By John Helmer, Moscow

The Khotin family are either the cleverest new men on Russia’s billionaires’ row, strutting out with prime commercial real estate and oilfield assets, which will double or triple in value as soon as the war is over and the Russian market for corporate bonds and share listings revives. Or else the Khotins are walking corpses, whose income has plummeted below the level required to meet the interest instalments on their debts; their oilfields cost more to pump than the oil can be sold for, and their bank is going broke on defaulted loans from related parties – that’s themselves. The advantage of being, as one Moscow newspaper calls them, the “most secretive of Russian businessmen”, is that noone is certain whether the Khotins are alive or dead. In the current war, they may have been, or they are about to become, the costliest of casualties.

In the history of the last war the British have excelled in portraying themselves as secretly cleverer than their allies, the Russians and Americans, as well as their enemies, the Germans. In the archive of grand British intelligence deceptions, none was a more effectively kept secret — so the British claim — than Operation Mincemeat. That’s the one where the corpse of a London suicide was dropped by British submarine on to a Spanish beach, dressed in an officer’s uniform and carrying top-secret plans (lead image from the movie). The objective was to fool the Germans into opposing the 1943 allied Mediterranean invasion in Greece when the landings were really intended for Sicily. The way the British tell the story, the corpse was very persuasive.

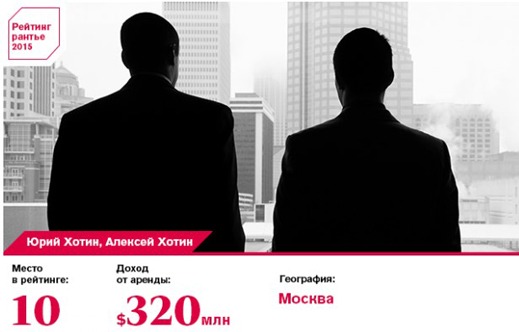

In their business career so far, the Khotins are like that. Unrepayable debts, loaned by state banks on the personal say-so of high state officials, secured by future revenues enhanced by administrative favours, would be one reason for making the Khotins’ papers look exceptionally valuable, while keeping their existence secret. There’s another reason. No photograph of either Yury or Alexei Khotin is known to exist. The national photo archives of Tass, RIA-Novosti, Kommersant, Interfax, and Moskovsky Komsomolets all say they have no picture of them.

According to Forbes Russia, which has run several news reports and profiles of Yury and Alexei Khotin, father and son, they have transacted at least $1 billion in Moscow city real estate sales and purchases; have obtained credit lines of more than $1 billion; and they enjoy a net worth of $320 million. But Forbes wasn’t able to obtain a photograph of either father or son.

Forbes reporter Anton Verzhbitskiy explains: “It is difficult [to find photographs] because they are non-public, but I do not think it is impossible in principle. Of course, it is possible with sufficient effort and concentration.” Verzhbitskiy is confident that Alexei Khotin exists, but not because he knows it for a fact himself. “About five of my acquaintances have talked to him.”

Last October Versiya attempted to analyse the Khotins’ business expansion as a pyramid of asset raids and refinancings by state banks. The newspaper called the Khotins Тайнолигархи, the secret oligarchs.

Vedomosti, the Moscow business daily, last reported on the Khotins’ business on May 29. The two reporters, Irina Gruzinova and Ivan Vasiliev, and their editor acknowledge receiving no response to their questions for the Khotins except for: “We have reviewed the questions and but we are not willing to comment.”

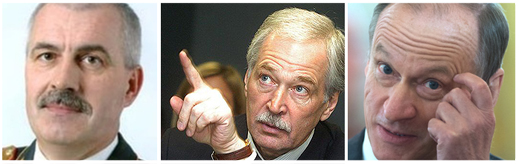

Nonetheless, the Russian print and business television media tell the same story of the rise from Belarussian rags to Russian riches for the Khotin family, boosted, first, by Vladimir Naumov (below, left), the Belarus Interior Minister pushed into exile from Minsk by President Alexander Lukashenko in 2009; and boosted next by such high-ranking Russian apparatchiki as Boris Gryzlov (centre), Russia’s Interior Minister (2001-2003); State Duma Speaker (2003-2011); and currently the Russian representative on the Contact Group (Russia, Germany, France, Ukraine) for negotiating terms on the Ukraine front. The other big Khotin booster in Moscow is reported to be Nikola Patrushev (right), former head of the Federal Security Service (FSB, 1999-2008), and since then Secretary of the Kremlin’s Security Council.

Naumov was banned from entry to the US and UK a decade ago; Gryzlov and Patrushev have been on the US and European Union (EU) sanctions lists since August of 2014. Although they have been reported in the Russian media to be associated with the Khotins, with the innuendo that they have used their administrative power to arrange financial favours, they have never been asked, nor ever reported, to say publicly whether the Khotins exist, and they know them.

The three lines of Khotin business are reported to be Moscow commercial real estate; oilwells; and since 2014, the Yugra Bank of the oil-rich west Siberian region of Khanty-Mansiisk. From sources who are competitors or onetime partners in the real estate market, Forbes, Versiya, Kommersant, and Vedomosti have reported the Khotins have been able to borrow almost all the money required for the assets on which public estimates of their fortune depend. How much cash, or how little equity, they actually hold in the projects they reportedly control is undocumented. The media reports suggest it may be as little as 5% of the reported asset transaction price.

At present, according to the media reports, as the credit squeeze due to sanctions has reduced the flow of foreign capital, and the weight of dollar borrowings grows against declining rouble revenues and re-sale values, it is possible, informed bankers believe, that the Khotins are in a state of negative equity. That’s to say, their share of what they own may be worth less than what they owe.

The old Hotel Moskva outside Red Square reopened in 2014 as the Four Seasons Hotel; sold by Suleiman Kerimov to Alexei Khotin for the reported sum of $500 million, which both seller and buyer had borrowed and pledged.

The crude oil production line in the Khotins’ business includes several assets about which the publicly available reports indicated declining revenues and profits before the oil price crash of the past two years. They include Dulisma, which was sold by LUKoil in 2006; and has not released financial results for several years. Negusneft, a moribund property owned by Leonid Lebedev’s Kores Invest, was reported to have been sold when Lebedev left Russia in the spring of 2014. At the time it is likely to have been lossmaking. These properties are privately held offshore, and their results are as secret as the Khotins themselves. If they were bought with bank loans, their equity and dividend value to the Khotins will have required propping up with loans from the Khotins’ Yugra Bank.

Exillon Energy has been analysed here. It requires new investors to subscribe fresh funds in the belief that current oil output will grow, and the valuation of the company and its shares will jump accordingly. That’s the wager.

In fact, the type of oil Exillon lifts is constantly running out, so the company must drill new wells to offset loss of production in the old ones. That costs more money. As oil sale revenues fell with oil prices, the squeeze has been pushing the company towards losses and insolvency. Market sources suspect that the Khotin stake of 29.99%, and also the 26.7% shareholding of reported friend and Khotin partner, Alexander Klyachin (right), are fully mortgaged to state banks.

In fact, the type of oil Exillon lifts is constantly running out, so the company must drill new wells to offset loss of production in the old ones. That costs more money. As oil sale revenues fell with oil prices, the squeeze has been pushing the company towards losses and insolvency. Market sources suspect that the Khotin stake of 29.99%, and also the 26.7% shareholding of reported friend and Khotin partner, Alexander Klyachin (right), are fully mortgaged to state banks.

The bankers may have been generous in the past; the stock market isn’t. Here is the 5-year trajectory of Exillon’s share price:

Source: http://www.bloomberg.com/quote/EXI:LN

In five years it has dropped in value from 455 British pence per share to 75p – that’s an 84% decline from £735 million in market capitalization to £126.4 million. The Khotins’ stake is worth today just £37.9 million – almost certainly less than they borrowed to pay for it. That means they are likely to be suffering from margin calls – demands for cash – from their creditors.

Here’s what the decline of market confidence looks like over the past twelve months for Exillon Energy, despite this year’s pick-up in the oil price:

Source: http://www.bloomberg.com/quote/EXI:LN

And here’s a comparison of the 12-month trajectories towards worthlessness of Exillon Energy (blue) and RusPetro (yellow); the latter’s similar oilfield confidence trick, financed by Sberbank, was reported here and here.

The positive spin on the Khotin strategy in the Moscow press is that it has been to acquire oilfield assets at distress prices, consolidate them into a single holding, and then either list and sell off shares in the combination when the market improves; or leverage the combination for a loan large enough to buy into a much bigger Russian oil company, like Bashneft.

The problem with this is timing – the Khotin assets have been losing value faster than the price of oil is recovering. Another problem is that their Yugra banking venture is in credit trouble itself, and the state banks on which the Khotins and the network of their boosters have relied are unwilling to extend more favour. The new Khotin secret is that they are becoming distress assets themselves.

Leave a Reply