By John Helmer, Moscow

Two men, Dmitrij Harder and Andrey Ryjenko, have been convicted in parallel proceedings in a US court and a UK court of arranging and receiving bribes in business transactions with the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD).

After several postponements over a year, Harder will be sentenced in US District Court in Philadelphia on July 18. On June 20, in the Central Criminal Court in London, Ryjenko was sent to prison for six years. A Crown prosecutor claimed: “Andrey Ryjenko repeatedly abused his position of power within a publicly-funded bank by accepting corrupt payments.” She added that without the US prosecution of Harder, his guilty plea, and agreement to cooperate in testifying against Ryjenko, there would have been no case. “This conviction was made possible through effective cross-border partnerships between a number of jurisdictions, including the United States.”

The UK lawyers who represented Ryjenko, barrister Jeffrey Chapman QC and solicitor Jessica Skinns of Bindmans, refuse to answer questions about the case, and will not release the evidence they presented in court. But lawyers who have reviewed the case in the UK and US say there was a loophole in the law on which the prosecution of both men has been based. US lawyers admit they didn’t know of it when they were arguing their case in Philadelphia a year ago that the charges against Harder should be dropped.

Court testimony in London and statements from the EBRD also reveal there has been a cover-up of intelligence agency involvement in the two cases, and political intervention in the longstanding conflict between the US government and other governments on the EBRD board and the bank management over how much, or how little money the bank should lend to and invest in Russia.

The records of the EBRD show that the two Russian oil and gas companies, which were the payors of the purported bribes, were absolved of any wrongdoing. They continued their business with the bank, which earned at least $40 million in investment profit and millions of dollars more in income from interest and management fees from the transactions.

After six years of arguing that his business with the EBRD was normal and legal according to EBRD policy, in April 2016 Harder (pictured below, left) pleaded guilty to the offences charged against him under the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA).

Ryjenko (above, right) pleaded not guilty. He has maintained for the seven years of litigation since he was first charged in February 2010 that what he had done was lawful and customary practice at the EBRD. Ryjenko also testified that the prosecution against him was influenced by efforts MI5, the UK intelligence agency, had made to recruit him to spy against the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR). The evidence in court was that when Ryjenko rebuffed MI5, MI5 told EBRD to file a corruption claim with the City of London police. For more details, read this.

Nicholas Cooke QC (below, left) , the British judge who sentenced Ryjenko to prison, acknowledged in court that without Harder’s plea bargain and testimony, the prosecution of Ryjenko would have been impossible. Federal US Judge Paul Diamond (right) has rejected all Harder’s motions to dismiss the charges, triggering the plea bargain between Harder and the US government requiring him to cooperate in the Ryjenko prosecution.

There was a loophole in the EBRD charter, and in the US presidential decree ratifying the charter, which ought to have stopped both prosecutions — except that the lawyers for Ryjenko and Harder didn’t present it to the judges for a ruling. Sources close to the case claim the lawyers didn’t know.

There is also a suspicion, the sources concede, that US and UK Government officials involved in the case were only interested in Russian government targets like the SVR; and that once the EBRD announced in 2014 that it was halting all new business with Russia, they had achieved the objective which the US Treasury has been pursuing since the very beginning of the EBRD in 1991.

For the record of the fight between the US and the European governments to stop capital flows to Russia, read Adam Bronstone’s history. This record reveals that the Bush Administration wanted to keep the USSR out of the EBRD at the start, and then curtail lending to Boris Yeltsin’s Russia. There was also bitter, personal contention between US Treasury Secretary Nicholas Brady and French President Francois Mitterrand and his nominee as the EBRD’s first chief executive, Jacques Attali — until Attali was forced out of office in 1993.

Above: the EBRD’s official photo archive for the inaugural ceremonies on April 15, 1991, shows the EBRD president, Jacques Attali, (left), and to his right, British Prime Minister John Major; Irish President Mary Robinson; and French President Francois Mitterrand. Below in the front row, from left to right, Mitterrand, Major, Attali, and despite his minuscule shardeholding in the bank, Yitzhak Shamir of Israel. US Treasury secretary Nicholas Brady spoke at the inaugural meetings, but was absent from the official photographs. He and the Europeans had repeatedly clashed over lending policy towards the USSR, then Russia. Brady and David Mulford, his chief negotiator at the EBRD, regarded the Russians as enemies from the beginning, and aimed to restrict EBRD’s lending to Moscow as much as possible.

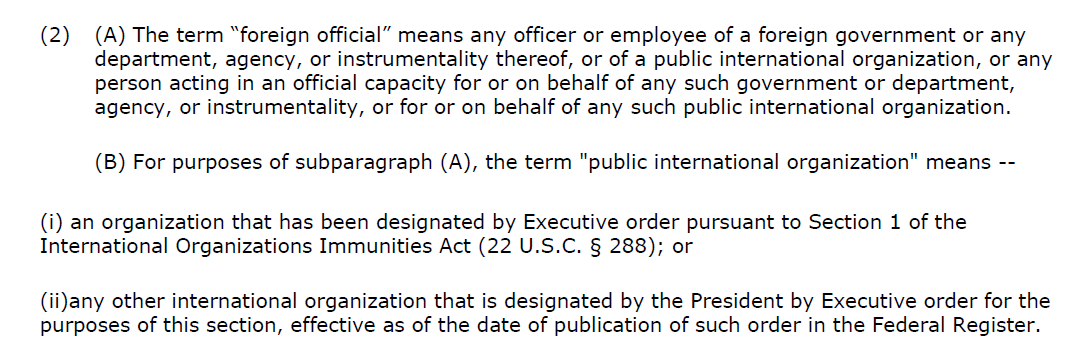

In the Harder prosecution papers filed at the federal district court in Philadelphia, US Department of Justice officials and the Philadelphia District Attorney say their prosecution of Harder was based on a presidential decree of 1991. This decree, they claim, legally identified Ryjenko as a “foreign official”, according to the FCPA statute, and thus made Harder’s payments to Ryjenko’s sister, Tatjana Sanderson, a criminal bribe.

Judges and lawyers on both sides of the Atlantic admit this was the lynchpin of both cases. If Ryjenko wasn’t a “foreign official”, under FCPA, then Harder’s payments were as lawful on the US side as Ryjenko said it was lawful to receive them on the UK side. Without this, the Americans didn’t have a corruption case against Harder. Without his testimony against Ryjenko, the British had an unlikely, if not impossible case to prosecute against Ryjenko.

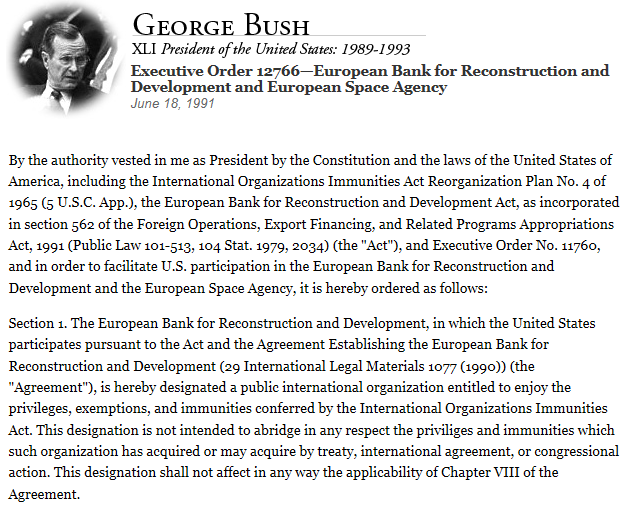

“On or about June 18, 1991,” says the US indictment of Harder, dated January 6, 2016, the President of the United States signed Executive Order 12766 designating the EBRD as a ‘public international organization.’ The EBRD was thus a ‘public international organization’, as that term is defined in the FCPA, Title 15, United States Code, Section 78dd-2(h)(2).”

Read the indictment here. And here is the section of the FCPA to which it refers.

THE US DEFINES “FOREIGN OFFICIAL” FOR PROSECUTING BRIBERY

But the executive order carries an important qualifier which the Justice Department didn’t mention. Read carefully.

THE PRESIDENTIAL DECREE ALLOWING EBRD’S IMMUNITY FROM US LAW

The lynchpin turns out to have a loophole. The EBRD designation, President George Bush decreed, was not lawful if it “abridged in any respect” the “priviliges [sic] and immunities” which the EBRD and its staff had acquired by the agreement creating the organization. Central among those privileges and immunities for a dual Russian-British national like Ryjenko were Articles 32 and 33. They remove the bank, staff bankers like Ryjenko, and business transactions they conduct with consultants like Harder, beyond the reach of US statutes like FCPA.

According to the EBRD charter, “the Bank, its President, Vice‑President(s), officers and staff shall in their decisions take into account only considerations relevant to the Bank’s purpose, functions and operations, as set out in this Agreement. Such considerations shall be weighed impartially in order to achieve and carry out the purpose and functions of the Bank… The President, Vice‑President(s), officers and staff of the Bank, in the discharge of their offices, shall owe their duty entirely to the Bank and to no other authority. Each member of the Bank shall respect the international character of this duty and shall refrain from all attempts to influence any of them in the discharge of their duties.”

Ryjenko, a national of Russia and the UK, has insisted that what he had done was lawful, according to the EBRD charter and the EBRD rules. He also testified that facilitation or success fees, like those Harder received from the two Russian companies borrowing from the bank, were lawful and normal EBRD practice. Ryjenko said he didn’t believe he was subject to US law – and he wasn’t.

Across the Atlantic, Harder, a Russian and German national with permanent US residency, was saying the same thing. At least that’s what he said at the beginning, when by secret arrangement between the UK and US authorities, Harder was detained after landing at Kennedy airport in New York on February 26, 2010. Harder had arrived from a business trip to London, Moscow, and Baku. Agents from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and other US agencies questioned him with a script dictated by the FBI and Justice Department in Washington. They in turn were acting on communications from the UK authorities in London.

Harder wasn’t arrested; he could have refused to talk and walked out of the airport to go home. Instead, Harder agreed to answer the agents’ questions for two hours. Here is a partial record of what happened and what was said.

The US interview record reveals that Harder “named the EBRD employees with whom he was working, including Ryjenko and several others…He was asked about Sanderson, whom Defendant [Harder] described as one of Chestnut’s ‘producing agents’. Defendant said that he had wire transferred some $1 million to Sanderson to set up a mortgage brokering company. In response to their questions, Defendant told the Agents that he did not know that Ryjenko and Sanderson had been arrested or that Sanderson was Ryjenko’s sister.”

Harder may have been lying; he may have been telling only part of the truth. The record was admitted into evidence against him six years later. The “several” other EBRD staff Harder named have not been accused by the UK authorities of any unlawful conduct for “working” with Harder. Although Sanderson was charged with Ryjenko, UK prosecutors agreed with Ryjenko and Sanderson that she will not face trial.

In Harder’s case, his lawyers argued in a motion for dismissal that the EBRD should not have been designated as a public international organization at all on constitutional grounds. Judge Diamond rejected that claim. “The President,” he ruled, “acted permissibly within these boundaries when designating EBRD a public international organization. As the applicable Executive Order confirms, the President invoked his authority under the IOIA and acted consistent with it when recognizing EBRD as a public international organization….Because EBRD is constitutionally included in the FCPA.”

Lawyers involved confirm they did not raise in court the special exemption for the EBRD’s “privileges and immunities” contained in the Bush executive order. The judge also ignored the wording of the order when he ruled that in Harder’s case “the FCPA thus proscribes unlawful conduct in connection with a public international organization — itself an association of foreign governments.” Diamond failed to examine the EBRD’s charter, and the immunity from FCPA it extended to staff men like Ryjenko, so his ruling against Harder was inevitable: “Defendant is not entitled to dismissal of the substantive FCPA Counts,” Diamond decided.

According to Diamond, the FCPA law under which Harder has been prosecuted “makes it a crime to bribe a third party if the payor knows that foreign official will ultimately receive the payment and will thus be induced to act unlawfully.” But was Ryjenko acting unlawfully under the EBRD charter? And was Harder acting unlawfully if Ryjenko was not? Diamond avoided answering these difficult questions because the lawyers in his courtroom didn’t ask them. “Plainly, an ordinary person—and especially a sophisticated businessman like Defendant [Harder] —would understand,” said Diamond, “that the EBRD is a public international organization both literally and legally, and that bribing an employee of such an organization could well be criminal.”

At EBRD headquarters in London ordinary persons don’t count. The charter agreement, the organization’s rules, and the code of conduct for staff do. Did Ryjenko’s lawyers, Chapman the barrister (below, left) and Skinns the solicitor (right), argue in defence of Ryjenko that the application of the US statute and Executive Order 12766 were mistaken; that Harder’s testimony had been obtained unlawfully and should not be admitted in the London court? Did they warn Judge Cooke that EBRD’s charter gave Ryjenko, Harder and Sanderson immunity from US prosecution under FCPA?

They refuse to say. Chapman says he can’t answer questions unless instructed by his solicitors. Skinns said by email: “I am not in a position to comment on Mr Ryjenko’s case at the moment. Nor do we have a transcript of the evidence.” Her claim about the evidence transcript is unlikely to be true.

The EBRD is also stonewalling. As reported in a public bond prospectus issued in January 2011 by Vostok Energy, one of payors to Harder, sometime between 2009 and 2011 the EBRD “had commenced an internal investigation in relation to Chestnut [Harder’s consulting firm] and, as part of this investigation, EBRD asked the Issuer to engage an independent consultant to review and report on the Issuer’s engagement of Chestnut. The EBRD approved the engagement of Ashurst LLP for this purpose.” The Ashurst lawyers cleared Vostok Energy of any culpability in its dealings with Harder. The EBRD told Vostok Energy “that, unless new information comes to light, it does not intend to investigate further the matter insofar as it relates to the Issuer.”

That sounds like the bank, plus the Ashurst law firm, judged that payment of a facilitation or success fee to Harder for his part in the EBRD loan and investment deal with Vostok Energy was normal practice and lawful.

Ashurst describes its New York and Washington DC offices as “focus[ing] on our core businesses which include banking, energy, resources and infrastructure, structured products, tax, financial regulatory, and corporate and capital markets.” No source familiar with the Harder and Ryjenko cases doubts that Ashurst lawyers must have known what the terms of the FCPA were. There is also no doubt that Ashurst must have advised EBRD there was no liability between the bank and Vostok Energy; this can be concluded because Ashurst was the designated “legal adviser” for the Vostok Energy prospectus. MI5, on the other hand, was interested in Ryjenko. At the time, that was all EBRD, according to the Vostok prospectus, was interested in too.

The EBRD now says “we are committed to promoting integrity, good corporate governance and high ethical standards in all business operations.” The bank’s current code of conduct for staff was issued in 2012. This sets out guidelines for conflict of interest which in retrospect should have covered Ryjenko’s sister’s business with Harder. But was that clear in the EBRD code of conduct between 2007 and 2009, when the transactions Ryjenko has been convicted of, and Harder pleaded guilty to, took place?

Success fees of the kind Harder received — the EBRD calls them “facilitation payments” — are also identified in guidelines published by the bank in 2016 as “Prohibited Practices Guidelines for EBRD Operations”. “The EBRD does not condone facilitation payments regardless of whether they are criminalised or not. Such payments, which are illegal in most countries, are dealt with in accordance with relevant law and international conventions.” Was “not condone” clearly EBRD’s policy between 2007 and 2009? To date, it has not been possible to answer these questions from EBRD’s publicly accessible archive.

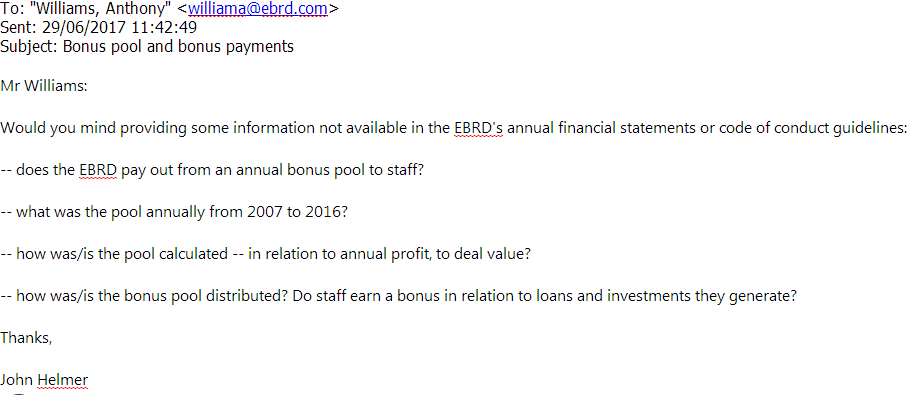

The bank’s financial statements and annual reports do not reveal what policy and practice the bank has followed in paying success fees, or bonuses to its own staff, when loans and investment deals have been finalized with clients. According to observers of the Ryjenko trial at the Old Bailey, and Ryjenko’s evidence, commissions which are now treated as illegal were not regarded as such when Harder, Ryjenko and Sanderson did their business together.

EBRD’s spokesman, Anthony Williams, was asked to explain:

Williams and his bank refuse to answer.

Leave a Reply