, the managing director of Campden Media.

Andrei Postelnicu at Campden Wealth is the principal author of the new report. Here is the full text. He declined to clarify how the 22-member report sample was drawn from what the report calls an earlier sampling of “successful entrepreneurs domiciled in Russia.”

Note that Campden was able to recruit 19 people to answer the “wealth creators survey” in 2011, and three more in this year’s survey to make 22. That makes a growth rate of 15.8%. Russia’s industrial growth rate, on the other hand, is decelerating in the opposite direction, according to the latest Rosstat report; it is trailing the UBS-Camden “wealth creators” by a factor of 752.4%.

Inside the secret precincts, does that mean Russia’s candidate oligarchs are quietly congratulating themselves on picking up fresh assets on the cheap and getting richer, while everyone else gets poorer?

Inside the secret precincts, does that mean Russia’s candidate oligarchs are quietly congratulating themselves on picking up fresh assets on the cheap and getting richer, while everyone else gets poorer?

Gregg Robins might know, because he is the head of private wealth management at UBS’s Moscow branch. Robins told the Moscow Times that “sources of liquidity have become scarcer, and … international markets are becoming more difficult.” This intelligence is positively Nigerian.

But is it a scam? Suleiman Kerimov’s case is indicative because he is one of the most reputable oligarchs, trusted by a great many Russians of high rank and ultra-high personal worth themselves to manage their private equity investments. For them, and for himself, the business history shows he has generated ultra-high rates of return on the purchase and resale of shares in Gazprom, Sberbank and Polymetal; lower rates of return at Uralkali and PIK; and negative rates of return at the late Fortis Bank.

At the moment, it’s Kerimov’s position at Polyus Gold, Russia’s largest goldminer, that is being tested. Listed on the Moscow and London Stock Exchanges, the Moscow share price for Polyus (PLZL:RU) is currently less than half of its peak over the past year, with a market capitalization of $6.2 billion. If Moscow sentiment deteriorates, it could drop to the low reached during the 2008 commodity crisis, when its market cap was less than $3 billion. By contrast, in London Polyus Gold International (PGIL:LN) is looking better, with a market cap of £6.7 billion ($11 billion). Strictly speaking, the Russian-listed share can’t be compared with the London-listed share because the former has a narrower asset and shareholder base, is less liquid, and may not share in dividends, buybacks or takeover premiums available to shareholders in the London entity. On the other hand, the relatively greater pessimism in the Moscow market may be a more accurate sign of what is coming for the company.

When commodity and share prices become volatile, lurching downwards, it’s natural for banks which lend to the oligarchs on the security of forward trade flows and past market capitalizations to make margin calls. This is standard practice to compensate the creditor for the growing risk of default and reduce the gap between the asset value when loans were issued and secured, and the recoverable value right now. Kerimov has been caught in this margin-call trap before. So have a great many of his colleagues in what UBS and Campden call the “ultra high-net-worth, multigenerational family community.”

According to one of Moscow’s wisest bankers, the current contraction of global commodity prices, and the decline of mining and metal company share prices, are triggering bank margin calls to their Russian owners “every day from early morning to late at night.” There may be value in their assets, the source acknowledges, but there is no liquidity. That means a shortage of cash to service bank repayment demands – and no new loans.

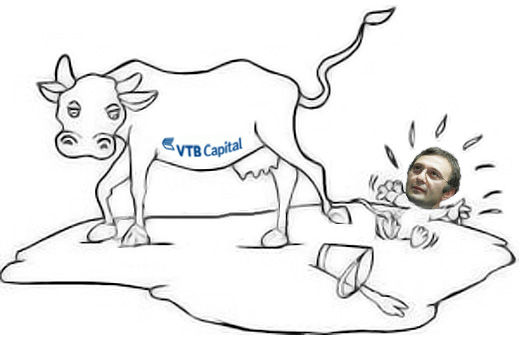

Last week it was reported in the Moscow business newspapers, on the grapevine, and in the market- maker reports to their clients that Mikhail Prokhorov was offering to sell his 38% stake in Polyus Gold to Kerimov (with a 40% stake). That’s a deal ostensibly worth about $4 billion, plus a premium for control of the company, less a discount for the reluctance of anyone else in the gold business to buy into the company. Kerimov, it was widely reported, could not raise a loan for the deal from the state-controlled VTB Bank. If true, that would be a sign of Kerimov’s deteriorating creditworthiness. He doesn’t speak for himself in response to questions; his Moscow holding, Nafta Moskva, announced it was not interested in buying Prokhorov’s stake.

Alfa Bank’s metals analyst Barry Ehrlich analysed the position this way: “We believe Prokhorov would be a seller under the right terms, given his interest in previous years in reducing his stake and his stated intention to exit the business in favor of a political career. Thus a deal looks possible. The fact that shareholders have at least discussed such a transaction (and approached banks for financing) may be one explanation for Polyus’ decision to hold off on its redomiciling in the UK. Once having done this, a takeover would require a mandatory minority offer. A transaction between shareholders would therefore open the door to redomiciling and FTSE listing. It would also remove a perceived overhang, as the market has long been aware of Prokhorov’s interest in selling at least part of his stake. On the negative side, investors are likely to feel less comfortable with a single oligarch shareholder structure.”

Another source, who has analysed Kerimov’s business position in London and Switzerland, believes the press leaks were from Prokhorov’s holding, Onexim, and were intended to push Kerimov into a corner, where he might be pressured into selling out of Polyus at a significantly lower price. Asking for protective anonymity, the source said: “I suspect the recent Polyus noises are actually Prokhorov drawing attention to the fact that Kerimov is broke so that he can make him sell as per the[eir shareholder] agreement. Both of them have starved the company of cash and hung on hoping that the other would drop out. Kerimov hoped Prokhorov would slip on a political banana skin and be forced to sell, as [Boris] Berezovsky was forced to sell to [Roman] Abramovich. Prokhorov was waiting for Kerimov to run out of cash.”

International bank sources believe there’s no comparison between the liquidity of Prokhorov and Kerimov – the former is “in good shape”, they agree. This doesn’t necessarily mean that Kerimov is in bad shape, so long as his Kremlin supporters will back his takeover of Polyus from Prokhorov, and authorize the means to do so. Last week’s leak of VTB’s loan denial may be false. But if true, it means that this time Kerimov’s liquidity is zero or negative.

That isn’t what Nafta Moskva has tried to convince the international business press after its September 12 statement denying it was interested in a deal with Prokhorov. On September 13 Kerimov’s holding said it was in talks to finance someone else to buy Prokhorov out. “Nafta is currently in preliminary discussions with one of the potential purchasers of Onexim’s shareholding … with a view to Nafta providing financial or other support (on terms to be agreed) to that purchaser.” This begged the question — what extra credit could Kerimov manage to muster which the third party couldn’t raise for himself? Is the third party facing more margin calls than Kerimov?

Again the speculation has been that Kerimov was trying to persuade the Kremlin to punish Prokhorov for his abortive presidential campaign last year, and make him lower his price to a figure Kerimov’s state banking credit could stretch to.

Prokhorov’s holding retaliated with a statement that implied it was sticking to its price, and had at least one, possibly two other buyers if Kerimov and his pals couldn’t scratch up the funds. According to the Prokhorov release, Onexim “confirms that it is in preliminary discussions, regarding a possible sale of some, or all, of its interest in Polyus Gold, with two potential purchasers in respect of an interest of less than 20 per cent. each in Polyus Gold. There is no certainty that Onexim will sell all, or any, of its interest in Polyus Gold.”

For years now, Prokhorov has been making similar sale claims, always implying that his target buyer was a major international goldminer. Not one of the big fish has bitten. So is there another Russian – not Kerimov but acceptable to him—who is capable of borrowing from the Kremlin, not only the Prokhorov exit price, but also the sum required to buy out the public minority shareholders? Is this transaction part of a bigger one in which Polyus Gold would be merged with Polymetal, owned by Kerimov, Alexander Nesis and others, in a state-financed formula comparable to the consolidation of the potash miners, Uralkali and Silvinit, in 2010-2011? There is no clarification from the Nesis camp, while spokesman for Nafta Moskva and Onexim said there have been no developments since their public releases on September 12-13.

Ehrlich of Alfa Bank reports the conflicting leaks as raising “the question – what is the missing ingredient that has prevented a transaction from moving forward? Most likely, it is state support and bank financing that would enable the transaction to occur. By making the deal public in this manner, the interested parties could be trying to solicit support for the transaction. In particular, about $4bn in cash will need to be provided to buy out the Onexim stake, which – as we have said in the past – would only be interested in a cash transaction.”

A week is a long time in Russian politics, and so far nothing has materialized in VTB financing. If you believe the 22 informants of the UBS-Campden report, the likelihood depends on someone bribing someone else. If you don’t, your hunch might be that President Vladimir Putin and his advisors have concluded that it isn’t in the nation’s economic interest to bankroll either Prokhorov or Kerimov.

Leave a Reply