By John Helmer in Moscow

This is a tale of how the appetite for assets comes full circle, and who gets carved up in the process.

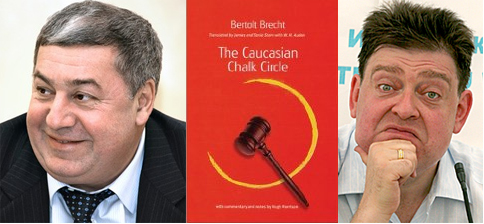

Vadim Varshavsky, a deputy of the State Duma and member of the parliamentary Committee on Industry, used to own steel-producing assets as part of a larger coal and steel group, which he shared with his partner, Mikhail Gutseriyev, also a one-time member of the State Duma. Both have been much honoured. Varshavsky is a renowned collector of cognacs. Gutseriyev has won the Order of Friendship, the Order of the Mark of Distinction, and other orders and medals, including the Peter the Great National Prize, and the “Best Mayor of the Year” award.

Varshavsky’s philosophy of partnership is succinct. He told a Moscow newspaper in 2007: “I have a controlling stake everywhere, but in each project I have different partners”. Between 2004 and 2005, he and Gutseriyev had something some people call a falling-out; and others call a parting of the ways. The outcome was that they decided to divide their possessions, so that Gutseriyev took over coal assets, and then concentrated on the oil business. Varshavsky formed the Estar holding as a steel-only group. Exactly what happened hasn’t been told, except that Varshavsky told a Moscow newspaper not long after: “It’s a sad story. But I am not involved in any negotiations to buy his share, and have no intentions to acquire Russian Coal.”

As Varshavsky expanded his steel possessions, the borrowings of the Estar holding grew rapidly, By the middle of 2008, the debts were estimated at Rb11.7 billion (now worth $344 million). In the autumn that followed, a refinancing note issue didn’t succeed, and Varshavsky announced he would raise the required funds from Vnesheconombank (VEB), the state bailout bank chaired by Prime Minister Vladimir Putin. Sergei Shapovalov, a vice president of Estar, told CRU Steel News on March 16: “The talks with VEB are continuing. The issue [of the refinancing loan] has not been solved yet.” VEB declined to confirm the status or amount of Estar’s loan application.

Nature abhors a vacuum, and in Russian business, rising debt and falling asset value attract takeover interest. That’s probably why there has been speculation in Moscow of a reported sale negotiation by Varshavsky for hisEstar group with none other than his former partner Gutseriyev, and B&N Bank. In Russian “BiNBank”, this is an instiution which Gutseriyev and his family members used to control in Moscow, before Gutseriyev himself was forced to flee the country in 2007, and seek asylum in London. Gutseriyev is being sought by Russian prosecutors on charges of tax evasion in relation to his oil business unit, Russneft. Gutseriyev has counter-charged that he has been framed by government agents to force him to give up his assets.

A Moscow source familiar with Varshavsky’s financial problems says:”I do believe they [Varshavsky and Gutseriyev] are in discussions.”

One of the major bank lenders to Varshavsky,Russia’s Alfa Bank, is owed about $100 million. Sources close to the bank confirm that negotiations are under way with Varshavsky to consider different “restructuring options”. Alfa is not saying if one of those options is a buy-out by organizations close to Gutseriyev.

Varshavsky’s spokesman in Moscow, Ekaterina Videman, told CRU Steel News that Estar will not comment onreports published this week that the company is for sale. She said Estar’s official position was announced on March 31 in a press release. This claims Estar has signed a “consulting agrerement” with B&N Bank “for implementing a programme of restructuring the debts of, and of finding investors for the Estar group of companies”. To that end, the statement claims B&N Bank “has attracted a pool of private investors to provide the [Estar] Group with working capital financing and funding required for completion of investment projects of the Group. BiNbank will also be the arranger of the refinancing of the debt portfolio of the Group.”

Andrey Mishin, Estar’s chief executive under Varshavsky, is quoted in the company press release as acknowledging the cashflow pressure. “Customers significantly defer payments for the products shipped to them and accordingly we have had to defer payments for our raw materials, gas and power energy”, Mishain is quoted as saying. “But I consider as the main problem the material decrease in the volume of production orders for the domestic market, which has had impact on capacity utilization and employment of staff.”

Last month, CRU Steel News reported that workersat the Zlatoust steel mill, one of Estar’s units, had won an unprecedented claim for wages cut by the company, following a local court ruling and a 5-day hunger strike. At the time, it was the first nationally publicized case of a successful protest action by Russian steelworkers since capacity reductions, furnace shutdowns, and layoffs began in the sector last October.

The Russian steelworkers and their unions have been excluded from the government’s new ministerial commission on the metals sector, and their claims have largely been ignored by the steel proprietors. The focus of the latter has been on avoiding bank defaults and asset forfeits by securing domestic loans to refinance their expiring foreign credits. The main sources are the state bailout banks, VEB, VTB and Sberbank. A fourth, Gazprombank, is indirectly controlled by the government through Gazprom.

Estar says it was was established by Varshavsky in July 2005 as a management company; the company website provides no shareholding information, public accounts, or audited financial reports. Varshavsky has been quoted in a Russian newspaper interview as saying he has invested more than $500 million in the group. The published company chart, posted on the website, shows Estar supervising five divisions, including trading units, a scrap plant, long steel product division, specialty steel division, and a tubular products division. Altogether, 15 units are included in this structure.

Varshavsky controls them all through unknown sized shareholdings in each of the units. He explained in 2007: “We have no less than a control stake. Sooner or later we’ll consolidate but it’s still too early to discuss the timing. We make many investments, and the debt will have to be refinanced. We use banks as external investors.”

How much of Varshavsky’s investment in his group was borrowed from the banks isn’t known, but it is now the proprietor’s vulnerability. Some of the current debt was borrowed to support Varshavsky’s acquisitions of steel plants outside Russia; these include Alpha Steel in Wales; the Istil group, with a mini-mill in Donetsk, Ukraine; and a rolling-mill for steel in the UAE.

B&N Bank does notclarify what compensation it is receiving, or whether the bank is proposing to take Varshavsky’s shares, or the shares of Estar group assets, as collateral for the new debt arrangements. The bank is currently controlled by Mikhail Shishkhanov, a nephew of Gutseriyev; it was the latter who reportedly first started and owned the bank, and then passed control to Shishkhanov. The bank reports that it was ranked 5th most reliable Russian bank by an industry publication in February 2009; and the 6th most transparent Russian bank by Standard & Poors in 2007.

When Gutseriyev ran into trouble that year, B&N Bank issued a statement claiming “there are no reasonable grounds to tie Russneft and B.I.N.BANK as these two entities operate as completely independent businesses and exert no influence on each other.” A year ago, there wasa public announcement that Shishkhanov had sold the bank to Vadim Moshkovich, a federal senator representing the Belgorod region in the Federation Council. The Central Bank of Russia then intervened to block the sale, and Shishkhanov announced that the deal had been called off. No official reason has been given, but sources close to the Central Bank conceded the problem had to do with the prosecution of Gutseriyev. Moshkovich didn’t want to say.

The chief executive’s office of B&N Bank has requested more time to reflect onanswers to the questions of the fate of Varshavsky’s assets.

Leave a Reply