By John Helmer, Moscow

Igor Zyuzin (lead image) is the first Russian oligarch to face prosecution for polluting the air around his factories. The announcement of criminal charges last week comes as Chelyabinsk regional and city officials escalate a war against lobbying by well-known names around President Vladimir Putin to save Mechel, Zyuzin’s coal and steel group, from the multibillion rouble cost of installing the clean-air controls required by Russian law.

On July 11, Interior Ministry Lieutenant-General Andrei Sergeyev announced that prosecution has commenced against Mechel on two counts of violation of Section 251 of the Russian Criminal Code. This covers air pollution in the Ural region city of Chelyabinsk. On conviction the charges can result in imprisonment for up to three years. Sergeyev promised that a month of investigation will now follow for prosecutors to identify the Mechel executives who will be charged.

The prosecution announcement follows years of citywide protests and public demands for Mechel to curb emissions of toxic chemicals from Mechel-Coke, a coke oven battery in the city, as well as Mechel Metallurgical Plant, the company’s steel-making complex nearby. Emission levels were fixed a year ago in permits issued to the company, but they have been consistently violated since then, Sergeyev said. He has repeated announcements of air quality monitoring carried out by the federal environmental control agency, Rospriradnadzor (RPN), as well as by local environment groups.

CLEAN-UP CAMPAIGN FOR AIR, CLEAN-OUT CAMPAIGN FOR ANTI-POLLUTION AGENCY

Above left: Gen. Sergeyev announces opening of Mechel prosecution in Chelyabinsk; top right: Yevgeny Botvinkin, prosecutor of the Khanty-Mansiysk Autonomous District, investigating corruption by regional RPN officials.

Below left: Murmansk RPN officials on trial last September for taking bribes; below right: Acting Head of RPN’s Central Federal District Konstantin Eliseev testifying last December in the extortion trial that followed a corruption investigation of his administration.

The air pollution findings, according to Chelyabinsk press reports, reveal dozens of occasions when the release of naphthalene into the atmosphere have exceeded last year’s authorized levels. As a consequence RPN ordered the cancellation of Mechel-Coke’s emission permits on June 15. This ought to have stopped production. The plant continues to operate, however.

Environment protection activists in the city are reluctant to say if they believe the prosecution will reach trial. If it does, the majority of Chelyabinsk residents expect scapegoats in the dock, while Zyuzin, the control shareholder of Mechel, escapes liability. So obvious is Zyuzin the target of the city’s anger, this week’s pervasive sewerage smell in Chelyabinsk is being described as Zyuzin’s doing, corporeally as well as corporately.

Oksana Agapova, public relations chief for the Ural region plants of Mechel, has reacted by saying coal processing and coke production produce a different kind of smell. “We consider it absurd,” the spokesman said, “to associate the appearance of the sharp smell of sewerage with Mechel enterprises. Coke production…cannot serve as the source of the smell of sewerage.”

At Moscow headquarters, Mechel has ignored the Chelyabinsk developments. Instead, the company announced it had received “an honorary diploma for its active participation in Russia’s Environment Protection Year. The award ceremony was held in Russian Presidential Administration building at a solemn function dedicated to the Ecologist Day and the International Environment Protection Day.”

When RPN revoked Mechel-Coke’s emission permits last month, the official government estimate was that one-fifth of all air pollution in Chelyabinsk comes from Mechel.

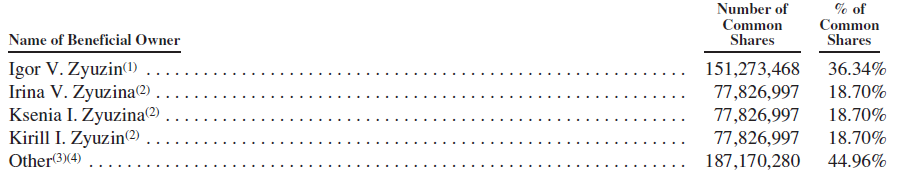

Zyuzin is Mechel’s control shareholder with 55% of the shares held by nominee entities in Cyprus — 36.34% in Zyuzin’s own name, and 18.7% held collectively by his wife and children. The share transfers within the family, reportedly made in 2014, did not breach Zyuzin’s undertakings to his creditors not to sell his shares.

MECHEL’S ANNUAL REPORT FOR 2016 – STATEMENT OF CURRENT SHAREHOLDERS

Source: http://www.mechel.com/doc/doc.asp?obj=122051 – page 222 Irina Zyuzin reportedly is not employed; Ksenia works in the chartering of freighters to carry Mechel’s coal exports, while Kirill works on coal mines. They hide their functions and their faces from the Russian press. For more, read this.

For the archive of Zyuzin’s business career and Mechel’s collapse into insolvency and semi-nationalization by the Russian state banks, read this.

It’s been five months since the last report; that was triggered by a severe winter pollution crisis in Chelyabinsk city caused by a temperature inversion and lack of wind. The report revealed the attempts Zyuzin was making to persuade (Editor warning: euphemism) the regional government headed by Governor Boris Zubovsky, and prevent orders for the installation of costly anti-pollution controls at his plants. For that story, read this. In the interval since then, the clean-up of corruption among regional inspectors and their supervisors at RPN has continued. That clean-up, regional activists acknowledge, has been the precondition for a clean-up of the air, and the new attack on Zyuzin’s business.

Left: Chelyabinsk region governor Boris Zubovsky; right: Chelyabinsk city residents respond to the air pollution threat last winter.

The anti-pollution, anti-corruption cleanup has gone unnoticed and unreported in the western media. They have made a hero of Zyuzin for being the first Russian corporation owner to list his shares on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) in 2004; and since then for purportedly standing up to the Kremlin. Reporters like Andrew Kramer (pictured below, left) of the New York Times and Courtney Weaver (right) of the Financial Times have led in misreporting the company’s affairs.

Kramer’s effort to depict Zyuzin as the victim of Kremlin corruption was so mistaken, his editors were obliged to issue a correction.

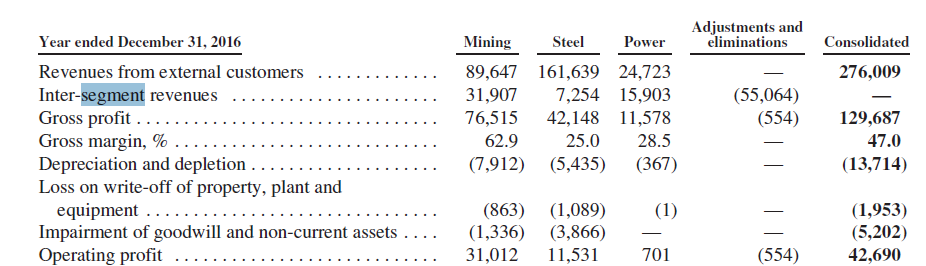

Kramer, Weaver and their colleagues have also tried to persuade the stock markets of New York and London to lift Mechel’s share price, but sharebuyers have proved resistant. In the past five years the market capitalization of Mechel has gone from $3.3 billion at peak in 2013 to a low of $225 million in December 2015. Driving the decline were Mechel’s debts and the collapse of the price of coal. Coal represents roughly one-third of Mechel’s revenues, while steel comprises almost 60%. However, the profit margin for coal and coke production is more than double that of steelmaking. Operating profit for coal was Rb31 billion last year; for steel, it was just Rb11.5 billion.

BALANCE-SHEET PERFORMANCE OF MECHEL’S COAL AND STEEL BUSINESSES, 2016

Source: http://www.mechel.com/doc/doc.asp?obj=122051

Mechel produces about 9 million tonnes of coal, and sells 6 million tonnes to export and other domestic customers; it is the second largest producer of coking coal in Russia, with a 19% share of the Russian market (Evraz has a 25% share). Pig-iron and steel production amount to 4.1 million tonnes and 2.8 million tonnes, respectively, most of it at the Chelyabinsk Metallurgical Plant.

The Mechel coke plant in Chelyabinsk is not the largest cog in this production chain, but it’s a vital one. The reason is that most of the plant’s coke is fed into the nearby steel works. Without the coke from Mechel-Coke, steel production would stop.

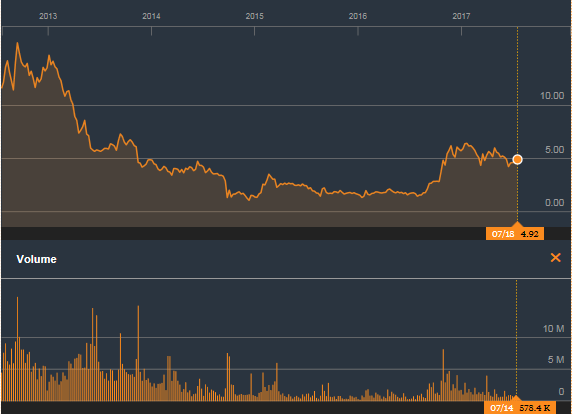

The recovery of the global price of coking coal from mid-2016 until January of this year lifted Mechel’s share price to a brief high. However, when the coal price dropped, so did the share price. Stockmarket interest, and hence the volume of share turnover, have dwindled significantly, as can be seen from this chart.

5-YEAR SHARE PRICE TRAJECTORY FOR MECHEL

Source: https://www.bloomberg.com/quote/MTL:US

But the glory days for coal, steel and Mechel are no more. The company’s peak share price was $101.42 on June 9, 2008, making a market capitalization then of more than $21 billion. Today’s share price of $4.92 gives a market cap of just over $1 billion.

Source: http://www.marketwatch.com/investing/stock/mtl

No Russian oligarch has been a bigger loser than Zyuzin. A Reuters reporter claims “he is known for his modest tastes. He owns only one house and drinks $12 bottles of New Zealand wine… He also hates debt, and in his early days avoided borrowing from state-controlled lenders.”

In fact, without the intervention of four state banks Mechel would be bankrupt and Zyuzin would have forfeited his shares. The principal bank lender to Mechel-Coke, and effective holder of security over the plant, is Gazprombank. In all, Mechel owes Gazprombank Rb 153.6 billion as of December 31, 2016. The total debt to VTB is Rb74.9 billion. Sberbank is owed Rb52.9 billion, and VEB, Rb11 billion.

For more than a year now President Putin has been involved in directing these banks, not only to agree on a debt rollover and rescue financing for Mechel, but also for preservation of Zyuzin himself. Lobbying with Putin in favour of Zyuzin a year ago, according to the Moscow press, were Igor Sechin of Rosneft; Vladimir Yakunin, then head of Russian Railways; Sergei Ivanov Junior, son of presidential chief of staff Sergei Ivanov; and Kirill Shamalov, Putin’s son-in-law. Ivanov Junior and Shamalov were directors of Gazprombank; Yakunin supervised contracts from Russian Railways for Mechel to supply steel rails.

Between then and now Putin forced Yakunin and Ivanov Senior out of office; Ivanov is now the federal overseer of environmental protection policy. Ivanov Junior was moved from Gazprombank to Alrosa, the diamond miner. Shamalov has stayed in his Gazprombank board seat. Zyuzin has kept his seat, too.

Zyuzin has been an invited guest at the past three Christmas dinners Putin has hosted for the oligarchs, but the Kremlin record reveals no direct one-on-one meeting between him and the president. Zyuzin also pays Alexander Shokhin (right) to mediate between him and the Kremlin. Shokhin is a Soviet-era diplomat who now runs the big business lobby, the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs (RUIE). In that role he is a regular at Kremlin meetings with businessmen. Zyuzin also pays Shokhin to serve as deputy chairman of the Mechel board. To head off the sanctions against Mechel in Chelyabinsk for the pollution offences, Shokhin has arranged for negotiations between the company and the regional authorities to include a go-between from RUIE.

has hosted for the oligarchs, but the Kremlin record reveals no direct one-on-one meeting between him and the president. Zyuzin also pays Alexander Shokhin (right) to mediate between him and the Kremlin. Shokhin is a Soviet-era diplomat who now runs the big business lobby, the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs (RUIE). In that role he is a regular at Kremlin meetings with businessmen. Zyuzin also pays Shokhin to serve as deputy chairman of the Mechel board. To head off the sanctions against Mechel in Chelyabinsk for the pollution offences, Shokhin has arranged for negotiations between the company and the regional authorities to include a go-between from RUIE.

Last month, at his nationally televised “Direct Line” question-and-answer session with the public, Putin took several questions from around the country on air and water pollution; they included one from a Chelyabinsk resident whose allotment garden had been condemned for being in a zone of heavy pollution. A Moscow region questioner complained at the toxic fumes from a landfill and garbage dump: “Many suffer from nausea and vomiting, all the time. It is unbearable.”

Putin replied equivocally: “This is a very sensitive and complicated issue. I know full well what you are talking about. I have seen this waste disposal site. As the reporter said, it has been there for 50 years. By the way, I see that you are standing by a building that was clearly built less than 50 years ago. Someone did decide to build housing near a waste disposal site that has been there for 50 years. So let’s not forget the people who took the decision to build residential buildings in this area. The dump has been there for 50 years. Nevertheless, we have what we have, and it is our duty to respond. Of course, we are aware of the problem. There is special urgency to deal with it in the Moscow Region, Tatarstan, Tula and a number of other regions.”

After a year of failed negotiations with Mechel, Chelyabinsk region and city officials are less equivocal. After RPN revoked Mechel-Coke’s emission permits and continued violating the required emission standards (pictured below), the company went to court on June 27, seeking a court order that RPN’s decision had been unlawful. The Chelyabinsk Arbitrazh Court has yet to set a hearing date. This is the basis Mechel lawyers believe entitles the plant to continue the pollution.

Source: https://www.chel.kp.ru/online/news/2795866/

So local prosecutors acting on General Sergeyev’s instruction have escalated the fight, adding a second criminal charge against the company.

Mechel has reacted by promising that “the Group’s Chelyabinsk facilities — Chelyabinsk Metallurgical Plant PAO and Mechel-Coke OOO — are implementing major ecological programs. In particular, Mechel-Coke has begun implementing a project of technical revamping of its benzene facility, isolating the coke gas final cooling water cycle in the by-product recovery plant #2. Implementing modern technology will enable the company to fully eliminate a large emission source.” The cost of the new measures is reported by the company to be Rb71 million.

Some regional government officials defend the company. According to Andrei Novoselov (pictured below, left), Deputy Minister of Ecology for Chelyabinsk, Mechel is operating legally, and is also volunteering to spend more on emission controls than other corporate polluters. The regional branch of Shokhin’s RUIE has announced that Mechel management is in favour of adjusting plant operations to emission control standards. Critics charge that Mechel has been paying a commercial laboratory to rig the test results, and that the air pollution is far worse when measured independently.

Vitaly Kuryatnikov (above, right), RPN regional chief for Chelyabinsk, has been accused in the local press of favouring Mechel and for breaching federal law and RPN regulations to allow the emission levels authorized for Mechel-Coke last year. He told a Chelyabinsk website last week: “We have had questions regarding the correctness of the previously issued permits. We regularly, systematically respond to the complaints of citizens on air quality. What measures should we take? Yes, we went about this in a non-standard way. We have checked the decisions. It should be understood that our area of responsibility in this matter is quite narrow. For example, we can check the measurements of the enterprise. The company does them to itself, and we only work with the data we have been provided. The state seeks a balance between administrative barriers, the rights of business, and the rights of citizens. But I think that this system, when the company itself designs its emission levels, and then measures its own compliance with the controls, was not justified.”

Should Mechel-Coke be shut down? Kuryatnikov says: “Yes, we can take this measure in the extreme case, but the issue isn’t so. I hope that regardless of the court decision, the company understands the need to reduce emissions and the measures that have already been required. What in fact is the most important thing/ We often hear demands to close the company. But what to do when there will be need for tax payments, jobs, social welfare requirements? There needs to be a balance.”

“But all the advantages that the city gives the company does not give it the right to pollute the environment. Our goal is environmental and economic balance. This situation should be approached soberly. We’re waiting to hear from Mechel-Coke the specifics on the program of environmental activities. Already announced is that one of the sources of the phenol, the cooling tower, will be eliminated. We are waiting for a more substantial program. Yes, it is unpleasant. It’s a situation of conflict. We were playing catch-up instead of solving the problem.”

Distrustful of both the company and RPN, the local environmental activist group My Planet says it wants Governor Dubrovsky to order public environmental accountability and public monitoring of air emissions around Mechel-Coke and Chelyabinsk Metallurgical. According to Vitaly Bezrukov (right), director of My Planet and a member of the advisory environmental council set up by the governor, “for nobody is it a secret that the enterprise [Mechel-Coke] is often one of the main sources of air pollution and as a result, participates in the formation of urban smog. Practically speaking, to stop this means the suspension of the plant’s activities…Repeatedly we have detected close to the enterprise an excess of phenol, naphthalene, hydrogen fluoride and sulphur dioxide. We plan to work to continue to exercise control by means of a permanent laboratory of research on the border of residential zones in areas of possible exposure to the company. I think that is one of the major steps in a solution, but still more is needed to be done. We encourage the residents of Chelyabinsk to contact My Planet. We invite you to join visits to the plant zones and to participate in the sampling of the air.”

says it wants Governor Dubrovsky to order public environmental accountability and public monitoring of air emissions around Mechel-Coke and Chelyabinsk Metallurgical. According to Vitaly Bezrukov (right), director of My Planet and a member of the advisory environmental council set up by the governor, “for nobody is it a secret that the enterprise [Mechel-Coke] is often one of the main sources of air pollution and as a result, participates in the formation of urban smog. Practically speaking, to stop this means the suspension of the plant’s activities…Repeatedly we have detected close to the enterprise an excess of phenol, naphthalene, hydrogen fluoride and sulphur dioxide. We plan to work to continue to exercise control by means of a permanent laboratory of research on the border of residential zones in areas of possible exposure to the company. I think that is one of the major steps in a solution, but still more is needed to be done. We encourage the residents of Chelyabinsk to contact My Planet. We invite you to join visits to the plant zones and to participate in the sampling of the air.”

What Zyuzin is saying in Moscow, and his men are telling the authorities in Chelyabinsk, is not revealed in the company’s report to the US Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC), the regulator for NYSE-listed companies. Mechel’s financial report for 2016, filed with the SEC at the end of April, makes no reference to the legal contingencies the company is facing in Chelyabinsk. As for environmental pollution liability, the report dismisses the claims as financially insignificant.

This is how Mechel reports the position to shareholders and the US Government: “In the course of the Group’s operations, the Group may be subject to environmental claims and legal proceedings. The quantification of environmental exposures requires an assessment of many factors, including changing laws and regulations, improvements in environmental technologies, the quality of information available related to specific sites, the assessment stage of each site investigation, preliminary findings and the length of time involved in remediation or settlement. Management does not believe that any pending environmental claims or proceedings will have a material adverse effect on its financial position and results of operations.”

Source: http://www.mechel.com/doc/doc.asp?obj=122051

“The Group estimated the total amount of capital investments to address environmental concerns at its various subsidiaries at RUB 647 million [$9 million] and RUB 644 million [$8.8 million] as of December 31,2016 and 2015, respectively. These amounts are not accrued in the consolidated financial statements until actual capital investments are made.”

“Possible liabilities, which were identified by management as those that can be subject to potential claims from environmental authorities are not accrued in the consolidated financial statements. The amount of such liabilities was not significant.”

Leave a Reply