By John Helmer, Moscow

In the jungle there’s not much call for the subtle touch. So it’s not clear whether Mikhail Fridman’s announcements this week are intended as a dagger or as a club.

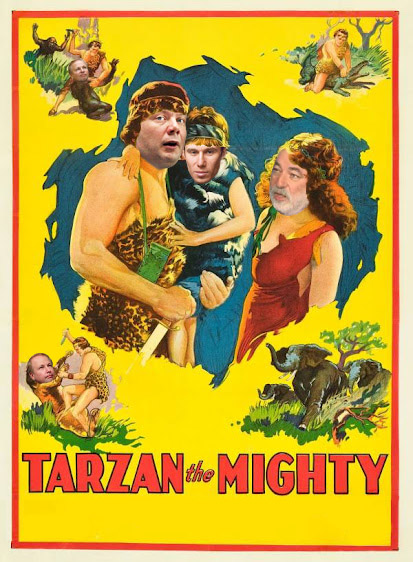

By resigning his chairmanship of the management board of TNK-BP, and vacating the chief executive’s role, Fridman (image centre left) hasn’t left the governing board of directors of TNK-BP, the joint venture between BP and Fridman and his partners, German Khan (image centre), Len Blavatnik, and Victor Vekselberg (centre right); the latter combine in a group named AAR after each of the initials of their holdings – Alfa, Access, Renova.

But the resignation reinforces the move a week ago by Fridman and AAR to cancel the scheduled May 25 board meeting on the ground that the 11-member body lacks a quorum. The shareholder agreement between BP and AAR for governing TNK-BP provides for the control shareholders to have four representatives each on the board, and three non-affiliated directors on which the two control shareholders must agree. Since December, they have agreed on two. But the missing one deprives the board of its quorum.

In an interview published in Kommersant today, Fridman declares that he is opposed to the board agreeing to pay this year’s dividends from TNK-BP’s profit to BP, or to himself and to the AAR consortium.

When we last saw BP’s chief executive, Bob Dudley (upper, lower left), he was hanging on for dear life, arm raised in an appeal for mercy, and money. Before Tarzan brings down the knife this time, the gorilla’s hand appears to be up for payment of his half-share of TNK-BP’s first-quarter dividend of $860 million. No board quorum, no dividend payout — if BP no speak Tarzan pidgin.

The shareholder agreement between BP and AAR, establishing TNK-BP, provides that 40% of the profits should be paid in equal shares to the two of them. So BP is expecting $430 million. The balance would go in proportion to their stakes in AAR — Fridman would take 25%, Khan and Vekselberg 12.5% apiece. So right now, in knifing Dudley’s share Fridman is cutting himself.

TNK-BP’s financial reports indicate that for last year 2011, it declared dividends paid to “Group shareholders” of $7.49 billion, and another $369 million paid to “noncontrolling interest shareholders”. The former group, comprising BP and AAR, helped themselves to 111% more than they had done in 2010. The latter, a free-floating 5% in a subsidiary listed in the Moscow stock market, got just 9% more.

The latest TNK-BP financial report for the quarter ended March 31, 2012, indicates that $1.38 billion was paid out in dividends in that time period. BP confirms in its most recent quarterly report that it has now received from TNK-BP its entitlement to precisely half — $690 million.

BP and Russian sources also explain that the balance-sheets are recording dividend payouts and receipts with a lag in time between the periods for which the dividends were declared, and the periods in which the money was transferred to the stakeholders. For the full year of 2011, for example, BP reports receipts of zero in the first quarter; $1.6 billion in the second; $425 million in the third; and $1.7 billion in the fourth. Total receipts, $3.74 billion.

Until this month, BP was receiving its cash more or less on time. A Reuters report posted with apparent endorsement on the AAR website on May 22 implies there will now be an indefinite delay in payment of BP’s share of what TNK-BP earns this year. Depending on how oil prices move and what happens to TNK-BP’s earnings, the holdup can be calculated to be worth between $3 billion and $4 billion to BP.

A report today by Troika Dialog analyst Alexei Bulgakov calculates the cut for each of the TNK-BP shareholders this way. “Historically, AAR members, having their own leveraged investment holdings, have been at least as interested in high dividend payouts as BP since the Gulf of Mexico disaster. The largest member of the consortium – Alfa Group – is likely better off now than it was four years ago (it received payment for its share in MegaFon) and can probably survive for a while without receiving cash from the venture. However, the leverage constraints of other AAR partners (for example, Viktor Vekselberg’s Renova Holding) may be much stricter.”

“Meanwhile, BP Plc badly needs cash from its Russian venture – it pays quarterly dividends that are almost fully funded with cash from TNK-BP, so any interruption in dividends from the JV would force it to borrow, which may be cumbersome, though not entirely difficult for an A-rated company.”

In his extended interview with Kommersant, published today, Fridman says: “We actually need the money, too. I would say so, the overall situation in the business now is not the most favorable in order to pay big dividends. Oil prices are unstable; there are threats of serious crisis. In addition, in the absence of a functioning board of directors, the company cannot get a decision to borrow in the financial markets.”

“BP needs more high dividends because they have big problems with liquidity because of the need to pay compensation for the oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, and in general [because of their] disappointing financial and operational results. Therefore, BP insists on payment of dividends; it has threatened to force the company to do this through international arbitration. At the same time, the management of TNK-BP believes that it would be correct to leave the funds, which were dedicated for the dividend, in the company”.

What Fridman appears to be saying is that if BP wants its cash for now, it must agree to Fridman’s terms for later. “BP is a minority shareholder, and is gradually emerging from the capital of TNK-BP. This process is not an instant one. It can be extended in time. We are looking for a possibility of reducing the packet if a certain portion [of the TNK-BP stake] will be converted into shares of BP. If we go down this path, it may take five to seven years.”

At the moment, according to BP’s reports, the two largest of the shareholders on record are BlackRock with 5.93% and Legal and General Group with 4.18%. At the current market capitalizations of BP and TNK-BP — $117 billion and $39 billion respectively – a half-share of TNK-BP, worth say $20 billion in money terms, might be swapped for 17% of BP’s share issue. Even allowing for an elephant-sized discount, if Fridman and AAR are offering to sell out, they are also demanding the single largest bloc of BP shares, making them collectively the de facto control shareholder. That’s curtains for Dudley, and quite a few others.

One of the wisest investment bankers in Moscow regards the Fridman offer, and the inevitable BP resistance, as a recipe for protracted conflict. “I have no idea how this plays out. AAR will always sell if the price is right but the buyer is unlikely to be BP. My best guess is that this dysfunctional marriage will continue with AAR steadily improving its position through guerrilla war. For what it’s worth, my view remains that AAR has the better argument on how the firm should develop.”

Another way of interpreting Fridman’s remarks is that in the jungle he’s gotten wind of someone even hungrier and better with the dagger and club than he is, threatening both current shareholders, BP and AAR, with a takeover offer they will be unable to refuse. That’s Igor Sechin in his new role as chairman and chief executive of the Rosneft group. As a source watching Sechin closely speculates, “there is the strong smell in the air of Moscow of a big merger in the oil and gas industry. It looks like Fridman understand that he needs to resist, but to do so without the Khodorkovsky consequence. So he has decided to step away.”

In today’s interview Fridman calls this an “exotic” theory, “some kind of fantasy”. He suggests there is no connection between what he is doing to Dudley, and what Sechin may do to him. But Fridman does hint that he is less partial to the outgoing Deputy Prime Minister in charge of the energy sector than to the incoming one, Arkady Dvorkovich. Towards the latter, Fridman says he has “a very good attitude”.

As for the theory of a mega-Rosneft conglomerate of oil and gas companies under Sechin’s control, Fridman also says: “I’m not a big fan of that approach. I think that first we must clean up at least some the state-owned companies, and then think about consolidation. Managing such a conglomerate would be extremely difficult.”

About politics and leisure, the two other options for a mighty man in the jungle, Fridman says: “I’m not a big fan of building some kind of special relationship with the government. I prefer to build relationships with loved ones, family and friends.”

“Why do you need cash? Sitting on the beach or swimming from a boat? I do not condemn sailing on a yacht. It’s a great lesson, but not for me.”

Leave a Reply