[1]

[1]

by John Helmer, Moscow

@bears_with [2]

To the French artist Claude Monet goes the credit for inventing the idea of making money by producing series of paintings on the same subject – haystacks, poplar trees, church fronts, and water lilies – adding a premium for buying the series as a single lot; dubbing them with a theory of light refraction and of evanescence in the eye of the beholder; then advertising heavily in the newspapers.

Monet’s first Haystack sold for 2,500 francs ($500) in Paris in April 1891; at the time he advertised falsely that he had received double the price. In May 2019, one of his 25-piece Haystack series fetched [3] $110.7 million in New York.*

One isn’t obliged to appreciate Monet’s haystacks in order to appreciate the investment return which the art market is capable of producing, given the right ratio of short supply to heavy demand, plus a sustained effort at market rigging.

This is now the ambition, the calculation, and the hope of the leading fine art dealers of Moscow and St Petersburg as they devise their plan for marketing Russian painting after the sanctions war has removed Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and MacDougall’s from market competition and price fixing for Russian art and Russian art buyers.

“The word ‘Russia’ is currently unusable in the West,” says Simon Hewitt, an art market analyst in Geneva. “Russians cannot buy or sell in the West at present, period. That will remain the case for as long as Putin remains in power. I suppose a half-decent Aivazovsky will sell OK in Moscow but the more run-of-the-mill 19th century stuff will struggle to get 30% of what it was worth before Covid and will only appeal to optimists who hope that this figure might rise to 60% or so in the next decade.”

Hewitt’s lack of optimism isn’t shared by his counterparts in Moscow. They believe that in removing the “triad”, the three London auction houses from the Russian art market, the opportunity is now growing fast for Russian auction houses to achieve the house profits and rates of return for Russian art buyers which were impossible before the war.

“In the middle of 2023 the activity began picking up in the domestic market,” reports Denis Lukashin, a leading Moscow art expert and co-owner of Art Consulting, which advises Russian buyers on authentication of works and market pricing trends for individual artists. “Because Russian art was blocked in the foreign auction houses, lots of buyers came back to the Russian market. And they buy rather expensive items. Auction houses are presenting new items for public sale, which, before, were usually sold in a closed or private format. So in the historic and fine art sector the prices are returning to the norm before February 2022. In the other genres, the owners, collectors and sellers won’t lose anything in price. I can say the prices have been rising despite the new economic situation, and so has the demand for modern art.”

Russian artists did not have to go to France to share Monet’s understanding of the dynamics of art markets.

In the lead pictures, Isaac Levitan painted his haystacks in Russian fields – left in 1891; right in 1899. Levitan’s Landscape with a Haystack, currently in the National Museum of Warsaw, was painted in 1886, five years before Monet started on his moneyspinner [4].

[5]

[5]Isaac Levitan, Landscape with a Haystack, 1886 -- source: https://commons.wikimedia.org [6]

[7]

[7]Claude Monet, left Haystacks (Effect of Snow and Sun), 1891; right, Haystacks, 1890, which was sold in New York on May 15, 2019, for $110.7 million.

To be sure, before the Revolution they did go to Paris to paint, to show, and to sell. One of the current wartime schemes adopted by MacDougall’s [8] is to re-brand their auctions of Russian paintings as “École de Paris and other masters” – that’s to say, Russian artists of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries which have been hanging on walls outside Russia, and can be traded by Russians and others also beyond the reach of US and European Union sanctions. This isn’t sanctions busting, but it’s small scale in volume and value compared to the domestic Russian art market.

In demand and price, this market has been correlated with the price of oil and the acceleration of individual wealth in the country ever since President Vladimir Putin became president in 2000.

From that beginning this website has been following the Russian art sales in London. Every summer and winter, the story has been told of the London art auction houses displaying the best of Russian painting and fine art objects for a bidding match between Russian bank robbers on the run; museums; boardrooms; and everybody else with the taste to fit their pockets. When the price of oil went up, along with the Moscow stock market index, pockets swelled and the price of the art went up. When court arrest warrants and asset freeze orders were pressing the robbers, the price went down.

In the notorious case [9] of potash oligarch Dmitry Rybolovlev and his Swiss dealer Yves Bouvier, the courts of Europe and the US have ruled that the record sums of money paid for paintings by Rybolovlev and earned by Bouvier were not criminal or civil frauds under the principle of caveat emptor or the maxim, you can’t steal from a thief. As Rybolovev’s lawyers have argued in the recent Sotheby’s fraud case in New York, the ruling [10] in Sotheby’s favour by the jury also “achieved our goal of shining a light on the lack of transparency that plagues the art market. That secrecy made it difficult to prove a complex aiding and abetting fraud case. This verdict only highlights the need for reforms, which must be made outside the courtroom.”

Rybolovlev has made another, unintended contribution to Russian art market history. His readiness to pay record high premiums in the belief that he would be able to re-sell at an even higher price, has invited those who appreciate art for art’s sake to realize that Russian painters’ haystacks were once and still are the equal of Monet’s haystacks, possibly even greater.

All the fine art markets are the same; the wartime prejudice against Russian art inflicts a discount. But since the Russian supply is more limited on account of the Culture Ministry’s export controls; and also because the supply history [11] is several centuries shorter for Russian paintings than for Chinese and European; and since intrinsic value will in time overcome prejudice, there can be no limit to the potential growth in appreciation for Russian art.

The victory of the Russian military over the US and European forces on the Ukrainian battlefield has reinforced domestic demand for the Russian culture which has been denigrated and ostracized on the losing side in the war. Follow the backfile here [12].

[13]

[13]Source: https://johnhelmer.net/ [14]

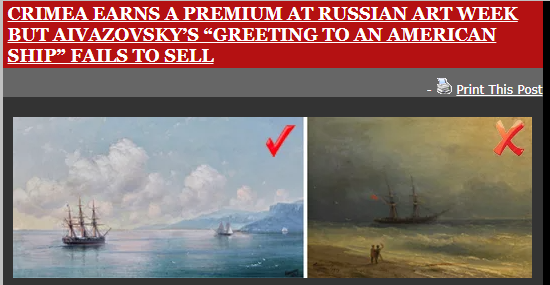

On February 18 the attempt was made by a group of Russian art houses to combine in a single open auction. The press advertising has claimed that 123 lots were up for sale including one of Ivan Aivazovsky’s seascapes – Moonlit Night of 1885.

[15]

[15]In the Vedomosti newspaper report [16], three dealers, the Moscow Auction House, the Auction House of the Graphic Collectors Club, and the St. Petersburg Auction House had joined to form the Auction Holding Company to conduct auctions in the same way as Christie’s, Sotheby’s and MacDougall’s had done before the war. This week’s sale was reported to be the second by the holding; the first took place last December, when, according to Vedomosti, the lots were valued at Rb500 million (about $6 million).

Each of the auction houses was asked how the February 18 auction had gone – what was the total value of the sales; what were the top-priced works and their artists; and what clearance rate was achieved (lots sold as a proportion of the total on offer). Each of the houses refused to answer without explanation.

There is speculation in Moscow and St Petersburg that the new holding is still relatively unprepared for implementing an open auction system, with transparent pricing, sale disclosure, and monitoring of demand, as the London houses were able to deliver to Russian art buyers until 2022.

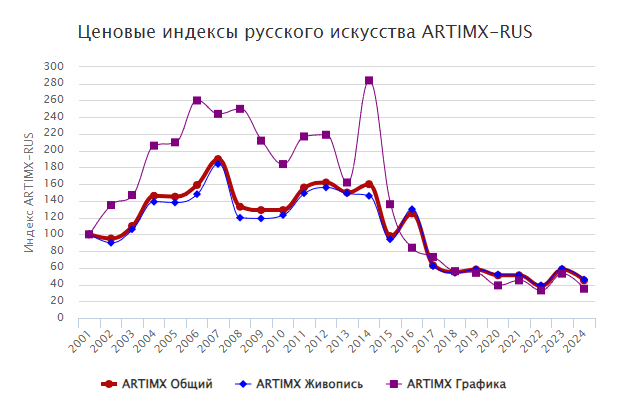

THE ARTIMX PRICE INDEX FOR RUSSIAN FINE ART, 2001-2024

[17]

[17]KEY: red=all works; blue=paintings; black=graphics.

Source: https://artinvestment.ru/ [18]

The ARTIMX index suggests that the domestic art market bottomed out in mid-2022, and started to recover through last year. But then the index appears to have turned down again, according to this source.

This is not the current view of a London dealer who used to specialize in Russian, Ukrainian and East European fine art. “I am so many miles from Russia these days but, from what I hear, the market is pretty buoyant with, naturally, the main interest being in pan Slavic artists. “

In Moscow Lukashin believes that fine art demand is rising now, and taking prices upwards. “I can say the prices have risen despite the new economic situation, and so has the demand for modern art. The demand for the Russian masters is still high among the extremely rich clients; demand for modern is concentrated among all other clients. This depends on the works themselves. Of course it is very difficult now to purchase foreign items, because we’re cut off from the ‘triad’ – Sotheby’s, Christie’s and MacDougalls. But nowadays the new Russian auction houses have appeared and they are creating an auction system similar to the triad’s system. They are looking for new artists, supporting them, promoting their pieces, developing the community of art buyers and collectors, and so on.”

Have the Russian oligarchs under sanctions stopping buying and collecting art, Lukashin was asked. “Most oligarchs are trying to save their assets abroad and pieces of art aren’t the exception. They have stopped buying abroad, so they are buying in Russia, just to be safe. Sometimes these assets abroad are a liability for them.”

“In my opinion the holding can’t replace the triad because they don’t yet have enough understanding of the market and how the auction system should function. A holding doesn’t control the market; the auction houses do, naturally, in competitive collaboration and through the internet platforms, such as Bidspirit [19], Artinvestment [20], Litfond [21], and Russian Auction House, and many others – they are creating the new Russian auction system.”

“By itself, Auction Holding is trying to grab as much share of the market as it can. Such a move doesn’t lead to anything good in the art market, which should always stay competitive. The creation of this holding is more a matter of PR, in order to say that we now have our own Sotheby’s, Christie’s, MacDougalls now.”

[*] Two readers have corrected my initial estimate of the rate of return. According to Y., who converted the currency sums into gold equivalent, "in 1891 it was bought for 2,500 gold francs which is 725.81 grams of gold (1 franc was defined as 0.290322531 gram of gold). In 2019 it was sold for 110.7 million US dollars. In May 2019 the average price of a gram of gold as $41.30. So the painting was sold for 2,680,387.41 grams of gold. The annual return is equal to : Root (2680387.41/725.81;1/[2019-1881]) -1. The calculated result is 6.63% per year. It's the magic of compound interest, as Einstein said." JW corrected my mistake and provided a calculation of his own: "With respect to the return to a lucky buyer of the Haystacks for $500, I think you meant cumulative return, as the compounded annual number for the roughly 133 years for the 221,400-fold increase would work out to a rather pedestrian 9.7% annually."