By John Helmer, Moscow

@bears_with

Philip Short, a journalist from the BBC, has published a new book which claims to be a biography of Vladimir Putin. It isn’t.

What it is instead is a biography of one hundred and twenty-three westerners — what they claim to know about Russia’s leader and what for commercial motive, reason of state, or vanity they have told Short in interviews he conducted for his book. They include spies he names without their cover – John Scarlett, Richard Dearlove, Richard Bridge, Kate Horner, Martin Nicholson, and Pablo Miller from the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6); Hans-Georg Wieck and August Hanning of the Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND); Jean-Francois Clair, Raymond Nart, and Yves Bonnet of the Direction de la Surveillance du Territoire (DST); Seppo Tiitinen of the Finnish Security Intelligence Service (SUPO); Mark Kelton, Michael Morell, Peter Clement, Michael Sulick, Michael Morgan, Paul Kolbe, and William Green of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA); Juri Pihl, head of the Estonian Internal Security Service, and Eerik-Niiles Kross, chief of Estonian intelligence; and several dozen other ambassadors, consuls, advisers, headquarters staff, journalists, and think-tankers.

Not one of the spies was operational in Moscow for the past twenty-one years of Putin’s terms in office.

There is a flash of originality in this book. Not a single source on which Catherine Belton’s book on Putin relies has been interviewed by Short; in his references to Belton’s claims Short reports they “appear to be untrue”. He reaches the same conclusion about two other books about Putin, Karen Dawisha’s and Masha Gessen’s. “Neither book pretends to be a balanced account”, Short says. Dawisha’s book “is marred by numerous errors of fact”. “All three”, Short warns, “set out the case for the prosecution, and like all prosecutors, the authors select their evidence accordingly.”

“Readers must decide for themselves,” Short concludes his book, “what is plausible, what sounds false, what rings true and what does not.” This is how Short ends on page 679 with what most biographers begin on page 1.

Left, the book published in the UK and US this month.

Centre: Philip Short who was a BBC correspondent between 1973 and 1998. Right: for more on the mind of Putin the mnemonist, and the Soviet cognitive psychology classic which first identified how such prodigious memory works, read this.

Instead, at Short’s beginning he trots out the old cliché of Russian politics written by westerners – that’s the canine definition of Kremlinology attributed to Winston Churchill as watching “a bulldog fight under a rug – an outsider only hears the growling, and when he sees the bones fly out from beneath it is obvious who won”. Short admits this isn’t new. “[It’s been] true of Russian governance since the sixteenth century. The Kremlin does not yield its details easily. The broad outline may be clear but the devil is in the details and the details matter. If enough details change, the overall picture changes too.”

Between this opening fatuity and his concluding one, Short has compiled a long list of fatuities about Putin. Since the espionage agents who provided Short with his interviews didn’t work in Russia after Putin took power, the fatuities are hearsay by at least six degrees of separation.

On the positive side of Short’s character ledger, there are Putin’s self-discipline, loyalty to friends, shyness, loneliness, indifference to money, love of sport, and his “excellent memory”, “brilliant memory”, and “unusually retentive memory”. On the negative side of the ledger, there are his secretiveness, unpunctuality, inconsiderateness towards women, calculation, repressed emotions, sensitivity to his short stature, taste for luxury, and “obsessive self-control”.

Their combination in Putin’s character was an immaculate conception, according to Short. “Even as a child,” he recounts, “Volodya Putin had concealed his hand; as a young man, he did not vouchsafe information unless there was good reason. Putin’s time with the special services influenced his thinking and equipped him with new tools with which to view the world. But it did so by accretion. Putin was already Putin before he joined the KGB.”

For his evidence Short interviewed one-third as many Russians as westerners. The majority of the Russians are or were journalists; none of the remainder is from a Kremlin, Russian government, intelligence or military position during Putin’s presidential terms except for Mikhail Kasyanov, prime minister from 2001 to 2004, and Andrei Illarionov, an economic advisor between 2001 and 2005. The others are from the Yeltsin administration; they were, still are uniformly Yeltsin supporters hostile to Putin — except for Mikhail Delyagin and Yury Boldyrev.

With sources like these, it is little wonder the violent constitutional battle between Boris Yeltsin and the Russian parliament of October 1993 is described by Short as being fought on the anti-Yeltsin side by a “hard core of 150 deputies…protected by an armed militia of Cossacks, Chechens, Afghan veterans and far-right nationalist thugs.”

Not a single Russian business figure or oligarch has been included in Short’s Russian interview list – with a sole exception. He interviewed three members from the aluminium oligarch Oleg Deripaska’s payroll. Short’s version of Putin’s record on the domestic economy and the oligarch businesses follows Deripaska on metals; Mikhail Khodorkovsky on oil, Yukos and Rosneft; William Browder on gas and Gazprom; Illarionov on the financial collapse of 1998.

The snippets Short composes of other Russian characters in the story are also fatuities, but he leaves no doubt which ones he intends his readers not to take a liking to, and vice versa. For instance, Yevgeny Primakov, head of the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), foreign and prime minister in the 1990s – until removed on US orders — appears 51 times; he is introduced as “a bespectacled academic with jowls like a basset hound…a tough, pragmatic conservative”; Khodorkovsky appears 82 times as “short and solidly built, ten years younger than Putin, he had close-cropped black hair beginning to grey and, behind rimless spectacles, a gaze whose intensity gave him the appearance of a youthful nineteenth-century anarchist.” Alexei Navalny appears 99 times in Short’s book as “35 years old, a tall, slim man with Nordic good looks – dark hair and piercing blue eyes, who…had a knack of skewering the elite with pungent phrases that lodged in people’s minds and was refreshingly direct.” The numbers signify Short’s measurement of their impact on Putin’s history over the past thirty years. A westerners’ measurement, not a Russian one.

Oddly, Short doesn’t mention that both Primakov (Finkelstein) and Khodorkovsky were Jewish. He does make a point of claiming, inaccurately,

that Jews were barred from the KGB. He also makes another point of emphasizing the Jewish origin of Galina Starovoitova (right), the Soviet

dissident and liberal politician assassinated in November 1998, when Putin was head of the Federal Security Service (FSB). Short claims the killing was part of “a wave of anti-Semitism, whipped up by ultra-nationalist members of [Vladimir] Zhirinovsky’s party in the Duma.” Zhirinovsky’s Jewishness (Eidelshtein) is omitted from this story.

So convinced of the stories Short retells of Primakov’s malign influence it didn’t occur to him to check with Primakov, who was alive when Short began his interviews; or his presidential campaign partner Moscow mayor Yury Luzhkov, alive until 2019; or any one of their associates and advisers. No one on the Russian left was interviewed directly or indirectly at all. Dmitry Rogozin — Putin’s appointee as NATO ambassador, deputy prime minister in charge of defence, and head of Roscosmos — was disposed of by Short as “a solidly built right-wing firebrand whose rhetoric attracted malcontents both from the far left and from extreme far-right groups.” The meaning of left and right in Short’s vocabulary is unexplained, taken for granted to mean anti-western. Sergei Glazyev, the leader of the left economic line in Putin’s Kremlin is not mentioned at all. By contrast, Alexei Kudrin, on the right, is reported 33 times; Anatoly Chubais, 57 times. Short reports interviewing his brother Igor Chubais, but not what he said.

Short repeats what he has read of the stories already published of Putin’s time in Dresden, then in Mayor Anatoly Sobchak’s administration in St. Petersburg. His version of Putin’s rise in the Kremlin follows what he was told in his interviews and by the published version of Konstantin Yumashev, Yeltsin’s bagman, son-in-law, ghost writer. Nothing new.

Nor is Short’s discovery of what he thinks is new evidence. For Short’s conclusion that Putin ordered the polonium poisoning in London in November 2006 of Alexander Litvinenko he refers to a CIA double agent reporting from inside the Kremlin and then spirited out of the country to the US. Short repeats the New York Times for the existence of this agent, but because the newspaper made no mention of the agent’s knowledge of the Litvinenko case, Short claims “others with knowledge of the evidence given in the Litvinenko Inquiry have confirmed that the crucial material indicating Putin’s involvement came from ‘HUMINT’ [Human Intelligence] provided by the United States. The only US intelligence asset in Moscow capable of providing information at that level was the source referred to in the Times account.”

That’s Short’s guess after he has hidden the British sources pointing him away from the MI6 role in the operation before Litvinenko’s fatal tea party. The anonymous New York Times version of the Kremlin source, like the MI6 source who gave me his version of what happened, does not corroborate Short’s conclusion that Putin had instructed the FSB chief, Nikolai Patrushev, to assassinate Litvinenko. “Raw intelligence is not proof”, Short concedes, “but” – note the qualifier removing doubt – “it was prima facie evidence that the decision had been taken by Putin himself.”

This is fabrication by Short once it is understood that MI6, CIA, SVR and other agencies involved in tracking the polonium from Moscow to London interpreted what was going on as an operation aimed at Boris Berezovsky, not Litvinenko. Short’s spies didn’t tell him. He doesn’t know.

Short’s version of the Novichok poisoning case involving Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia has been reproduced directly from the British government’s published stories. “In March 2018 the GRU attempted to assassinate a former double agent, Sergei Skripal, who had been freed as part of a spy exchange and was living in the sleepy cathedral city of Salisbury, in the South of England. The Russian operatives had smeared Novichok, a prohibited chemical warfare agent on the door handle of Skripal’s house. He and his daughter recovered but another person died.”

From his study window in the sleepy village of La Garde Freinet, in the South of France, that’s what Short thought he could see. But he didn’t investigate. Instead, he has concealed that “the sleepy cathedral city of Salisbury” is in fact the centre of British, as well as US chemical warfare manufacture and testing at the Porton Down establishment, and on Salisbury Plain the headquarters of the main artillery, infantry, intelligence and chemical warfare units of the British Army. Short has even muddled the facts of the case, tying the death of Dawn Sturgess to the poisoned door handle. This isn’t simple error on Short’s part – it’s plain BBC standard propaganda. Short claims Putin is guilty again. “In Skripal’s case, unlike that of Litvinenko, there was nothing to suggest that Putin had ordered the attack or even that he approved it…Afterwards, however, he covered up for those responsible.”

Short’s idea of nothing to suggest is plenty. In the case of the death of Sergei Magnitsky, Short cribs Browder’s account without testing the court evidence that Browder (right) is a liar. In his history of the Maidan demonstrations in Kiev in January 2014 and the putsch that followed on February 21, Short repeats claims without an official or intelligence source; he is duplicating the New York Times. Later in the Ukrainian story he reruns, Stepan Bandera “had been rehabilitated…to pretend that the Ukrainian government was run by Nazis was absurd. [Vladimir] Zelensky was a Russian-speaking Jew — hardly the man to lead what Putin termed dismissively ‘a junta of neo-Nazis and drug addicts. For Russians, particularly of the older generation, Putin’s allegations resonated. In the West, they appeared malign and surrwal.”

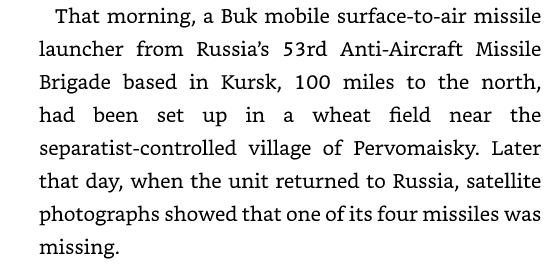

Short has abandoned the truth test. The version he proclaimed at his conclusion — “readers must decide for themselves what is plausible, what sounds false, what rings true and what does not” — he makes impossible because he conceals the evidence, the proof of what could not have happened; in their place he substitutes fabrications. For example, the downing of Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17 over eastern Ukraine on July 17, 2014, Short reports this way:

This is false. Short footnotes his claims from the NATO propaganda unit known as Bellingcat, but he not only fails to check that source of evidence, he is totally ignorant of the contrary evidence presented during the Dutch court proceedings which began on March 9, 2020. Short doesn’t know there are no satellite photographs of the aircraft incident; that this has been confirmed by the Dutch investigators and judges; and corroborated by Dutch and American intelligence officers whom Short’s interviewees concealed. The photographs Short mentions were fabricated in Kiev by the Ukrainian Security Service (SBU).

For more on the fabrication of the US satellite allegations, click to read.

From MI6, Bellingcat and the SBU, it is a hop, step and a jump for Short to Navalny’s August 2020 collapse in Tomsk. Short repeats the German and other government announcements that “he had been poisoned with a cholinesterase inhibitor, subsequently identified as a nerve agent of the Novichok group, similar to that used against Sergei Skripal in Salisbury.” This account, Short reveals in his footnotes, “is drawn from a Bellingcat investigation”. Short investigated nothing else before concluding that Putin was responsible for ordering Navalny’s assassination.

“The issue, however, was not whether Putin was lying. He was. The question was whether he had himself ordered Navalny killed, or whether…the final decision had been taken by siloviki in his inner circle who assumed that he would be only too glad to see his long-time adversary removed…Yet there are good grounds for thinking that Putin himself took the decision.”

This is Short’s decision — and it’s contradicted by the conclusion he buries at the very end of his book in footnote number 159 on page 757. An incident he reports as striking an experienced CIA agent he interviewed as “inconceivable…was exactly what Putin had done.” Short then pronounces the rule of biographies of Putin and histories of Russia: “the recurrent weakness of Western intelligence services’ and journalists’ reporting on Russian events which do not fit an expected pattern are too readily dismissed as implausible. Anomalies can be revealed and usually merit closer examination.”

Ditto Short.

Leave a Reply