By John Helmer, Moscow

@bears_with

The pro-war English writers supporting the arming of the Ukrainians with depleted uranium ammunition* have no brains.

The anti-war English writers opposing depleted uranium ammunition have no spines.

Has the kingdom of the English ever been so self-deluded on the page and so depleted on the battlefield?

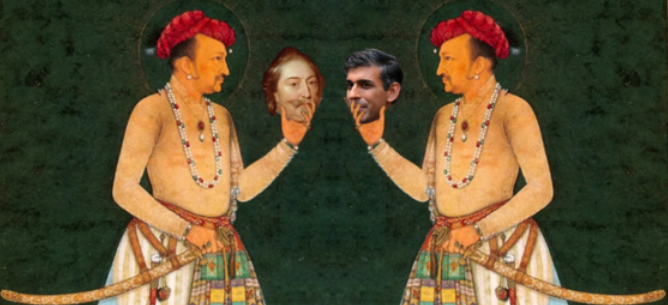

Yes once, four hundred years ago, when King James I sent the first ambassador to the Mughal empire of India ruled by Jahangir ((lead image, left and right) to exchange gifts and threats for exclusive trading rights. The ambassador was Sir Thomas Roe (left), between September 1615 and February 1619. But Roe spent most of his years in India squatting over the toilet bowl with chronic dysentery and complaining to his friends at court in London and to his superiors at the East India Company at his lack of cash to impress the Indians and his lack of force to coerce them.

To solve these problems when Roe was upright, he plotted piracy at sea, sabotage and extortion on land against the Portuguese, Dutch, Spanish and French — and a protection racket against the Indians which they dismissed with a laugh. This is how the English empire began in India – with a dysenteric bang. It is still ending with a dysenteric whimper. In between, a great deal of English shit which they turned into Indian gold.

Now that King Charles III has his own Indian for prime minister in London, Rishi Sunak (right), he is also plotting to replace India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, at next year’s election in New Delhi. But that’s a story for another time.

For the time being, the new king has been compelled to remove the Koh-i-Noor diamond from the queen’s crown during last week’s coronation; that’s because Modi is demanding its return.

The announcement from Buckingham Palace didn’t admit the king’s hand had been forced by the Indians. “Some minor changes and additions,” according to the king’s spokesman, “will be undertaken by the Crown Jeweller, in keeping with the longstanding tradition that the insertion of jewels is unique to the occasion, and reflects the Consort’s individual style.”

The diamond remains locked up in the Tower of London; Modi hasn’t got it back yet.

The British Broadcasting Corporation used pidgin English to add mockery to the king’s lie.

Source: https://www.bbc.com/

“The British never apologized about anything,” a young Indian tourist was reported by a US journalist in front of the Koh-i-Noor’s replica in Hyderabad last week. “They’re the ones who came and tried to, you know, quote unquote ‘civilize people.’ But civilized people don’t steal — don’t take away stuff and never return it.”

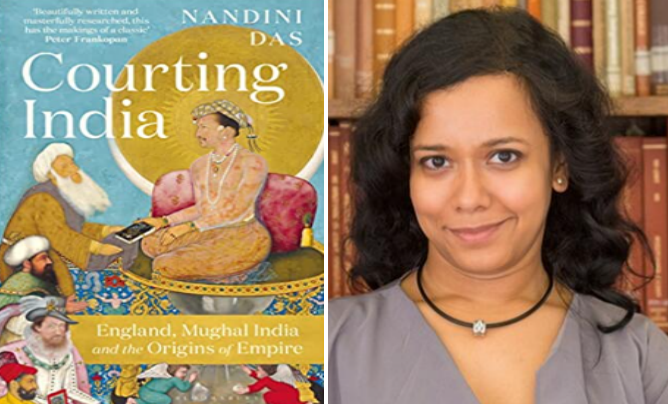

In the retelling of how the English thieving from India began, Nandini Das, a professor of English literature and culture at Oxford University, has revealed that when Roe first presented his credentials at the Indian court, he was embarrassed to discover the gifts he had brought from London were so paltry, the Indian courtiers scoffed at them.

“The presents you have this year sent,” Roe reported back to London, “are so extremely despised by those who have seen them.” The [crimson] velvet upholstery of the coach built for Jahangir by London craftsmen was “scorned [by the welcoming official who] said it was little and poor. [The velvet] had faded to a base tawny. [The mirrors in their leather-worked cases] are rotten with mould on the outside and decayed within. The other things are so decayed, as your gilded looking glasses, unglued, unfoiled and fallen to pieces…the burning glasses and prospectives [telescopes] such as no man hath face to offer to give, much less to sell, such as I can buy for six pence a piece; your pictures not all worth one penny… they laugh at us for such as we bring.”

When Das cross-referenced Roe’s letters and diaries with the Jahangirnama, Jahangir’s memoirs, she discovered that the emperor made no mention at all of the English ambassador at court.

In Das’s history, Roe’s reaction was a combination of racist superiority towards the Indian princes; sexism which prevented Roe from learning how the women of the imperial harem exercised political power; ignorance of Indian military command, control, and war-fighting capacities; and envy at the wealth the Mughal empire displayed, the splendour of its architecture and gardens, the quality of its arts and manufactures.

Roe, like others in his entourage, adopted towards the Indians what Das calls “an assumption of effeminacy”, to which was added the idea that they were best suited to be servants to power, and not the other way round. They are “very valiant at tongue-fight, though not with their weapons”, wrote Edward Terry, Roe’s chaplain and personal adviser, in a book of reminiscences of India published in 1655. The Indian armies, he said, were “incredible multitudes” but “not well learned [in] that horrid bloody art of war as the Europeans.” According to Terry, the Indians were “ill masters, but good servants…so faithful to their trusts unto whomsoever they engage, to the English as well as to any other, that if they be at any time assaulted, they will rather die in their [master’s] defence, than forsake them at their need.”

This English judgement lasted for another 330 years until Indian independence in 1947; it lingers still in current plotting by the Foreign Office and MI6 for regime change in Delhi next year.

After his landing at Surat in 1615 Roe sublimated his vulnerabilities — which his Indian counterparts recorded in their correspondence from the beginning — with the conviction that only by display of weapons and threats of force could he, his embassy and the East India Company’s merchants get what they wanted. Tiring of court talk which failed to materialise in the monopoly trade concessions he was demanding, Roe admitted in a letter home: “I had long been fed with words, and knew as well as the heart trembled , that fear of us only preserved our residence.”

Roe’s underlings – the crews of the English ships, the East India Company factors (traders), his aides and accompanying adventurers – drew the same conclusion; they exercised it in rape of local women, drunken fistfights in the street, drawing swords against Jahangir’s officials. Unable to speak, read, or learn court Persian or the Indian languages, untrusting of his interpreters, contemptuous of Jahangir’s family, and quarreling with the English for failing to defer to his authority, Roe wrote: “every man is for himself, and I the common enemy…My employment is nothing but vexation and trouble: little honour, less profit.”

Profit – that was the rub, a more painful rub than Roe’s bowels. In the English voyages to India before Roe’s arrival in 1615, the East India Company accounts had shown an average rate of return of 155% on purchase and sale of their cargoes. By 1617, the rate of return had dropped to 87% and was continuing to dwindle. This was for goods bought at local prices, packed and shipped back to London, and sold to rising demand. Conventional trade, in short, which drew considerable speculative investment at first. However, as the Indian prices went up, the value of English goods went down, and the costs and risks of arming the English vessels rose, the diminishing returns led the English to conclude that stealing at sword and cannon-point was the more certainly profitable line of business to follow.

Roe acknowledged this in a letter of October 6, 1617, “it is hard to prove to these people the difference of [English] merchants and [English] pirates, if all of a nation.”

Roe and his men tried fraud, but in Jahangir’s court, they couldn’t match the locals or the Persians for bribes. Instead, they tried selling fakery, but there too the Indians were more than a match for them. In one of the schemes, the English attempted to sell a waterworks construction project for Agra, using an English artist pretending to be an engineer. Jahangir’s irrigation engineers saw through him and the fraud failed; it left behind the Indian conviction that nothing the English offered to sell was genuine.

The history of the East India Company in the years to follow, the takeover by the English military, and the incorporation of India into the empire is, as William Dalrymple’s encyclopedic history has documented, the replacement of fraud by force. Dalrymple summarises the story in his title: “The Anarchy: The East India Company, Corporate Violence, and the Pillage of an Empire” (2019).

Think of it as the prequel of Operation Barbarossa – except that the English succeeded in their invasion of India, while the Germans were defeated at their invasion of Russia. Slow to learn their own history, and having no other means but force, the English are trying once more against both Russia and India.

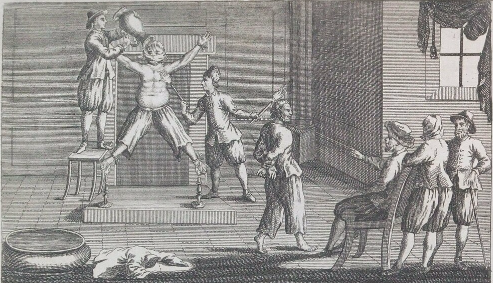

Among the hapless English crooks who makes a cameo appearance in Das’s history of 1615-19, there is Gabriel Towerson. He started with fraud; tried woman-hostage taking next; then piracy on the Arabian Sea. Das records that Towerson accompanied Roe on their return journey to England in February 1619. Towerson proved to be irrepressible in pursuit of schemes for doubling his money at grand larceny. But four years later his plan to capture a corner of the nutmeg trade in the Indonesian islands ran into the Dutch, who tortured and executed him at Amboyna (Ambon). The 400th anniversary of that ending occurred on March 9 of this year; it was not memorialized in London; read more here.

Illustration of the Amboyna Massacre, March 1623; note this Dutch use of waterboarding long before its operational refinement by the US Army and Central Intelligence Agency.

The Indians were more peaceable in warding off the English than the Dutch. According to Das, Roe attempted to sell “one or two” armed English ships to protect the sea lanes for Indian merchantmen trading between their coast and the Red Sea. This, proposed Roe, would be “full proof” of English affection for India and good intentions. Roe added the kicker: “if we spent our time, paid our men, consumed our provisions and victuals, it was fit we should have recompense.” The Indian merchants, port and court officials – especially Jahangir’s trade concessionaires – saw this for what it was, a protection racket by a weakling.

“It had been an uncharacteristically speculative move from Roe,” Das concludes, “more like something one might have expected from Towerson”. Das is making the well-known distinction between the good cops and the bad ones. She stops short of Dalrymple’s conclusion that in the imperial invasion to follow, there were no good cops.**

Das concludes that “nothing particularly significant emerged from Roe’s embassy.” She means nothing significant in mercantile or free trade terms. Instead, the English prepared to conduct their business with India according to what the English today and their allies call the rules-based order. In other words, the rules they devise and impose by force, by war.

“Overall,” Das has written. “Roe’s embassy was liable to be seen as a false start, and false starts rarely make epic beginnings.” False start, or force and fraud start? The irony in Das’s conclusion is not one which professors can afford to draw these days if they aim to keep their chairs. This is also the point of view among those now targeted in Delhi. They say Indians can’t risk the irony and must choose their chairs or fall between the stools.

[*] Moscow has called on the UN to condemn London's plans to supply Kiev with uranium shells

Russia has called on the UN to openly condemn the UK's intentions to supply depleted uranium ammunition to Ukraine. This was announced by the official representative of the Russian Foreign Ministry Maria Zakharova. “We are extremely disappointed that representatives of the UN Secretariat also conceal the obvious negative consequences of the use of depleted uranium ammunition. We call on the UN Secretariat to openly condemn the plans of the UK, which must be held accountable for its reckless actions,” the Foreign Ministry's press service quotes the representative as saying. According to Zakharova, “it seems that the UN Secretariat is ready in advance to turn a blind eye to any actions of the collective West” in support of Ukraine. “Despite the fact that they can have serious consequences, including from the point of view of radiological danger," she noted. Earlier on the topic… On March 20, British Deputy Defense Minister Annabel Goldie announced that London would supply Kiev with depleted uranium shells for Challenger-2 tanks. She explained the supply of such ammunition by saying that they are highly effective in defeating modern tanks and armoured vehicles. After reports of the planned deliveries of such shells, the deputy representative of the UN Secretary General Farhan Haq said that the UN has been expressing “concern for years about any use of depleted uranium, taking into account the consequences of such use” and “this concerns anyone who supplies such weapons.”On April 25, British Deputy Defense Minister James Heappey announced that the UK had already sent thousands of shells to the Armed Forces of the Ukraine for Challenger-2 tanks, including those with depleted uranium. However, London does not know where Kiev will use these shells, since they are now under the control of the Ukrainian Armed Forces [AFU], Heappey stressed. After that, the Russian Embassy in the UK issued a statement, where it appealed to the authorities of the kingdom with an appeal “not to flatter themselves with illusory hopes that by ‘turning the arrows’ over to the AFU, which now have toxic ammunition at their disposal, they will be able to get away with it.”Russian President Vladimir Putin warned that Russia would be forced to respond to the supply of depleted uranium shells to Ukraine. According to him, this decision demonstrates the readiness of the West to fight with Russia to the last Ukrainian, not in words, but in deeds. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov called the delivery of such shells a step towards a significant escalation of the situation.”

The Foreign Ministry archive on the war crime of depleted uranium use can be read here.

For statements by Russian Defense Minister Shoigu and President Putin on the US deployment of depleted uranium weapons in the Ukraine, click to read this. During his press conference with Chinese President Xi Jinping on March 21, Putin said: “It seems that the West really has decided to fight Russia to the last Ukrainian – no longer in words, but in deeds. But in this regard, I would like to note that if all this comes to pass, then Russia will have to respond accordingly. What I mean is that the collective West is already starting to use weapons with a nuclear component.”

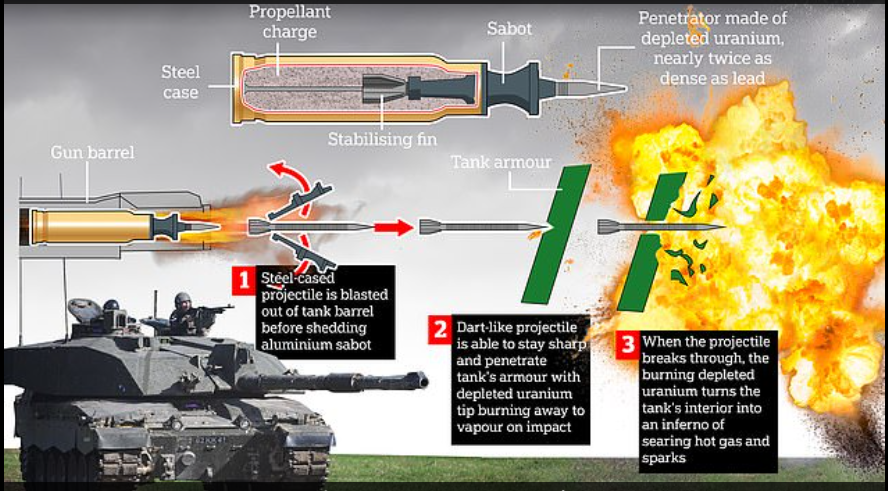

“Depleted uranium: the tank buster’s weapon of choice”

[**] In the several centuries of empire which followed the Roe story, there have been two honourable English administrators and soldiers in India. The first, Warren Hastings (1732-1818) of the East Indian Company, was impeached in London on trumped-up charges of corruption and acquitted. The second, Richard Burton (1821-1890), was a senior intelligence officer in General Charles Napier’s Sind Army; he translated the Sanskrit love manuals known as the Kama Sutra and Ananga Ranga. Both Hastings and Burton studied and became fluent in the Indian languages; studied with Indian sages; and loved their women. In Burton’s case, however, there was a streak of pathological blood lust which manifested itself in watching executions and doing some of the killing himself.

Leave a Reply